“I have exactly seven bullets, I’ll kill your wife first.” “You should all be slaughtered.” “I’ll slaughter you like a pig.” “I’ll cut your hand off, you have my word.”

These are only some of the threats that have been directed at politicians, journalists and human rights activists in Croatia this month. Their crime? Rejecting to join the government and a large part of the media in denying and dismissing the Hague tribunal’s latest judgements.

On Wednesday Nov. 29, the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia confirmed a total of 111 years of imprisonment for six former political leaders and military commanders of the self-proclaimed ‘Croatian territorial unit in Bosnia and Herzegovina,’ active during the period from October 1992 to April 1994.

The court upheld its key conclusion from the first instance verdict given on May 29, 2013: That war crimes were committed as part of a joint criminal enterprise. Alongside the convicted, the following people were also judged to have taken part: former Croatian President Franjo Tudjman, wartime Defense Minister Gojko Susak, and wartime Commander of the Croatian Army Janko Bobetko.

Jadranko Prlic, Bruno Stojic, Milivoj Petkovic, Slobodan Praljak, Valentin Coric and Berislav Pusic, all had their appeals rejected. Photo courtesy of the ICTY.

For the president of the Herzeg-Bosnia government, Jadranko Prlic, the first instance verdict of 25 years of imprisonment was confirmed. The defense minister of Herzeg-Bosnia, Bruno Stojic, and the commanders of the Croatian Defense Council (HVO), Milivoj Petkovic and Slobodan Praljak, who was an assistant to the defense minister of Croatia, were all sentenced to 20 years of imprisonment. The HVO’s chief of Military Police, Valentin Coric, was sentenced to 16 years, while the head of the office for the exchange of captives, Berislav Pusic, was sentenced to 10 years imprisonment.

Panic, dissatisfaction, and denial

The judgement’s pronouncement was handed an additional dramatic touch by the suicide of Slobodan Praljak. As soon as presiding judge Carmel Agius read the verdict, Praljak screamed: “Judges! Slobodan Praljak is not a war criminal! With disdain I reject your verdict!” At this point, he drank liquid from a small bottle. Not long after that, he died in a Hague hospital. Later it was confirmed that his heart stopped beating due to being poisoned by potassium cyanide.

The verdict immediately caused a wave of displeasure and denial throughout Croatia, and panic attacks for the Croatian government. Meanwhile, the suicide of Slobodan Praljak caused a tide of collective emotions — ranging from mass lighting of candles on the streets to a wave of threats on social networks directed at alleged culprits for the prisoner’s death.

Croatian President Kolinda Grabar-Kitarovic and Minister of Foreign Affairs Marija Pejcinovic-Buric immediately halted their official travels and returned to Croatia.

President of the Croatian Parliament Gordan Jandrokovic rejected the verdict as “unjust.” The same adjective was used by Prime Minister Andrej Plenkovic, announcing that the government would “consider political and legal mechanisms in order to contest allegations from the verdict.”

One day after the verdict, the parliament commenced its session with a minute’s silence for Praljak, boycotted by a part of the opposition. President Grabar-Kitarovic addressed the public with a statement that started by offering condolences to the family of General Praljak, whose death, according to the president, “deeply affected the Croatian people.”

Two days after the verdict, the president and prime minister hosted the political leaders of Croats from Bosnia and Herzegovina in Zagreb. Plenkovic later went to Mostar on Tuesday Dec. 5, in order to, according to an announcement, “calm down” Croats in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The Croatian government showed almost unanimous agreement in objecting to the Hague tribunal’s verdict. Their response was almost the exact opposite of the huge enthusiasm shown five years ago, when the same tribunal acquitted generals Ante Gotovina and Mladen Markac of criminal charges, overturning the guilty verdict and lengthy sentence from the original trial.

Media and political unanimity

No member of the Croatian government has spoken explicitly about the victims of the crimes, for which six people were convicted with 111 years of imprisonment. This is despite the fact that nobody, not even the convicts themselves, have denied that serious war crimes are determined to have been committed “beyond reasonable doubt” by the Hague tribunal.

Alongside Croatian politicians, including the largest opposition parties, the biggest opposition to the verdict came from the Croatian media. On the day of the verdict, the public broadcasting service’s news report used the word “shock” nine times. The same station also invited Ivo Lucic to comment on the verdict. Lucic works as a historian today, but during the Croatian-Bosniak war, he was a senior officer in the HVO’s security service, where he was directly informed about the events and crimes mentioned in the verdict.

It wasn’t only the public broadcaster that chose potentially questionable pundits. Nova TV invited Zlatan Mija Jelic to comment on the verdict — he was the wartime commander of the HVO’s Military Police in Mostar.

The Prosecutor’s Office of Bosnia and Herzegovina has filed an indictment for war crimes against Jelic, but he has avoided coming to court by travelling to Croatia, which refuses to either extradite him to Bosnia and Herzegovina, or to take over the criminal prosecution.

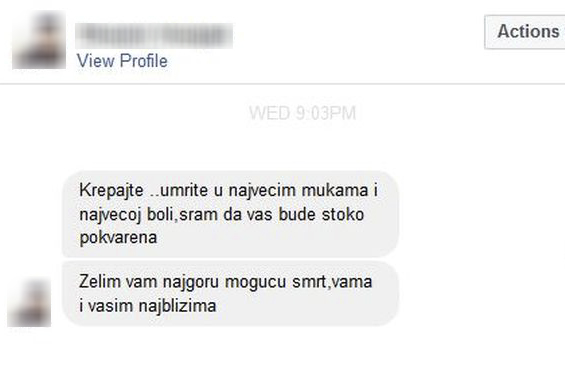

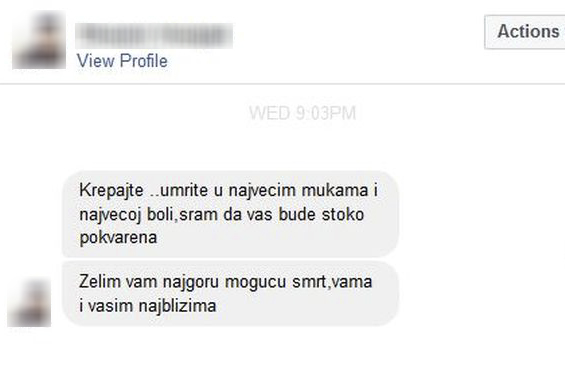

The media and political unanimity, which only a handful of non-influential media, journalists, and opposition politicians opposed, created a threatening climate for all those who disagree with rejecting the Hague verdict. Journalists from the Index portal, Youth Initiative for Human Rights activists, and politicians such as Stjepan Mesic, Vesna Pusic, and Goran Beus Richemberg suffered grave death threats and insults.

“I hope you will die in pain, you should be ashamed of yourselves, you animals. I wish you and your closest ones the worst possible deaths one can imagine.” Message received by Index.hr. Photo courtesy of Index.hr

The abuse was not limited to anonymous threats on social networks. Vladimir Seks, a veteran member of governing party the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ), and also a member of the party’s Advisory Council, made accusations against the former president of the republic, Stjepan Mesic.

He said that Slobodan Praljak’s blood was on Mesic’s hands, and invited the State Prosecution to reconsider Mesic’s testimony at the Hague tribunal during the trial against HVO general Tihomir Blaskic. After receiving threats, Mesic was assigned police protection.

Call for politicians’ accountability

Despite the denial, there are also other voices in Croatia. The Citizens’ Board for Human Rights (GOLJP) sent an open letter to the government and parliament, inviting them “to show the strength of responsible politicians,” and “to face a part of the negative heritage of Croatian politics in Bosnia and Herzegovina.”

“Instead of declarative and hypocritical ‘condemnation of all crimes,’ we suggest that the Government of the Republic of Croatia finds means for the compensation of victims of concentration camps ran by the HVO,” said the open letter from GOLJP, signed by 30 public figures.

The president of the NGO, Zoran Pusic, told K2.0 that “the verdict is not a judgement on the Croatian people in Bosnia and Herzegovina or in Croatia, but it is a judgement on part of Tudjman’s politics towards Bosnia and Herzegovina from late 1992 to early 1994.”

Pusic said that it “depends on Croatian politicians” which consequences this verdict will have for the political landscape in Croatia. “If the Croatian government finds the political strength and state wisdom to distance itself from those politics, which many Croats have done in the past 25 years, this will contribute to improving the situation in Croatia, its reputation in the world, stability in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the relations between Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina,” Pusic stated. “Otherwise, a trend we have been facing in the past few years will continue to grow.”

Philosopher and political analyst Zarko Puhovski believes that “the only rational controversy” surrounding the verdict is that it is “textually just, and contextually unjust, if it is compared to the verdict of Ratko Mladic, where no joint criminal enterprise with Serbia is mentioned.”

However, Puhovski also rejects the frequent allegations made in recent days in Croatia, that Croatia had been convicted, unlike Serbia, for a criminal enterprise in Bosnia and Herzegovina. “This isn’t correct. Serbia was convicted in one of the very first Hague tribunal verdicts, that of Dusko Tadic, and everybody keeps forgetting that Slobodan Milosevic was indicted and tried, even though he died before a verdict could be reached,” he explained to K2.0.

Despite all of this, Puhovski does not expect a sobering up to happen in the country. “Croatia makes war crimes part of its society. Due to this kind of behavior, these crimes are now my crimes also. Both the government and opposition don’t have the strength to distance themselves from Tudjman and Susak. They don’t have the strength to do what even Aleksandar Vucic has done when he’s needed to for political reasons,” he said.

Puhovski, unlike some Croatian lawyers, does not believe that any kind of revision of the verdict is possible, and doubts that potential lawsuits of victims against Croatia have any chances of succeeding.

Many questions remain. What happened to the victims? They are rarely mentioned in Croatia, except by weak and infrequent opposition voices, NGOs and some media. Should Croatia be compensating these people? Should it provide them with moral and material satisfaction? Perhaps with the same model Montenegro used to symbolically apologize to Croatia and give constant material reparations, willingly compensating for the destruction in Konavle, close to Dubrovnik, in 1991.

“I am convinced that it should,” Zarko Puhovski responded. “But I am also convinced that it won’t happen.”K

Feature image courtesy of the ICTY.