The Albanian diaspora is as diverse as Albanians themselves, each story framed by the individual histories of families, towns, villages and hardship. This story is mine: my family’s, my friends’ and, in a small part, the story of Kosovo.

The political struggle of the 1980s and ’90s and the war of 1999 are the major markers of memory for Albanian Kosovars. They are the stories that the children of political refugees, asylum seekers and the expelled hear, witness, and repeat; for many of us, our parents’ stories are what make us Albanian, just as much as the language, the Albanian community organizations and the annual visits to the homeland.

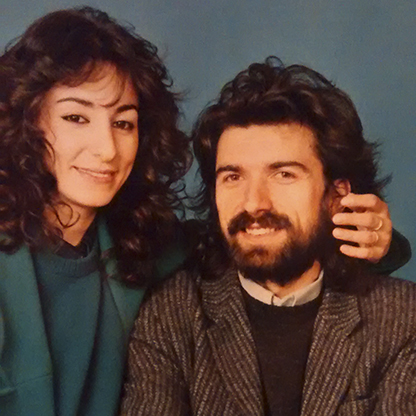

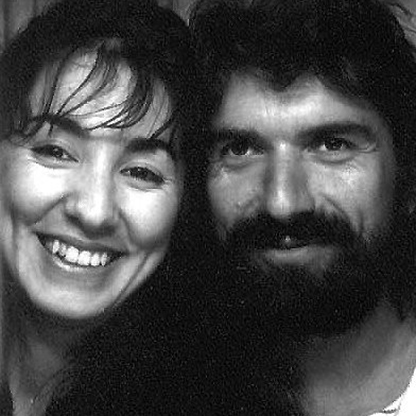

My parents lost their jobs in the waves of firings of Albanians that occurred in Kosovo after its autonomous status was revoked. My mother sang for the choir of the Philharmonic Orchestra, my father was an animator and trick cameraman at the Radio Television of Prishtina. I like to look at photos of them before they emigrated — young, hopeful and in love.

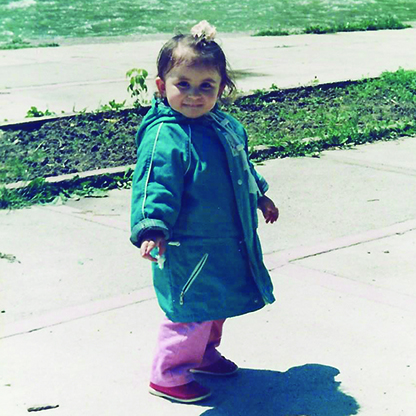

I was about 5 years old when my parents went to the U.S. — without me. They didn’t want their children to learn Albanian in a basement, under the surveillance of police officers happy to brutalize anyone unlucky enough not to be Serbian.

While my father repaired roofs and my mother sold coffee and donuts in Connecticut, I stayed with my grandparents in Macedonia. I remember talking to my mother on the phone and not understanding the situation, asking if I could see her just for a few minutes. I didn’t know that she was crying on the other end of the line.

Getting on a plane, rejoining my parents and learning a new, strange language is a blank spot in my memory. The decade that followed was a merry-go-round of school, my sister’s birth and watching my parents work, work, work and work — until the war.

My friends, the other ones born late enough to remember the war — late enough to have seen it and known it — tell stories of immigration that share the same pain of starting from scratch and watching war brew from afar.

Academics say that diasporas become radicalized when the homeland is in danger, and I think it’s true, especially after witnessing our parents’ fear and anger, watching them glued to the television, glued to the phone, glued to slow Internet connections, smoking, yelling, arguing, telling stories of death that seemed too awful to be true in our suburban Western homes. That’s how we learned about war, when we saw the same shell-shocked refugees that flooded the Macedonian border before our eyes in Canada, Germany, the U.S., Switzerland, France — in any country that would have them. That was when Kosovo became real to me, at least.

The postwar adrenaline release came much later. Our parents stopped sending 3 percent of their income to the cause. We went back to Kosovo (my parents as prodigal sons), and my sister and I returned “home” to a place we’d never really known as home.

A late bloomer, I learned about the Albanian Rebirth much later, under the instruction of the same teachers who used to teach in school-homes (in the years that led up to the war, as well as during the conflict, the education of Kosovar Albanians often took place in hastily repurposed homes). The national poet, Naim Frasheri, had spent a greater portion of his life away from Albania, dreaming about a brightly burning candle, about a sublime Albanian-ness that would pull us out of darkness. Nearly all the Great Poets lived or had studied abroad, I learned, and they paradoxically defined Albanian-ness for the rest of us.

The promise of the candle that burned brightly was the secret religion of Albanians in Kosovo, following them to the first settlements in Germany and Switzerland, even as their passports declared them Yugoslavs. The demonstrations of the ’80s and ’90s in Kosovo reignited the old promise of living and breathing free as an Albanian. The old diaspora of the ’50s and ’60s was shaken up by the flood of their politicized compatriots who had arrived as asylum seekers on the shores of Europe. The communities of Albanians abroad, for a span of time, opened their wallets, chanted at protests, demanded meetings with important men in suits and picked up guns to fight as liberators.

But the end of the war also meant a long, slow sigh, and as the dust settled, we got a chance to really see one another. It turns out Albanians can lie, can cheat and can generally act completely contrary to how the Great Poets said men must be. People can be as damaged as a country. We went back to Canada, to start over — this time voluntarily.

I was happy to use the subway, to go to university and to have a big, North American city to wander in. People called me “Hannah” instead of Hana, and I didn’t correct them. I annoyed my mother to no end by dating a non-Albanian, and then obsessed over the Facebook profiles of nearly every eligible Albanian male within a 100-mile radius. I went to school, and then more school, and finally got a job in a cubicle.

I looked down on young Albanians in Toronto who settled before the age of 25, but I also envied them. I went out with Canadian friends and learned how to be both Albanian and Canadian at the same time. Work wasn’t awful, but it wasn’t exciting, either. My work, my partying, my little dreams made no difference to anyone. I felt (rightly or wrongly) rootless, and guilty for my silly existence while the real work of rebuilding a country was happening an ocean away.

This is where the story gets complicated, because second- and third-generation immigrants are eternally a step apart from the homeland, and their interpretations of home form a messy spectrum. Albulena lived life according to her parents’ rules, and was the first of the group to get married after university and start working in a bank. If Petrit could have, I think he would have written up official divorce papers between himself and the Albanian nation — that’s how derisive he became of everything Albanian. Merita was the easiest to talk to, and she seemed to have struck that mysterious balance between loving Kosovo without being delusional and being a good Albanian daughter — while also pursuing a life of her own.

Each one was different, and each figured out their own way to deal with familial duty and the fact of their inescapable bond to Kosovo. Some find comfort in the Albanian Flag Day celebrations, the independence concerts in February, the picnics, the nights of Albanian culture and music, and the never-ending weddings. Others find them stifling, and are at constant war with their sense of belonging (or lack thereof) to the community.

I feel the most affinity with those who returned. It’s a lie to say that young idealism is dead, at least among my generation of the diaspora. I moved back, and so did Merita, as well as others whom I met along the way. There are no more big causes for us here in Kosovo — there is no threat of destruction and there is no outside enemy. It’s only us, now, and our own flaws as a people. Our desire to sacrifice, to contribute, to help rebuild (a desire based on the ideals of our parents and our childhood) — well, I think it is good and healthy for that desire to be met with disillusionment. Disillusionment means change, and our friends who never left Kosovo know about the need for change better than we ever will.

Our parents wanted to raise the next generation of Albanians abroad, but they could not have predicted what would become of us. Some of them will continue to send money back home, but not as much as before. Some of us will cling to the Albanian flag like a talisman, and some of us will renounce it altogether. Some of us will never go back, and some of us will continue to return, university diplomas in hand. Most of us will be trying to find that middle ground, to be like a candle burning brightly in the night, consumed with blind love.