The elections are over, it's time to move on

VV now has the opportunity to translate its electoral mandate into institutional stability.

In-depth

More

The elections are over, it's time to move on

VV now has the opportunity to translate its electoral mandate into institutional stability.

Perspectives

More

Coded gender discrimination

Artificial Intelligence reproduces inequalities against women.

Longform

More

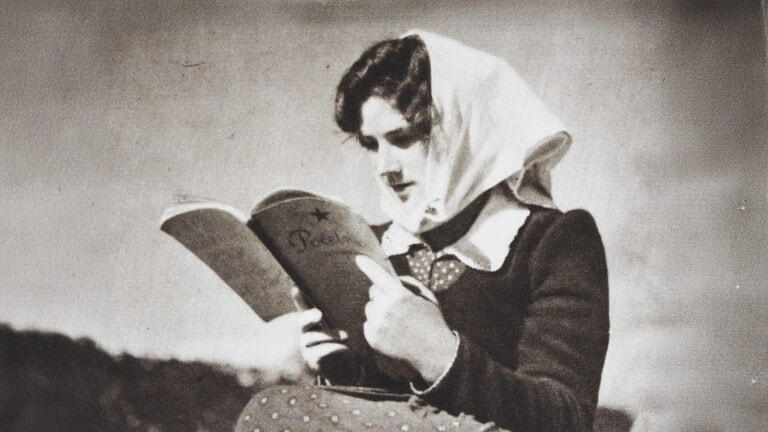

Women’s Anti-Fascist Front in Kosovo

Between emancipation and propaganda, and under conditions of survival

Videos

More

Recommended

Women’s Anti-Fascist Front in Kosovo

Between emancipation and propaganda, and under conditions of survival

Photostories

Explore more

Become a member, support our journalism.

At Kosovo 2.0, we strive to be a pillar of independent, high-quality journalism, in an era where it is increasingly challenging to uphold these standards and pursue truth and accountability without fear.

To ensure our continued independence, we are introducing HIVE, our new membership model, which offers those who value our journalism the opportunity to contribute and become part of our mission.