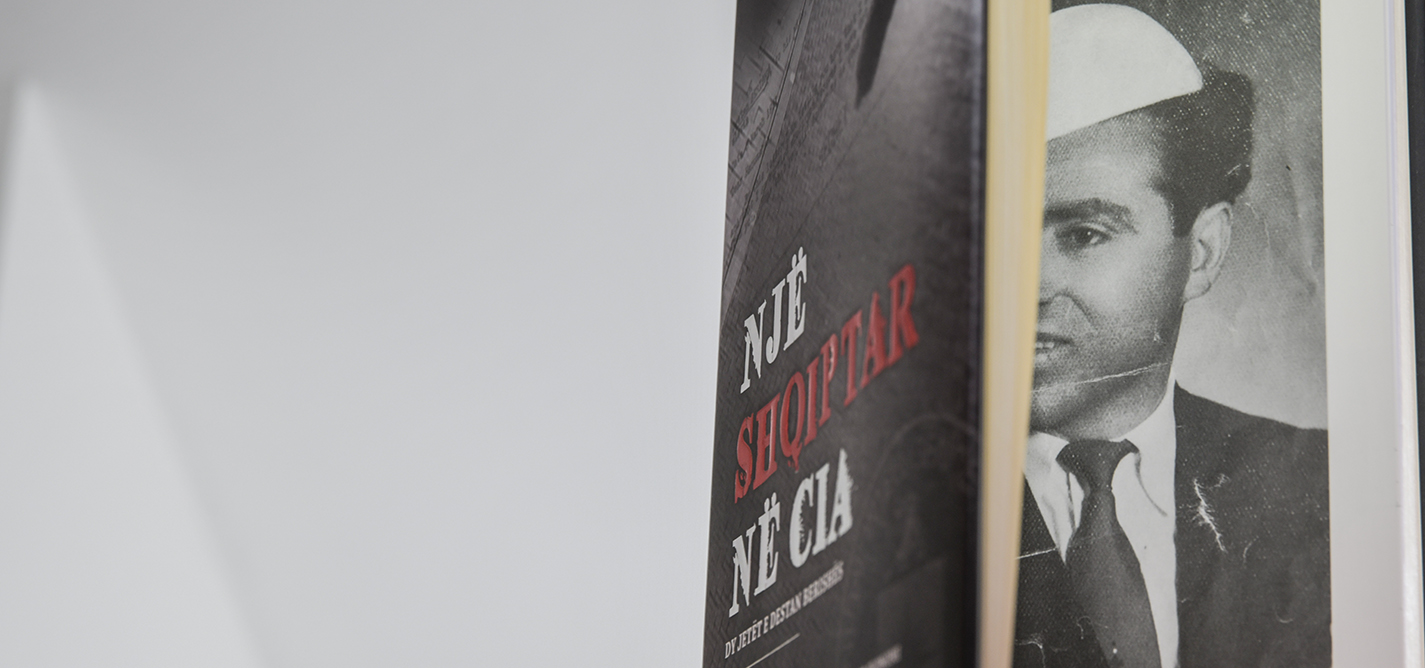

An Albanian in the CIA and the CIA in Albania

A book we didn’t know was needed.

The biggest challenge in the writing of the book was that the Albanian archives contain very little documented material.

His life is a representation of a whole era: that of relations between Albanians and communism against the backdrop of the Cold War.

According to Demi, there is a notable need for these kinds of Albanian language books.

Fitim Salihu

Fitim Salihu is a former K2.0 staff journalist, covering mainly politics and governance. Fitim has a bachelor’s degree in political science from the University of Prishtina.

This story was originally written in Albanian.