Nine years ago today, Kosovo’s Declaration of Independence marked the most important moment in the country’s modern history. Kosovar women and men, old and young impatiently waited in front of televisions in their homes, in bars and in town squares in order to witness the historic moment; after the Declaration was made, many took to the streets to celebrate with families, friends and strangers until the early hours of the following day.

It was a moment that had been widely eagerly awaited since the end of the war in 1999, when hundreds of thousands of Kosovar refugees and internally displaced people returned home to reclaim their hopes and lives after a decade of tumult.

Many children born during the war were given names that expressed the struggles and hopes of their parents during the bloody struggle, as many other children were given names that expressed hope, optimism and sentimentality after the withdrawal of Serbian forces controlled by Slobodan Milosevic. Today, many of them are frustrated and angry at older generations and Kosovar institutions for failing to provide them with a better environment in which to grow up.

As eight- and nine-year-olds when Kosovo declared independence, they may have been too young to clearly understand the magnitude of the event, but they will soon have the right to vote for the first time and to have their voices heard in shaping the country’s future.

To mark Kosovo’s 9th birthday, K2.0 spoke to nine 17- and 18-year-olds about nine topics linked to the country’s independence.

What does your name mean? Is there any history behind it?

Arta Hasani (Mitrovica, 17): Something golden. Precious. Like the golden age that started after the war.

Yll Brezhnica (Mitrovica, 17): I was born right after the war, but my name is not related to Kosovo’s liberation. My brother was born after the declaration of independence, and his name is Bardh (White). It is a symbol of this country’s fortune, as it gained independence. My family is thinking about having another child when Kosovo joins the EU, so as to connect it with these three important dates for our country and our family.

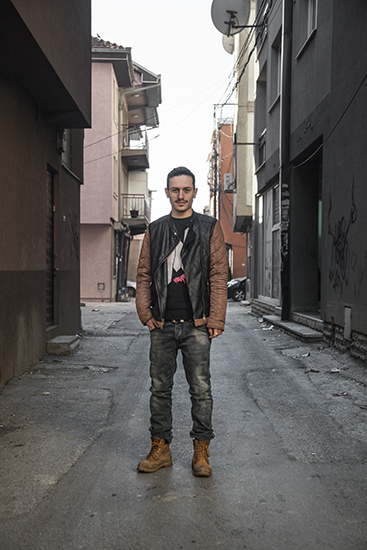

Zoga Hasani (Ferizaj, 18). Photo: Majlinda Hoxha / K2.0.

Zoga Hasani (Ferizaj, 18): The reason why my name is Zoga (Bird) is because my family loved freedom just as birds like to fly free.

Krenare Sejdiu (Podujevo, 18): I was given the name Krenare (Proud) probably because my grandmother and grandfather were patriots. My grandmother was the sister of a martyr. So my grandmother, maybe out of pride, felt that it was fitting to give me this name. Besides the reason about her brother, I think she also wanted Kosovo to be proud.

Jovan Maslar (North Mitrovica, 17): My family left Prishtina before the family’s [traditional Serbian Orthodox celebration] slava St. Jovan, and to remember this they gave me the name Jovan.

What are your memories of Kosovo’s Declaration of Independence in 2008?

Arta: I remember celebrating all day with my family. From the morning we were in front of the TV waiting anxiously for the Declaration of Independence to be read. It was one of the days in which I was most joyful as a child. It was the day that made me proud to be a Kosovar. I didn’t understand much of what was happening at first, but then my parents explained that this day marks the passage from a dark age to a brighter one, and so this touched me. I must have held the flag for about a week straight, at home and in the city. I never put it down.

Yll: We watched TV up until the declaration itself was made. It was a joyful day, albeit in Mitrovica the atmosphere wasn’t as jolly. We went out to town with the car and celebrated until late, despite the fact that we were just kids. As a curious kid I remember asking what independence meant. They simply told me that it means that “it’s going to be alright.” We celebrated with the flag of Albania, because Kosovo flags went on sale later. Today Kosovo has its flag and we must support it.

Zoga: The only moment I remember is when the flag was raised here in Ferizaj city center. It was surprising in a way because I always thought the flag would have the eagle on it, or at least something nice, but then we saw that it was the Kosovo map with stars. Although it was a good idea, it was very unexpected for us. We celebrated while waiting for the declaration. It was a very cold day but it still didn’t stop us from celebrating at home and in the city. I was very young, and it was not a good idea for me to be outside because of the weather, but it was hard to stay indoors from all the joy.

Noli Lluka (Peja, 18). Photo: Majlinda Hoxha / K2.0.

Noli Lluka (Peja, 18): There was a concert in the center of the city of Peja and people were really elated and shared drinks with each other. That day nobody asked us why we were hanging out all the time away from home. I remember many people who were emotional and were crying and for me as a nine-year-old, those faces that were crying became embedded in my memory.

Aurela Tahiri (Podujevo, 18): I remember independence as something that my parents spoke about. They said that now we’d be free and independent, although I think that we’ve never been completely free, because what we have is not independence. I don’t know. It doesn’t feel like it.

Sallvahe Shaqiri (Vushtrri, 17): I heard on the news [that independence was being declared]. We were afraid, thinking that something would happen.

Krenare: A few days before the declaration, the media spoke about it but I personally also felt fear. I don’t know, we were afraid that the war would start again, seeing that the Serbs opposed our independence. Maybe since our families were occupied by them, they were even more afraid, and hearing them speak about it caused that fear to be transmitted to us. The municipality had organized a party that day. There was music and dancing, and I also went out to celebrate.

Genc Maloku (Vushtrri, 18): I remember independence day. I dressed up in national attire. We went out holding flags and celebrating. It was joyful. I remember watching the news, when it was announced that independence would be declared. We went out in Vushtrri to Adem Jashari square, by the park. There were many flags. We celebrated, and then we went to a restaurant to feast with our relatives.

Who is Kosovo’s best ambassador?

Arta: Majlinda Kelmendi by a mile. She makes me proud, and has represented us with dignity. She has also helped convince others to recognize us as a country. To know that there is a Kosovo somewhere, that it exists and it has many talented people.

Arta Hasani (Mitrovica, 17). Photo: Majlinda Hoxha / K2.0.

Yll: Eshref Durmishi, the producer of the film “Shok.” He has simply made us so proud, with the film participating in the Oscars and everything. Majlinda Kelmendi as well.

Noli: Majlinda Kelmendi. She is the only one to win gold medals for the country and we in Peja, and the whole of Kosovo is proud of her. Although the state is not helping her much with finances she still continues to make us proud.

Sallvahe: Majlinda Kelmendi. Rita Ora for music.

Krenare: People in the field of culture like Rita Ora, or athletes like Majlinda Kelmendi. I think politicians are not representing Kosovo with dignity. I don’t think anyone in politics matches up to Majlinda or Rita.

Jovan: I don’t have any names but I have a reason. The reason is that every person that does something good for people in Kosovo should be happy just for the fact that they helped someone or did a great job for a whole country here. We have such people but we don’t know them because they just help. We don’t have public figures that do good things for Kosovo, I mean the whole of Kosovo, even if they do it they do it to get money. Even small act of kindness here are huge for the whole of Kosovo.

Genc: Athletes, I’d say. Majlinda Kelmendi, Milot Rashica, Nora Gjakova. Through sports we’ve become members of the international community. We’ve become better known through sports than through politics. There are not many skilled politicians within the young generation.

Jovan Maslar (North Mitrovica, 17). Photo: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0.

Who is Kosovo’s most dominant figure?

Arta: Politicians are the people who dominate usually, but in my eyes I don’t see any positive domination. Hashim Thaci [is dominant], albeit not in a positive way.

Zoga: I think the most dominant figures are Rita Ora and Dua Lipa. They are dominating our country and other countries with their originality and their music.

Noli: Behxhet Pacolli. He did a lot for Kosovo. Many countries recognized Kosovo because of him.

Aurela: Albin Kurti, because everyone has tried to claim power, but no-one has done anything for us. Everything is getting worse. Whereas Albin Kurti has never had this opportunity. If we give it to him, maybe he can do more than the others.

Genc: I think the most skilled politician, which doesn’t necessarily mean that he is a good person, is Hashim Thaci, because he wins elections. Albin Kurti on the other hand has a better outlook. He has managed to make a considerable part of the population his. I personally like Behgjet Pacolli as well. He is sincere, and I don’t think he would steal as the others are doing.

Sallvahe Shaqiri (Vushtrri, 17). Photo: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0.

What does the word ‘state’ symbolize for you?

Arta: A place in which you belong and that you are tied to, no matter where you go. That place gives you feelings and has a lot of value for you. And even if you go to another place with better opportunities, you cannot find that same feeling elsewhere.

Yll: For me a state is a territory that has rules that must be implemented by all citizens of all countries, but especially of Kosovo.

Zoga: A state is about well-being. When people are happy to be there, and are offered all they need.

Noli: As I was born in Peja, we immediately went as refugees to Ulqin after the war started. My family could barely find doctors when I was born as most of the people had left the country. It was so difficult. And eight years after the war, we gained independence. The state for me has a lot of meaning, bearing in mind how much we sacrificed to have it from the Serbian regime. Now that we are free, the state means freedom for me.

Sallvahe: Something good. A place where you can live, work and go out. A place with good schools and jobs.

Krenare: Everything related to governance. A proper state must be governed properly. Kosovo is a small country and has easy development opportunities, but unfortunately our youth want to leave Kosovo, because it is not a proper, functioning state. I’ve been thinking about what to study, and every field that I’ve considered, there’s always been this voice inside me, telling me that there are no prospects in Kosovo in those fields. Now I’m thinking about moving abroad. It’s deplorable: In our country you cannot have a normal life, or an average life, let alone a better one.

Yll Brezhnica (Mitrovica, 17). Photo: Majlinda Hoxha / K2.0.

What does gaining the right to vote mean to you?

Arta: The right to vote means I get to choose. I get to pick the person that I think is worthy of doing the job. I wait for my influence to be felt. No matter whether the person I vote for wins or not.

Yll: My vote can be the vote that changes a lot. Although it is just a piece of paper, it can be powerful when grouped together with other pieces of paper. All books start being written from one page, and then go on to become really voluminous. So my vote can make a change in my community.

Aurela: The right to vote is leaving your life in the state’s hands. I don’t see how voting is reasonable. I don’t trust anyone in politics enough to leave my life in their hands. I’m not sure whether I’m going to vote or not.

Krenare: I don’t know. I don’t think I have anyone to vote for. For example, I like Albin Kurti as an individual, but his party Vetevendosje, I feel doesn’t represent what he stands for as an individual.

Jovan: It means that I can make a change. Changes are brought about through votes. From the Serbian side, everyone says ‘Kosovo is Serbia’ and gets everyone’s vote in the north; in the south side everyone is playing with Kosovo’s independence and building Kosovo and they get the votes. But what are they doing in reality? Nothing! So even though I now have the right to vote, I don’t know who to vote for.

Genc: I think we’re not yet mature enough to vote. As a whole, we are immature. I know that I am one of the most mature people, and there are others that do not even think when it comes to voting. This causes a lot of damage. [Politicians] are gaining the votes of the weak. [Voting] can bring more qualified people to power. That is why there must be a certain level of awareness among people. Change must come through people initially, then through votes. We must be mature as individuals, and only then will the leaders be strong too.

How does being a ‘Kosovar’ make you feel?

Arta: I feel quite proud that I belong to this people and am very thankful for belonging to this country. I am thankful that I was born and raised here.

Krenare Sejdiu (Podujevo, 18). Photo: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0.

Yll: I feel a bit excluded. I feel isolated for sure. But also excluded from politics.

Zoga: As a Kosovar I am very proud to belong to this country, be it because of the nature, or even the challenges that we face in education — I still feel pride when speaking about Kosovo. On the other hand, visa restrictions are a huge barrier for us, especially for people like me who study art. There are many concerts that I want to attend but it’s problematic because I can’t travel to Germany or Vienna to see concerts. But I hope that ultimately it will change.

Krenare: I haven’t traveled abroad because I haven’t had a visa, so I haven’t had the chance to tell someone that I’m a Kosovar. But I think if such a situation would come up, most people that I would tell that to would probably think that we are a poor, miserable state.

Genc: We are not free like other people are to travel abroad, to get an education abroad. For example, I want to study abroad, but I face many barriers such as high costs, visas, many applications, knowing the native language of the destination country, even though you might never actually need it. There are many problems that are related to Kosovo’s lack of full freedom, its exclusion from EU and its visa restrictions. I feel emptiness, because we’re still a very young and incomplete country. We are not full of history, as Kosovars.

Aurela: I feel very good, but I think people still relate us to our past, to the war.

Jovan: Indifferent.

Where do you see Kosovo when it turns 18? What progress do you hope to see?

Arta: In nine years I see Kosovo as a much more developed country, compared to today; in the fields of education, economy, health — fields of great importance. The education field in particular, because without having a developed education sector, Kosovo cannot be developed in other fields. These are processes that take a lot of time, but if they kick off now, we can achieve what we want to in nine years.

Aurela Tahiri (Podujevo, 18). Photo: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0.

Yll: In nine years I want to see Kosovo offering many opportunities for its youth and communities, because as we know they aren’t very well integrated. They should have opportunities for inclusion in every aspect of citizenship. I also want to see more progress in education and architecture.

Zoga: I think in nine years we’ll have good opportunities for our students, for children, for the elderly. I think we’ll have a better life for the elderly, and more health care for them, as we lack it today.

Aurela: I want the youth to be able to find jobs after they graduate, not just wander around the streets all day.

Krenare: I want to see an 18-year-old Kosovo without poverty. After that, I want to see more jobs, and better governance. Also I think we need more spaces for youth activities.

Jovan: To cross this bridge, and think about it as a bridge that connects two parts and not something that separates them. I went to a restaurant [in south Mitrovica] once, but you still have that question: “What if something happens?” You say to yourself: “Let’s be quiet so they don’t hear we are speaking Serbian.” You know we can cross the bridge but we need to cross the bridge in our minds. I would like to one day be able to cross the bridge, meet each other and say: “Hey buddy, friend, how are you?” Many things happened in the past, it is not that we should forget about them, but we should finally sit down and address those things — it happened, it is in the past. We should say: “We did this to you, and you did this to us and the ones who did this should be in jail.” You have so many cases on the Albanian side where people are missing, people were killed and no one is in jail for that. I think the only way to stand together is to address these cases; to tell people that we are talking about those issues and not just trying to forget them or sweeping them aside.

Genc: At that time I’ll be 26. I’d like to see Kosovo as a member of all international organizations. I would like to see more opportunities. I’d like to see crime reduced, as it can never be completely eradicated. I want to see equal opportunities. I want to see a better political elite, full of intellectuals. I don’t want to see big constructions, as they come with time. I think changes in culture and education would influence all other aspects, therefore they are the most important.

Genc Maloku (Vushtrri, 18). Photo: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0

Is the glass half full or half empty?

Arta: I wholeheartedly believe that it is full. I see my country with optimism.

Yll: In many aspects for Kosovo the glass if full, but also empty. It is half empty because if there is no water, the glass is worthy as well, and it needs filling. You fill it by developing the youth, by giving them opportunities.

Zoga: I see it as half full.

Noli: I see it as a half full.

Sallvahe: Half empty.

Aurela: Both, because one half is always empty, and the other always full.

Krenare: Empty.

Jovan: The glass for me will be always half full, even if it is just a third full. Because I think that no matter how much the situation here is awful, or seems that way, there will always be a sort of hope left and that is enough for things to change.

Genc: Half full. I don’t see the empty part. I am an optimist by nature. And an idealist. I’m also a realist.