“And he turned to me and said, ‘General Clark,’ he said, ‘We know how to handle these murderers, these rapists, these criminals.’ He said, ‘We’ve done this before.’ I said, ‘Well, when?’ He said, ‘In Drenica in 1946.’ And I said, ‘What did you do?’ He said, ‘We killed them.’ He said, ‘We killed them all.’”

– Testimony of NATO General Wesley Clark on Dec. 15, 2003 about a conversation he had had with Slobodan Milosevic in October 1998.

***

Over the past two and a half decades, the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) has had its hands full with “big fish” such as Slobodan Milosevic, Radovan Karadzic and Vojislav Seselj, while at the same time inviting a lot of controversy with its trials and judgments. Having indicted 161 individuals and sentenced 90 of them, it is now on the verge of closing its doors after 24 years.

In the last year of its existence, and during its very final case, the tribunal itself became a “crime scene” when a commander of the Croatian Defense Council in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and war criminal, Slobodan Praljak died after drinking poison in the courtroom, seconds after his judgment was read. “Praljak is not a criminal. I reject your verdict,” were his last words in the court.

In order to address the performance of the ICTY and to understand the structure of what started as a temporary tribunal and ended up as a “crime scene,” we have to go back to its roots, to where it all began.

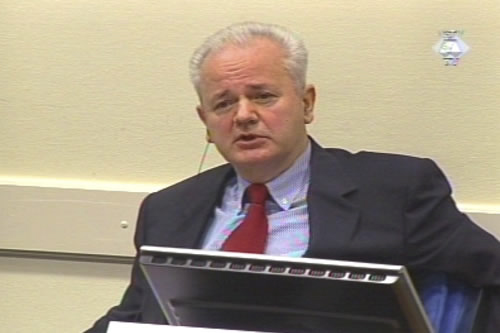

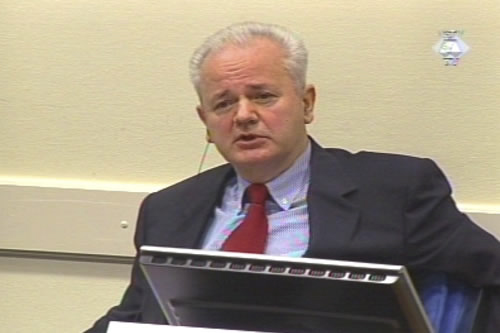

Slobodan Milosevic (IT-02-54)

INDICTED: “Kosovo” — Initial: May 24, 1999 / Operational: October 29, 2001

“Croatia” — Initial: October 8, 2001 / Operational: July 28, 2004

“Bosnia and Herzegovina” — Initial: November 22, 2001 / Operational: November 22, 2002

CHARGES: Across the Kosovo, Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina indictments, Milosevic was charged with crimes against humanity (in all three indictments), violations of the laws or customs of war (in all three), grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions (in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina), and Genocide (in Bosnia and Herzegovina).

The specific charges in total were: genocide; complicity in genocide; deportation; murder; persecutions on political, racial or religious grounds; inhumane acts — forcible transfer; extermination; imprisonment; torture; wilful killing; unlawful confinement; wilfully causing great suffering; unlawful deportation or transfer; extensive destruction and appropriation of property, not justified by military necessity and carried out unlawfully and wantonly; cruel treatment; plunder of public or private property; attacks on civilians; destruction or wilful damage done to historic monuments and institutions dedicated to education or religion; unlawful attacks on civilian objects.

VERDICT: Proceedings terminated on March 14, 2006 due to his death.

(Source: ICTY)

The ICTY was formally established in May 1993 by the United Nations Security Council, through Resolution 827; it became the first war crimes court established by the UN, as well as the first international war crimes tribunal since the Tokyo and Nuremberg tribunals in the aftermath of World War II. Since then, it has seen 10,800 trial days and heard 4,600 witnesses.

The establishment of the ICTY came as a result of the brutal conflicts that built up and took place throughout former Yugoslav states in the ’80s and ’90s, while Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union were witnessing the collapse of communist systems and a resurgence of nationalism.

“Former Yugoslavia” refers to the territory that, up until Slovenia and Croatia declared their independence on June 25, 1991, was known as the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY), and included six republics: Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia (plus the regions of Kosovo and Vojvodina) and Slovenia.

According to its statute, the ICTY has had the authority to prosecute persons responsible for specific crimes committed in the territory of the “Former Yugoslavia” from January 1991 onward; its jurisdiction has only ever been over individual persons and never over political parties, or army units or any other legal subjects.

These specific crimes fall into four categories: Grave breaches of the 1949 Geneva Conventions, violations of the laws or customs of war, genocide, and crimes against humanity.

As a tribunal it has had concurrent jurisdiction over serious violations of international humanitarian law committed in former Yugoslav states, along with the respective national courts. However, the ICTY has always been able to claim primacy and take over national investigations and proceedings at any stage of the trial and has been able to refer its cases to the national authorities.

With the ICTY having initially been enacted as a temporary tribunal, when by 2003 it was operating at full capacity the need for a different strategy arose. As such, the tribunal’s judges devised a plan that later became known as “the completion strategy,” the purpose of which was to ensure that the ICTY concluded its mission “successfully.” What “successfully” meant was merely finishing up in a timely way and in coordination with the domestic legal systems.

Ratko Mladic (IT-09-92)

INDICTED: Initial: July 25, 1995 / Operational: Dec. 16, 2011

CHARGES: Genocide (killing members of the group, causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group); Crimes against humanity (persecutions, extermination, murder, deportation, inhumane acts — forcible transfer); Violations of the laws or customs of war (murder, terror, unlawful attacks on civilians, taking of hostages)

VERDICT: Life imprisonment (issued Nov. 22, 2017)

(Source: ICTY)

The plan was endorsed by the UN Security Council in resolutions 1503 and 1534 and foresaw the completion of investigations by the end of 2004, completion of first instance trials by the end of 2008 and completion of all of its work in 2010. But the late arrests of some fugitives, the complexity of the cases and the lack of collaboration from certain states made it impossible for the court to meet its own deadlines, and only the completion of investigations took place on time.

Legal firsts

After the establishment of the ICTY in 1993, the first indictment was issued on November 7, 1994 against Dragan Nikolic, the commander of a detention camp in Bosnia and Herzegovina; the indictment was issued for crimes committed against non-Serb civilians. The tribunal would continue seeking suspects until July 2011, when Goran Hadzic’s arrest meant the search for fugitives came to an end as all 161 individuals indicted by the tribunal had been accounted for.

The search for the “big fish” began not long after the tribunal’s founding. On November 15, 1995 Republika Srpska political and military leaders Radovan Karadzic and Ratko Mladic were indicted for genocide. More than a decade after the indictment issued against Karadzic, he would be transferred into the custody of the Tribunal in July 2008 and subsequently charged with genocide and various other crimes committed against civilians in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Twenty-three years after the indictment, and eight years after his arrest, Karadzic would finally be sentenced to 40 years in prison in March 2016, thereby holding him responsible and guilty for the majority of the counts in the indictment.

Radovan Karadzic. Photo courtesy of the ICTY.

Following the arrest of Karadzic, in May 2011 Ratko Mladic would finally be captured after 16 years of circumventing justice. Mladic would also be charged with genocide and various crimes against humanity as well as violations of the laws or customs of war for the siege of Sarajevo and other events in municipalities across Bosnia and Herzegovina. He would ultimately be convicted, in November 2017, of genocide, crimes against humanity and violations of the laws or customs of war; he was sentenced to life imprisonment.

Arguably the biggest breakthrough for the ICTY came on May 24, 1999 with the indictment of Slobodan Milosevic, the first indictment for a sitting head of state issued by an international court. At the time, Milosevic had neither surrendered nor was he arrested but a change in the political scene following the September 2000 presidential elections in Serbia and mass street protests in October 2000 led to Milosevic begin overthrown from power.

Upon the ICTY’s insistence that the new authorities in Belgrade should transfer Milosevic into its custody to stand trial, in 2001 — two years after Milosevic had been indicted — Serbian Prime Minister Zoran Djindjic authorized Milosevic’s transfer to The Hague. Nevertheless, the proceedings against Milosevic would have to be terminated before a judgement was reached due to his unexpected death on March 11, 2006.

In the meantime, in August 2001, the tribunal had made its first conviction for genocide. The conviction was against an officer officer from the Army of Republika Srpska named Radislav Krstic, who was specifically convicted for taking active part in the massacre of Srebrenica; future rulings would also confirm Srebrenica to have been a genocide.

Radovan Karadzic (IT-95-5/18)

INDICTED: Initial: July 25, 1995 / Operational: Oct. 19, 2009

CHARGES: Genocide (killing members of the group, causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group); Crimes against humanity (persecutions, extermination, murder, deportation, inhumane acts — forcible transfer); Violations of the laws or customs of war (murder, terror, unlawful attacks on civilians, taking of hostages).

VERDICT: 40 years imprisonment (issued March 24, 2016).

(Source: ICTY)

It took 13 years for the tribunal to hand down the first life sentence. In November 2006, the Appeals Chamber found Stanislav Galic, commander of the Sarajevo Romanija Corps in the Bosnian Serb army, guilty of bringing together a campaign of explosive attacks in Sarajevo between 1992 and 1994.

The second life sentence was handed down in July 2009, against Milan Lukic, who was convicted for the murder of more than 130 Bosnian Muslim civilians in Visegrad in 1992. Soon after the Lukic case, in April of the same year, the third life imprisonment sentence was given, this time to Zdravko Tolimir, the former assistant commander and chief of intelligence and security of the main staff of the Army of Republika Srpska. Tolimir was sentenced for genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes committed in 1995 in Srebrenica and Zepa.

Some of the largest trials to be held at the tribunal were in its final years. The case against Popovic et al., also known as the largest ever ICTY trial, came to an end in January 2015, when five out of seven former high ranking Army of Republika Srpska and police officials were convicted upon appeal of genocide and other crimes committed in 1995 in Srebrenica and Zepa.

The final trials to be held in the ICTY came to an end on November 29, 2017, with the Prlic et al. case against Jadranko Prlic, Bruno Stojic, Slobodan Praljak, Milivoj Petkovic, Valentin Coric and Berislav Pusic; the tribunal gave its appeals judgment affirming the sentences imposed by the Trial Chamber, which had sentenced Prlic to 25 years in prison, Stojic, Praljak and Petkovic to 20 years each, and Coric and Pusic to 16 and 10 years respectively. The accused were convicted of crimes against humanity, violations of the laws or customs of war and grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions.

Kosovo cases

It was not until June 1999 that Kosovo came into the picture for the ICTY and became a part of its operations. The UN, as well as France, Canada, the UK and Switzerland, signed agreements to provide temporary and urgent expert assistance in the investigations conducted by the office of the prosecutor in Kosovo on a gratis basis.

Although Slobodan Milosevic was also charged with crimes committed in Croatia and Bosnia, for Kosovo alone he had a long list of indictments. His charges included the forced deportation of approximately 800,000 Kosovar Albanian civilians and the murder of hundreds of Kosovar Albanian civilians — men, women and children — which occurred in a widespread or systematic manner throughout Kosovo. Furthermore, sexual assaults carried out by forces of the FRY and Serbia against Kosovar Albanians, in particular women, constituted a good part of the indictment.

Slobodan Milosevic. Photo courtesy of the ICTY.

In addition to charges dealing directly with people’s lives, Milosevic was also charged with a systematic campaign of destruction of property owned by Kosovar Albanian civilians, accomplished by the widespread shelling of towns and villages, and the burning and destruction of property, including homes, farms, businesses, cultural monuments and religious sites. As a result of these orchestrated actions, villages, towns, and entire regions were rendered uninhabitable for Kosovar Albanians. When he died in March 2006, the Trial Chamber immediately terminated the proceedings, thereby leaving one of the biggest and most important cases that the ICTY dealt with without a judgment.

The first judgment for war crimes committed during the war in Kosovo was made in November 2005, against Fatmir Limaj, Isak Musliu and Haradin Bala, who were members of the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA). They had ultimately been charged with crimes committed in 1998 in Llapushnik detention camp in Kosovo. Both Fatmir Limaj and Isak Musliu were found not guilty, while Haradin Bala was sentenced to 13 years in prison; he was granted early release in 2012.

In the same year that the Limaj et al. case came to an end, three other members of the KLA in Kosovo were indicted. The initial indictment against Ramush Haradinaj, Idriz Balaj and Lahi Brahimaj was confirmed on March 4, 2005 and made public six days later. They were charged with persecution, cruel treatment, murder and rape, although it was not until January 2007 that the Office of the Prosecutor finally submitted and confirmed an amended indictment, due to errors in the original submission.

The trial of Haradinaj et al. would first end in 2008 when Brahimaj was convicted, while Haradinaj and Balaj were found not guilty and released; a partial re-trial would be ordered in 2010, before all three of them were acquitted in 2012.

“Prijedor” Dusko Tadic (IT-94-1)

The first ever international war crimes trial with charges of sexual violence against men.

INDICTED: Initial: Feb. 13, 1995 / Operational: December 14, 1995

CHARGES: Crimes against humanity (persecutions on political, racial or religious grounds, rape, murder, inhumane acts); Grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions (wilful killing, torture or inhuman treatment, wilfully causing great suffering or serious injury to body or health); Violations of the laws or customs of war (cruel treatment, murder).

VERDICT: 20 years imprisonment (issued Jan. 26, 2000)

(Source: ICTY)

In 2006 came the operational indictment in the Sainovic et al. case that included Nikola Sainovic, Dragoljub Ojdanic, Nebojsa Pavkovic, Vladimir Lazarevic, Sreten Lukic and Milan Milutinovic. The accused were charged with participation in a joint criminal enterprise aimed at modifying the ethnic balance in Kosovo and ensuring continued control by the Serbian Authorities. As explicitly stated in the indictment, the plan was to be executed by criminal means, including deportations, murders, forcible transfers and persecutions of Kosovar Albanians. At the end of the trial in 2014, the sentences were: 18 years in prison for Sainovic, 22 years for Pavkovic, 20 years for Lukic, 15 years for Ojdanic and 14 years for Lazarevic, while Milutinovic was acquitted.

Lastly, Vlastimir Dordevic — who was an assistant minister of the Serbian Ministry of Internal Affairs (MUP) and chief of the public security department (RJB) of the MUP and responsible for all units and personnel of the RJB in Serbia — was indicted in 2008 with deportation, other inhumane acts (forcible transfer), murder and persecutions on political, racial and religious grounds, as well as murder as a part of violations of the laws or customs of war. He was convicted of all the charges in 2014 and sentenced to 18 years in prison.

Moving forward

As the tribunal closes its doors on December 31, the focus of attention now moves elsewhere as the Mechanism for International Criminal Tribunals (MICT) comes into sight.

The MICT was created by the UN Security Council as a “temporary structure” in December 2010 to maintain the legacy of both the ICTY and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR). It started to operate in July 2013 in The Hague, assuming a number of ICTY functions, and now that the ICTY has come to an end it will continue to deal with re-trials and appeals.

As a mechanism it won’t take any new cases but will take over to finish the appeals that have been left unfinished such as Karadzic’s appeal. It will also manage the re-trial of Stanisic and Simatovic, former security service officials from Serbia who are accused of being co-perpetrators in a joint criminal enterprise with an objective of forcibly and permanently removing the majority of non-Serbs form large areas of Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Vojislav Seselj (IT-03-67)

INDICTED: Initial: Feb. 14, 2003 / Operational: Dec. 7, 2007

CHARGES: Crimes against humanity (persecutions on political, racial or religious grounds, deportation, inhumane acts — forcible transfer); Violations of the laws or customs of war (murder, torture and cruel treatment, wanton destruction, destruction or wilful damage done to institutions dedicated to religion or education, plunder of public or private property).

VERDICT: Acquitted (issued March 31, 2016)

(Source: ICTY)

According to some legal experts, the creation of the MICT was not necessary. Former ICTY Judge Wolfgang Schomburg has been one of the vocal voices saying that the ICTY could have incrementally downsized proportionally to the shrinking workload and thereby finished its work on its own. He sees the closure of the ICTY as premature and a result of political reasons.

The closure of the ICTY also coincides with the opening of the Kosovo Specialist Chambers, so at this point it can become a bit unclear as to where one mandate ends and where the other begins.

Looking back at the tribunal’s legacy, alongside the indictments raised and the cases tried, there has been a lot of controversy surrounding the ICTY and its decisions. In 2012 there was outrage in Serbia after convicted Croatian generals Ante Gotovina and Mladen Markac were released by the ICTY on appeal while they were serving jail sentences of 24 and 18 years respectively. The following year a Serbian general, Momcilo Perisic, who was serving 27 years for crimes against humanity, was released on appeal, leaving even some lawyers at The Hague baffled due to the internal contradictions that the ruling contained. There was also outrage in Croatia last year at the acquittal of Serbia’s former Deputy Prime Minister Vojislav Seselj, with the verdict even being labelled as “shameful” by Croatian Prime Minister Tihomir Oreskovic.

The tribunal has faced difficulties with acceptance since the very beginning, with different studies conducted throughout the years making it clear that none of the former Yugoslav states took it lightly when their leaders were indicted. Serbia has been perceived to have had the biggest problems when it comes to collaboration with the ICTY, while Kosovo maintained a very positive approach and stance toward the tribunal until the first indictments for the national “heroes” took place.

Radislac Krstic (IT-98-33)

The first ICTY trial to make a link between rape and ethnic cleansing.

INDICTED: Initial: Nov. 2, 1998 / Operational: Oct. 27, 1999

CHARGES: Genocide (complicity to commit genocide); Crimes against humanity (extermination, murder, persecutions, deportation, inhumane acts — forcible transfer); Violations of the laws or customs of war (employment of poisonous weapons or other weapons calculated to cause unnecessary suffering; wanton destruction of cities, towns or villages, or devastation not justified by military necessity; attack, or bombardment, by whatever means, of undefended towns, villages, dwellings, or buildings; seizure of, destruction or wilful damage done to institutions dedicated to religion, charity and education, the arts and sciences, historic monuments and works of art and science; murder)

VERDICT: 35 years imprisonment (issued April 19, 2004)

(Source: ICTY)

But the tribunal has also achieved significant successes, particularly when it comes to dealing with victims. Throughout the years, the ICTY has had more than 4,600 witnesses on its stands and has considered more than 2.5 million documents. Many victims that had the opportunity to testify in court, had the chance to not only be heard but also to have their pain and experience acknowledged. That is more than any other court has done for the victims of the Yugoslav conflicts.

Eric Stover, a faculty director of the human rights center and adjunct professor of law at UC Berkeley, surveyed the victims of war crimes who had testified at an ICTY trial and his conclusion was that the victims above all drew satisfaction from facing the perpetrators, humiliated, in a courtroom; they valued much less any sentence that was later imposed.

In many ways the ICTY has therefore achieved a milestone in giving voices to the victims, but understandably it is only the selected few that have had the chance to be in front of the court due to the amount of cases that the ICTY handled.

The ICTY has achieved various other milestones, such as establishing facts, holding certain leaders to account and adding to the development of international law.

However, it has missed the opportunity to extend its legacy and experience to the national jurisdictions successfully. It is not too late though for lessons to be learned by national courts, such as those in Kosovo, for example from some elements of the ICTY’s practice of dealing with victims.

It is about the last opportunity for Kosovo’s courts to learn from good practices as they continue to address and try war crimes cases. Because, even though the ICTY’s mandate is over, the search for justice is not.

ICTY in numbers

According to the ICTY’s official figures, it has concluded proceedings for 161 accused, of which 90 were sentenced.

Out of those sentenced:

- 7 are awaiting transfer abroad,

- 16 have been transferred,

- 56 have already served their sentence,

- 9 have died after trial or while serving their sentence,

- 2 are appeal cases that ought to be conducted by MICT.

Of those tried but not sentenced:

- 19 were acquitted,

- 13 have been referred to national jurisdictions

- 37 had their indictments withdrawn or died (out of which 20 indictments were withdrawn, 10 were reported deceased before transfer to the Tribunal and 7 were deceased after transfer to the tribunal).

- 2 will have retrials conducted by MICT

(Source: ICTY)

Feature image: Majlinda Hoxha / K2.0.