A betrayal of literature

How and why the Nobel Committee for Literature awarded Peter Handke.

The passing of time has ruled that Hamsun’s work is an unavoidable part of world literature history, and that with his novel “Hunger,” he revolutionized the modern novel.

The writer needs to be on the side of the human, because otherwise his work becomes a cenotaph.

If he truly had good intentions toward the Serbian people and its culture, he would stand on the side of the writers who resisted evil.

The motivations behind the Nobel Prize Committee’s decision aren’t all that blurry. Last year’s sexual scandal had to be mitigated by some larger scandal.

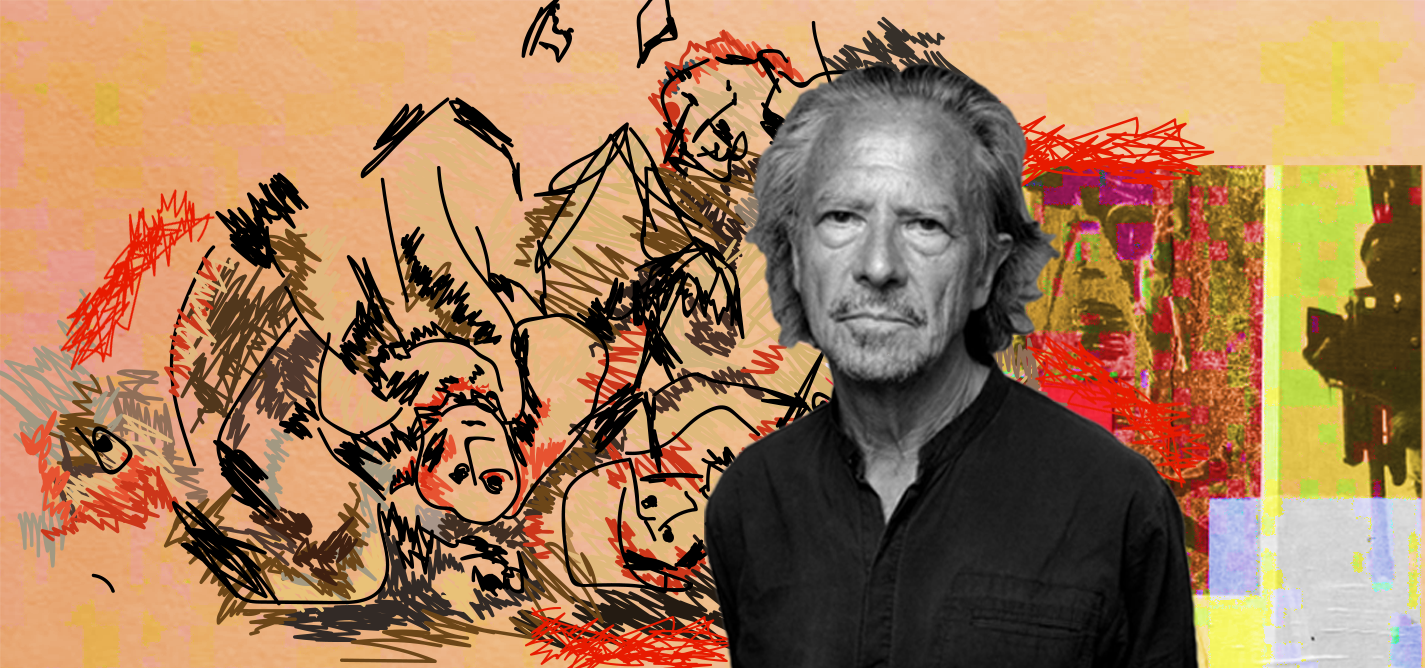

Đorđe Krajišnik

Đorđe Krajišnik is a literary critic and a journalist at the Oslobođenje daily newspaper and the Dani magazine. In October 2017, he worked as a resident for the Berlin daily Der Tagesspiegel. His literary critiques and other texts have been published in magazines and on websites across the Yugosphere. His publications have been translated into English, German and Albanian. He reviewed and edited several books. Currently, he is working on his first fiction book that will be published soon, should the Muses be in his favor.

DISCLAIMERThe views of the writer do not necessarily reflect the views of Kosovo 2.0.

This story was originally written in Serbian.