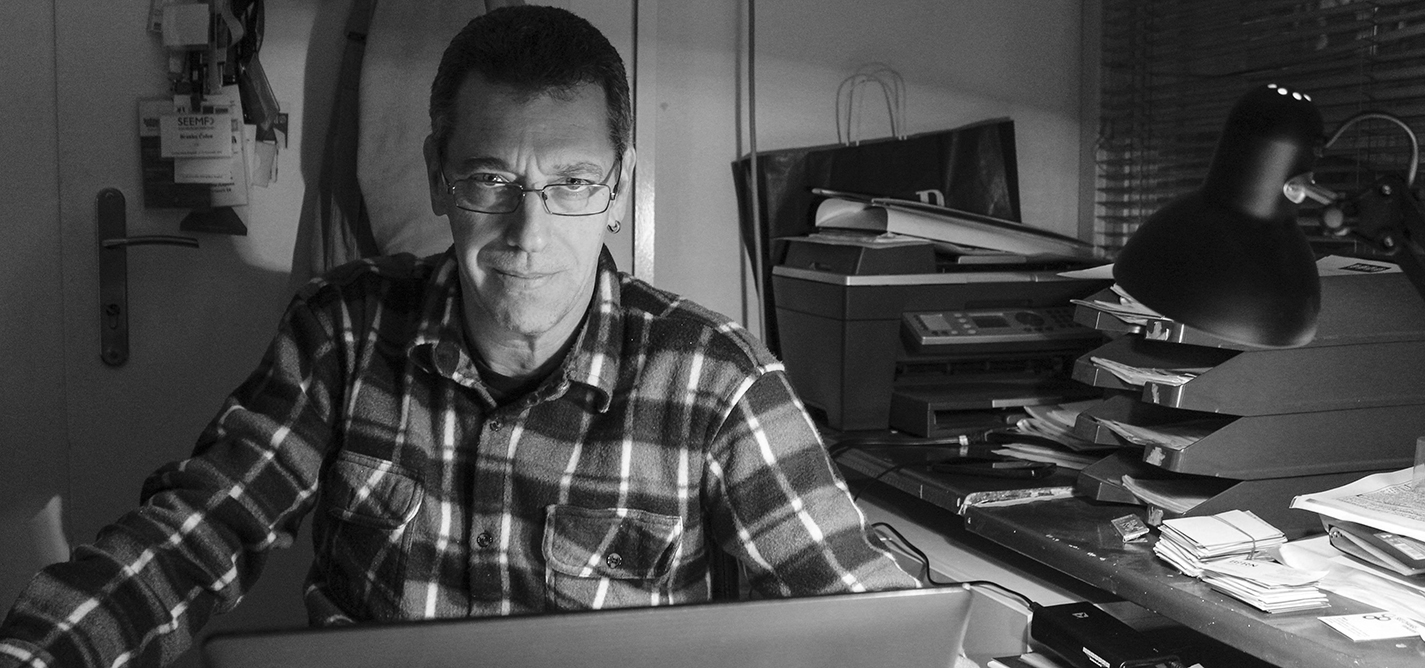

Branko Cecen: Investigative journalists face media lynchings, threats and physical assaults in Vucic's Serbia

Center for Investigative Journalism of Serbia (CINS) director on why he walked out of prime minister’s speech at regional media conference.

"Politicians should understand that a country starts to develop only when the media are not tools in their hands, means of propaganda in their struggle for power."

"Nobody goes out alone, late at night, no little dark streets. If the situation is really compromised, we send our reporters out of the country for some time."

Luka Zanoni

Luka Zanoni is editor in chief of Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso Transeuropa, an Italy-based think tank. He completed post-graduate studies in history and philosophy at the Bocconi University and has a degree in Theoretical Philosophy from the University of Milan. From 1999 to 2005 he was an editor and translator for Notizie Est-Balcani and from 2002 to 2003 he carried out editorial work for the monthly publication Balcani economia.

This story was originally written in English.