ECHOES THAT REMAIN

Artikulli përmban

Over the last 20 years, tales of war have often formed part of the conversations of hundreds of thousands of Kosovars: from anecdotal, comical situations to terrible, tragic tales of torture, abuse and death.

Each oral history, together with visual and written documentation, contributes to a comprehensive portrayal of the war: dates, locations and people affected by infamous offensives, expulsions and casualties. However, in most cases, the tales conclude with the end of the war.

Rarely have these discussions included life after 1999; the difficulties of living in a war zone, the tribulations of moving from one place to another and the different traumatic experiences that continue to leave a mark and emerge through a wide range of intensive reactions and emotions.

Simply seeing day-to-day objects like flour, tractors, shoes, watches or traffic can cause many people to relive painful memories. Many others continue to experience shocking anxiety and nightmares.

In this piece, we present four tales that explore four different experiences of the war. Each tale confronts the recurring and intrusive memories of a traumatic past.

FIDAN’S TALE

In Spring 1999, KLA staff stationed themselves close to Fidan Hoxha’s family home in Peqan, Suharekë. They ordered the family to leave. The family’s close proximity to the troops was a risk, as they could easily become a target of the Serbian forces. The Hoxha family immediately left.

In March of that year, Fidan was only 16. But because his older brothers had already joined the KLA, it was left to him to drive a small single-axle tractor to transport food. He followed his father, who was driving his tractor toward Pagarusha in Malisheva with 18 family members in the back. They reckoned that they would be safer there.

After staying two days in Pagarusha, Serbian forces came toward them from Rahovec. Fidan and his family were forced to leave again. This time, the destination was Bellanica village — eight kilometers from Malisheva — where around 100 displaced people from Malisheva and Suhareka were living. They had all been expelled from their homes during the Milošević regime’s ethnic cleansing campaign.

Fidan’s relatives planned to stay longer in Bellanica, since they had relatives in the village who provided shelter to people. However, after only one night, Serbian forces gave the order to evacuate the village, forcing Albanian civilians to walk toward Albania.

A frightened Fidan pushed his two-wheel tractor in the long line of people that were headed to Albania. He stayed behind his father.

However, when Serbian forces began demanding money from all the drivers that were transporting refugees, Fidan left the two-wheeler behind and hopped on the tractor with his family. His father was forced to give money to Serbian soldiers, for himself and his son, whenever they demanded it. “They would ask for money every 10-20 meters,” Fidan says.

Driving for survival

The line moved slowly. A tractor that was full of women and children had been left behind by one of Fidan’s relatives, because all the men had gone to hide in the woods. So Fidan decided to transport 40 people with that tractor, even though he had very little experience driving it.

After driving about 50 meters, a Serbian policeman forced him off the tractor and into the basement of a nearby school. They touched his face to see if he had grown a beard before and then inspected his clothes.

“I was wearing thick clothes, so they told me: ‘You have a uniform. Take off all your clothes!’” Fidan recalls. “I reached down to my ankles to pull up my pants so that they could see that I didn’t have a uniform underneath. I actually had two pairs of pants on but he said, ‘Take off all your clothes,’ so I did.”

After a few minutes, the Serbian policeman was summoned by one of his colleagues and left the basement, leaving Fidan naked. When he realized that no one was coming back for him, he put on his clothes and went back to the tractor, joining the line that was heading toward Malisheva.

Fidan explains how Serbian forces put the Albanian national flag on the ground at the main crossroads in Malisheva, so that vehicles would drive over it. Believing that the Serbian soldiers weren’t looking at him, he maneuvered the tractor so he didn’t drive over the flag. But he was spotted by one of the soldiers.

“I didn’t notice the Serbian soldier on my right. He shouted at me in Serbian: ‘Stani!’ He was telling me to stop,” he says. “He slapped me twice and made me go back. I drove over the flag with three pairs of wheels.”

Fidan had very little experience driving tractors but with the responsibility of transporting 40 refugees, he continued to drive the tractor towards Rahovec. When they came to a place called Rrasat e Rahovecit, one of the tractors that was transporting 30 people got a flat tire.

“We connected the rear of the tractor to the back of the tractor that I was driving, creating a tractor chain,” he says.

Fidan says the situation was very dangerous, because now he was transporting around 70 people, feeling a lot of responsibility and fear.

The road to Albania went on for three days. He was exhausted from the difficulties that he faced. Fidan says that he fell asleep driving multiple times. At one point he even hit the tractor in front of him.

“Many tractors saved many people.”

Unfortunately, rain complicated much of the trip. The tractor was uncovered and the only clothes they had got wet.

“We didn’t have any other clothes. My body dried my clothes,” he says.

Fidan worried about his family a lot. He didn’t reunite with them until they arrived in Albania. The line stopped so many times, the tractor he was driving was left behind.

After driving for three days and two nights, they crossed the border into Albania.

Fidan becomes very emotional and doesn’t say much when he describes his feelings crossing the border.

“Oh, when I met my dad in Kukës… I don’t even know!” he says, as he wipes away his tears and stops talking.

‘God and Fidan’

Fidan later drove the tractor from Kukës to Peshkopi, where he and his family found shelter as refugees. After three months, they received news of Kosovo’s liberation via a phone call with Fidan’s uncle, who called from Switzerland.

Fidan, his father and the owner of the house where they had sheltered, immediately set off to Kosovo to find out the condition of their house in Peqan.

They found the house burned down and the farm full of dead cows. After they cleaned the farm, they returned to Peshkopi to fetch their other relatives. Fidan, his father and his brother went back to Kosovo with the tractor, while the others took a taxi.

Now 37 years old and the father of three children, he has a special connection with tractors. Although he doesn’t own one today, he says he often takes his Dad’s tractor for a drive.

“When I drive a tractor or see one in the street, it is impossible not to think of that time, that struggle,” Fidan says. “When I’m driving a tractor, I recall the whole story, as if I am watching it on TV. Many tractors saved many people.”

The families that Fidan took to Kukës are forever grateful to him.

“The women often say: ‘God and Fidan,’” he says.

***

BLERIM’S TALE

Blerim Deliu was a primary school pupil in the village of Abri e Epërme in Drenas when he heard his parents and fellow villagers say “The war has started!”

The alarm was first raised in March 1998, when Serbian forces began their infamous offensive against the Jashari family in Prekaz, 20 kilometers from Abri village.

In late summer 1998, Serbian forces were stationed in Likovc village, which was next to Abri. Seeing that the shelling had started and that the danger was only 7 kilometers away, Blerim’s family, like many others, retreated to the woods near Vuçak village.

Blerim, then 16, didn’t stay with his family in the woods the whole time. Along with some of his peers he was constantly exposed to danger as they went to the village to get food for their relatives and do some of the housework. The men of the village, including Blerim’s father and brother, had already joined the KLA.

The last week of September, the shelling that came from Likoc village became more intense, and Abri was being destroyed. Blerim remembers how he saw his house burning along with many others.

“We ran to put out the fire, but they burned everything,” Blerim says.

A little later, with the houses still on fire, Blerim and two of his cousins, Adem and Zeqir, decided to go to the village again to extinguish the fires and get food.

Lined up one after the other, as they walked along a fence, Blerim, Zeqir and Adem approached their houses. Suddenly, at a crossroads 3 meters away, they were faced with a Serbian paramilitary soldier who was exiting a garden.

Surprised to see them, the paramilitary ordered them to stop, but the boys didn’t.

Blerim recalls the last words he heard from Zeqir.

“Adem, this is it.”

A few seconds later, the bullets hit Adem.

Unable to go to his family, Blerim went to the village’s Hisenëve neighborhood, where 40 people were camped out next to the river.

Blerim’s father was a renowned teacher; one of the women recognized Blerim as his son and gave him food, shoes and a jacket. Blerim says that he will never forget this act of kindness.

Blerim slept by the river that night. The next morning, when they woke up, they were surrounded by dozens of Serbian soldiers.

A commander ordered the men, women and children to be divided into separate queues. Blerim didn’t move, staying among the women. One of the Serbian soldiers noticed.

“Suddenly, a paramilitary approached me, grabbed me by the throat and lifted me up,” says Blerim, adding that he asked the others to translate the Serbian ordering him to get up.

“I lost hope. I thought that was it, that was the end for me. I thought they had noticed that I was the one who had escaped before and that they would murder me.”

However, the Serbian soldier let him go and Blerim sat down again. Driton, a teenager who Blerim had talked with the night before, didn’t have the same fate. Together with a few other men, they were taken to Likoc by truck to be executed.

“I heard later that they decapitated him [Driton] as soon as they got to Likoc,” Blerim says.

A commander who spoke Albanian ordered the remaining people to stay where they were until 5 p.m..

Shortly after 5 p.m. on November 25, 1998, Blerim set off for his village. He says he will never forget what he saw when he arrived. A few hours earlier, the Deilaj family had been murdered. They were Blerim’s cousins.

“I saw elderly people who couldn’t leave their homes because they were paralyzed or very old. They killed them, decapitated them, they just took them out of their homes, threw them in the garden and burned their houses,” Blerim says.

Out of the 23 murdered members of the Deilaj family, the Serbian paramilitaries spared only four children, all under the age of four. Blerim witnessed the shocking condition of those children in that moment. They initially refused any kind of help that people tried to give them.

“We barely stabilized them. They didn’t want to take off their jumpers and change their clothes. They were in a really bad state,” recalls Blerim, who was himself in a very bad mental state at the time.

The next day, Abri was visited by the OSCE and many foreign journalists. Blerim refused to speak to them because of his severe emotional condition — it took him a year to begin to recover.

After the end of the offensive, in the first week of October 1998, Blerim and his family returned home.

After living in the remains of the destroyed houses, in Spring 1999, Blerim’s family, together with other families from the village, were forced to leave their homes again. Blerim’s family returned to the woods near the village of Vuçak, while Blerim and his father went to the Berisha mountains, where thousands of Albanian civilians stayed until the end of the war.

Living a nightmare

The postwar period wasn’t easy for Blerim. Every day he lived with the trauma of his wartime experiences. Even today, he cannot get over the nightmare of the events that unfolded two decades ago.

Today he is 37 years old, married and a father to two daughters. He often thinks about how he made it out alive.

“As soon as I drift off to sleep, I feel like they are trying to kill me.”

“I see the cemetery, I see Adem, I see Zeqir, I see everyone; I think about how odd life is, because I could have been there too,” Blerim says. “They killed me 100 times, because they fired the Kalashnikov at me until they ran out of bullets.”

In Prishtina’s psychiatric hospital, he has been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. He is convinced that there is no cure.

“At the hospital they told me that it is a bit problematic, because it is an old war trauma that will only develop further,” explains Blerim, adding that he also spoke to imams but to no avail.

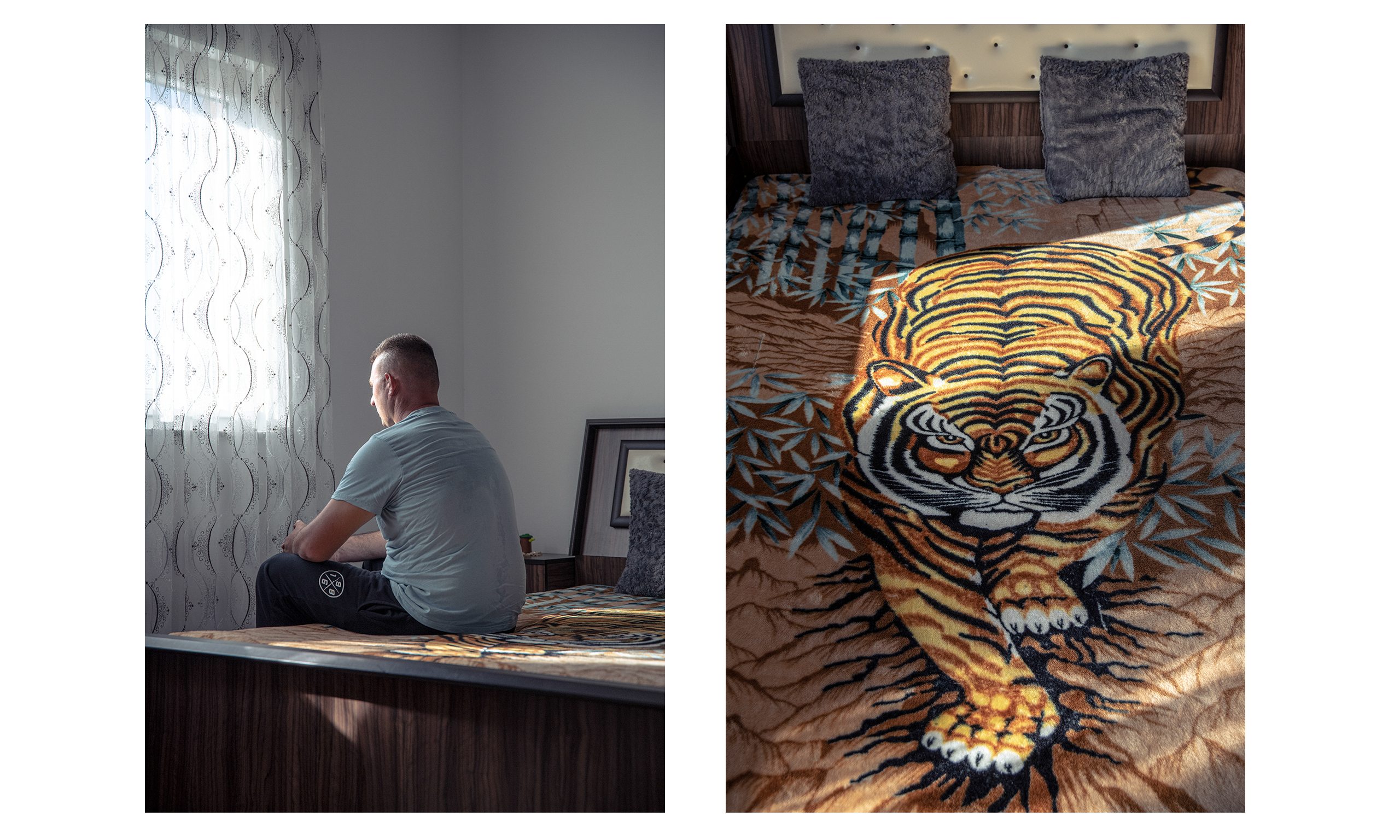

In his two story house in the suburbs of Fushë Kosovë — where he works as a truck driver for a concrete factory — he lives with his wife, children and brother. His relatives never let him sleep alone in the house because he is troubled by his dreams.

“As soon as I drift off to sleep, I feel like they are trying to kill me,” explains an emotional Blerim. “At that moment, I have to wake up and run — to save myself! Just like I did in the war.”

He hopes that his children will never see him waking up from these dreams, because he says that he can’t control himself.

He even suffered injuries at one point.

A few years ago, when he was living in a rented apartment in Fushë Kosovë, he jumped from the second floor balcony after having a nightmare.

“I injured both my knees very badly,” he says.

Since then, Blerim only sleeps on the first floor.

***

For Fatlum Sadiku, the war ended a year later, in June 2000, when he left his apartment in north Mitrovica.

FATLUM’S TALE

Forty kilometers away from Blerim, in north Mitrovica, Fatlum Sadiku, an only child, lived with his family. Their apartment was only 50 meters away from Yugoslav state institutions: the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the police station, the court and the prison.

In the semi-urban environment, as Fatlum describes it, they lived alongside and socialized with people of different ethnicities.

In Spring 1998, the war intensified with massacres and battles in central Kosovo. Fatlum and his family feared the worst. Residing so close to the authoritarian center of Mitrovica made the situation all the more frightening. Serbian forces would set off from Fatlum’s neighborhood to attack different parts of Drenica.

With the situation becoming more severe, all schools were closed in Mitrovica. Fatlum was an excellent student at the time. He had just received his grades after finishing the first semester of grade five. For the first time, he had got a four out of five in math and was feeling quite down.

“This was a preoccupation of a city kid, that was perhaps shameful for me. But it was not done on purpose,” he says.

When the game ends

March 13, 1999 was supposed to be a market day at the edge of the Ibër river but Serbian forces shelled the market in south Mitrovica, killing six Albanians and wounding 128 others. Before the NATO bombing campaign started, Albanians who lived in the same building as Fatlum had begun to show wartime solidarity, making arrangements to ensure that everyone was sheltered.

Fatlum’s family of three lived on the fifth floor of the building. When the news broke that NATO would attack Serbian targets, it became too dangerous for them to stay at their apartment. Their balcony faced the police station that was later bombed by NATO air forces.

On March 24, in one of the last evenings at their apartment, Fatlum’s mother, who also spoke Turkish, was watching the news on NTV, a TV channel based in Turkey, which is a NATO member state. She heard the phrase ‘NATO vurdu,’ which means ‘NATO strikes.’

The next day, their Albanian neighbor knocked on the door, asking them to hide in his apartment, since he was living on the first floor and it was safer there — and so they welcomed him in.

At 2 a.m. on April 20, 1999, four or five masked Serbian paramilitaries knocked on their neighbor’s door and began questioning his decision to shelter an Albanian family. The scene ended with him being brutally, and fatally, beaten.

“He was so badly beaten that we couldn’t even find his eyes, nose, ears or mouth,” Fatlum says.

Just before 5 a.m. that morning, they were ordered by Serbian forces to leave the building and cross the Ibër bridge to the southern side of the city.

Fatlum’s family was heading to the town of Vushtrri. His blind father insisted on going there, saying, “If we die in Vushtrri, at least Albanians will bury us.” He was convinced that would not be the case in Mitrovica.

In Vushtrri, along with other displaced people, they were sheltered by Fatlum’s mother’s relatives. They were expelled from Vushtrri on May 4, two days after the Studime massacre, which they learned about from Euronews, even though they were only 2 or 3 kilometers away from the scene of the crime. Euronews also reported on the police station’s bombing by NATO.

“This speaks a lot about how newsworthy the conflict in Kosovo was. You would hear about your city or your apartment on Euronews,” he says.

On the day of their expulsion, policeman Zoran Vukotić, who was later sentenced to six years imprisonment in Mitrovica for the abuse and torture of Albanian civilian prisoners in 1999, entered the garden of the house where Fatlum’s family was sheltered. All the people staying there were in one room, except Fatlum’s father, who had gone out on the balcony to smoke a cigarette.

“I’d say, ‘Look, no one kills a dog.’ Perhaps they even killed dogs, but no one kills birds. ‘If only I were a bird.’”

When Fatlum went out to the balcony to get his dad, he saw the perplexed Serbian policeman looking at his father. Fatlum’s father is blind, so he couldn’t see the policeman and he looked like he just didn’t care. To this day, Fatlum is amazed the policeman didn’t execute his father.

Breaking the window with the butt of his gun, Vukotić ordered the people to evacuate the house immediately. When he recognized some families that he had evicted previously, he became furious: “Is this Albania?!” he said, swearing at and insulting them.

Surprisingly calm, Fatlum’s mother reached for her boots that were next to Vukotić’s legs, making the policeman very angry. Fatlum explains that his mother was an employee of the Yugoslav system and as such she could never imagine that there would be a war. She subconsciously believed in Yugoslavia’s longevity.

“When he saw her getting so close, he started to swear and fire his gun in the air. ‘I’m going to shoot three more times. If you don’t leave, I’m going to kill you,’ he said. I started to cry and gestured to my mother to leave.”

They left and walked for about 20 meters before they saw smoke coming from the house.

After this, Fatlum and his family found shelter at a relative’s house in Vushtrri. On May 22, Serbian forces committed one of the largest massacres of the Kosovo war, while Fatlum and dozens of others were staying silent in a house only 100 meters away.

Fatlum says that during that time he started to become envious of animals.

“I’d say, ‘Look, no one kills a dog.’ Perhaps they even killed dogs, but no one kills birds. ‘If only I were a bird,’” he says. “Like that Troja song: ‘When the sky opens, you’ll see the angels,’ but I couldn’t see any angels, I was envious of birds.”

‘Time to see the angels’

Fatlum says that the days when NATO forces entered Kosovo and Serbian forces retreated felt like centuries full of nightmares.

“The garden of the house had a tree in the middle. My father and I were talking to each other under its shade: “I wonder if they’ve reached Klinë or Ferizaj,” Fatlum says. “And that’s when I heard the first cries: ‘NATO! NATO!’”

Fatlum looked through a hole in the garden fence and saw a few Albanian teenagers burning the flag of the former Yugoslavia. Like many others, he ran toward a British tank.

“It was time to see the angels,” he says.

The Sadiku family returned to their apartment in north Mitrovica.

In the days after the war’s end, it quickly became clear that although the armed conflict had stopped, there was absolutely no security for minority groups who lived south of the Ibër bridge — hundreds of civilian Serbs, Roma and others who didn’t leave the country were killed or became victims of abuse.

There was also no peace for Albanians in north Mitrovica, as they lived in constant danger of continuous attacks coming from the Serbian parallel structures’ criminal gangs. That culminated in February 2000, when a group of Serbian volunteers known as the Bridge Watchers killed 10 Albanians, while 12,000 others were expelled.

Due to the tense environment, in June 2000, Fatlum’s parents decided to return to Vushtrri and start a new life. Throughout his life, Fatlum has chosen not to make a big deal of his war experiences, finding comfort in the fact that his loved ones survived. That was not the case for thousands of Albanians.

After finishing school in Vushtrri and university in Prishtina, Fatlum went on to finish a master’s program in Istanbul. He lived there for four years, until 2016. The Turkish capital helped him reflect on his life during and after the war.

Fatlum was brought back to his own experiences of war as he followed the development of court cases against war criminals like the late Oliver Ivanović, who was accused of killing Albanians, and the policeman Zoran Vukotić, who was found guilty of torture against Albanians who were detained in Smrekonica prison.

Fatlum was disappointed with the justice system because Ivanović’s case went to retrial, while accusations against Vukotić for his complicity in the Studime massacre as well as the campaign of systematic rape were not tried in court.

“That added fuel to the fire that is my experience of war, because those two figures were present in my experience,” Fatlum says. “Vukotić almost killed my mother, and while I never saw Ivanović, he was the head of the Bridge Watchers.”

Indignant at the situation after the war, Fatlum says that he is very disappointed with Kosovo’s political leaders who, he says, have violated Kosovars’ experiences of the war.

Editor: Dafina Halili

Multimedia Content Editor: Cristina Marí

Design: Kokrra / Skins Agency

Development: Harisia

This publication is supported by the ‘Civil Society programme for Albania and Kosovo’, financed by the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and managed by Kosovar Civil Society Foundation (KCSF) in partnership with Partners Albania for Change and Development (PA). The content and recommendations do not represent the official position of the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Kosovar Civil Society Foundation (KCSF).