During the Siege of Sarajevo, hundreds of thousands of people were bombed and shot at from the surrounding hills, and kept without food, water and electricity for nearly four years. More than 11,000 people died, including 1,100 children. It is the longest siege of any capital city in the history of modern warfare.

How should such an event be commemorated and remembered? One attempt emerged in the years following the siege, when a red resin was added to the craters left by those mortar shells that had killed three or more people after exploding off the concrete. Creating bright red splatters across the city, the makeshift memorials became known as the Sarajevo Roses.

In her book “Sarajevo Roses: Towards the Politics of Remembering,” Azra Junuzović identifies the brains behind the memorials as Nedžad Kurto, a professor of architecture at the University of Sarajevo — though exactly who brought the roses into being remains shrouded in mystery. Junuzović reveals that Kurto wanted to commemorate those who died and suffered without personalizing particular sites.

In his visit to the city in 2014, journalist Peter Korchnak spoke to activists from the Youth Initiative for Human Rights (YIHR), who have taken on the responsibility of reinvigorating the Roses by repainting them in red. The activists showed Korchnak a video in which a middle aged woman expresses her appreciation for the Roses, revealing that she feels they “allow people to be on their own with their thoughts.”

Citizens, journalists and academics have all praised the Sarajevo Roses for their silent power. Photo: Imrana Kapetanović / K2.0.

This sentiment is echoed in a 2013 paper, Silent vs. Rhetorical Memorials: Sarajevo Roses and Commemorative Plaques. Its author, Dr. Mirjana Ristić, describes the Roses as “silent places of memory which allow passers-by to construct their personal versions of memory and multiple narratives about the city’s history.”

Both Korchnak and Ristić contrast the Roses with the memorial plaques that have been erected across the city by the Committee for Marking Historic People and Events of the City of Sarajevo. Korchnak visits a memorial dedicated to the Markale massacre, which states that: “On this spot, on 2/5/1994, Serbian evil-doers killed 67 Sarajevo residents.”

Korchnak criticizes the memorial for “telling people what to think about what happened,” while Ristić describes the entire series of plaques as “conventional rhetorical monuments that articulate a selective version of history based on a particular ethnicity.”

Selective histories across the region

This battle over commemoration and the employment of a selective history has often been fought across the post-Yugoslav states. In May this year, a Dutch human rights organization, Impunity Watch, published a report, which notes that the search for ‘truth’ in the Balkans is being challenged by a unilateral public discourse of denial.

Titled Keeping the Promise: Addressing Impunity in the Western Balkans, the report states that civil society and the media do not have the strength to make the difference in society and the region continues to be a battlefield of conflicting narratives, in which every party claims victimization and blames the others. “History [is] manipulated to tell nationalist narratives that go against any serious attempts to deal with responsibility for the past,” the report says.

Commemoration of events has become a key part of that. In June this year, the Serbian Parliament adopted new legislation to regulate war memorials, according to which monuments can be removed if they are dedicated to an event that is incompatible with the tradition of the ‘liberation wars’ of Serbia. Critics of the law have suggested that it may prevent commemoration of war victims who suffered at the hands of the Serbian state, and that it risks characterizing the wars of the ’90s as wars of ‘liberation.’

Marko Milosavljević from the Youth Initiative for Human Rights’ Belgrade office believes a new law regulating war memorials can only strengthen the state narrative. Photo: Lazara Marinković. / K2.0.

Marko Milosavljević from YIHR in Belgrade says that through this law, “the state narrative is further strengthened.” The activist argues that it is important for Serbian society to oppose these measures not only for the sake of future peace in the region, but also to show respect for the victims of past conflicts.

YIHR have often tried to ensure a place for the victims in the narrative around remembrance. Earlier in the year, during local election campaigns, the Belgrade office requested candidates to commit to the construction of a monument commemorating civilians whose bodies were buried for two years in Batajnica on the outskirts of Belgrade, an ongoing initiative of the organization.

The bodies at Batajnica had been transferred from southern Kosovo in an attempt to cover up a series of massacres, a crime for which former Interior Minister Vlastimir Đorđević was convicted by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia. Since 2001, over 700 bodies have been exhumed from the site, which is currently still used as a training center for the Ministry of the Interior’s Special Terrorism Unit.

In Croatia meanwhile, in August 2010, YIHR activists placed a plaque commemorating all the civilians who left their homes during Operation Storm. According to the Croatian branch of the Helsinki Committee, the military operation on August 4, 1995 left 677 Serb civilians killed, while 200,000 others fled Croatia. Despite this, the anniversary of Operation Storm is often celebrated as a triumph, with military parades regularly held.

On the plaque erected by activists on the 15th anniversary of Operation Storm, it is written: “From the Croatian citizens, who apologize to the victims in absence of an apology from those responsible.”

In July this year, activists from the organization prepared a guide to help politicians apologize for the crimes committed against Serb civilians, suggesting a public apology at the place where the crimes took place that should include a condemnation.

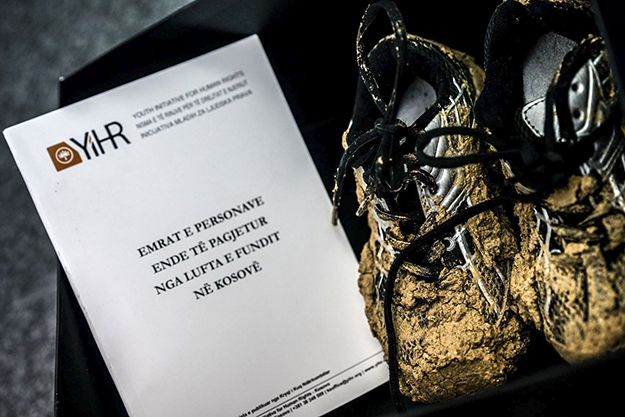

In 2016, the Kosovo branch of YIHR tried to ensure that the missing persons from the Kosovo war did not drop off the political agenda, sending a box of shoes to symbolize the disappeared to then prime minister, Isa Mustafa. Photo by Jetmir Idrizi, courtesy of YIHR Kosovo.

For their part, YIHR Kosovo has tried to ensure that the more than 1,500 missing people from the Kosovo war and its aftermath remain in the public’s memory through symbolic actions, especially on Aug. 30, the International Day of the Disappeared. In 2016, the organization sent a box of shoes symbolising the missing to then Prime Minister Isa Mustafa, alongside a letter saying it was “worried about [official] negligence toward missing persons.”

Marigona Shabiu, the director of YIHR’s Office for Kosovo, says that one of the organization’s main goals is creating a “proper recollection” of the war in Kosovo. For Shabiu, this means “recognition of all civilian victims from all communities, punishing the perpetrators of crimes, and demanding justice.”

To help in this aim, the organization are also making preparations to launch the Virtual Museum of Refugees from the last war in Kosovo. Built online, it will contain both audio and text-based stories, as well as personal photos, all of which will depict the different experiences that Kosovar citizens underwent as refugees.

“This museum will display the journey and personal experiences of citizens as refugees, in order to contribute to the creation of collective memory and symbolic recognition of the suffering of civilians from all ethnic groups during the Kosovo war,” she explains. “The exodus of people during the recent war in Kosovo is an essential part of our past and present, given that around 1 million people left their homes.”

According to Shabiu, the collective memory in Kosovo continues to be closely linked to official narratives. “What is obvious is the lack of recognition of resistances others than those known as militant,” she says. “The resistance, like that of the parallel system of education, healthcare, women, and other non-dominant groups in Kosovo, is still in the margins of memory.”

Academic Linda Gusia has spent her career trying to expand notions of resistance in Kosovo in the ’90s in the collective memory, beyond typical views of male soldiers. Photo: Majlinda Hoxha / K2.0.

Linda Gusia, a sociology lecturer at the University of Prishtina, shares a similar opinion. “Our collective memory is dominated by soldiers, and even more, by male soldiers,” she says. “Other contributions are not remembered and evaluated. Heroes are important, but the victims and people who have contributed in many ways, and the experiences and narratives of everyone from every ethnicity, are also important.”

Throughout her academic career, Gusia has been researching roles played by other groups throughout the ’90s in Kosovo, especially protests led by women, and an exhibition based on her work was held earlier this year at the Museum of Kosovo. It focused on March 1998, a month in which four protests organized by women took place, and attempted to keep this aspect of Kosovo’s ’90s history alive through photography and recordings of interviews with those involved.

Personal stories

Personal experiences and narratives are the cornerstone of another organization working toward dealing with the past in a more holistic way in Kosovo, Oral History Kosovo. This online platform gathers stories of people of different ages, entities and vocations, who share their experiences during certain events or periods, including the pardoning of blood feuds in the beginning of the 1990s, experiences from the war, and the declaration of Kosovo’s independence in 2008.