Ermela Teli: In socialist paradise it never rains

Director Ermela Teli reflects on art, censorship, and the absence of rain in socialist realism during communist Albania.

|28.08.2025

|

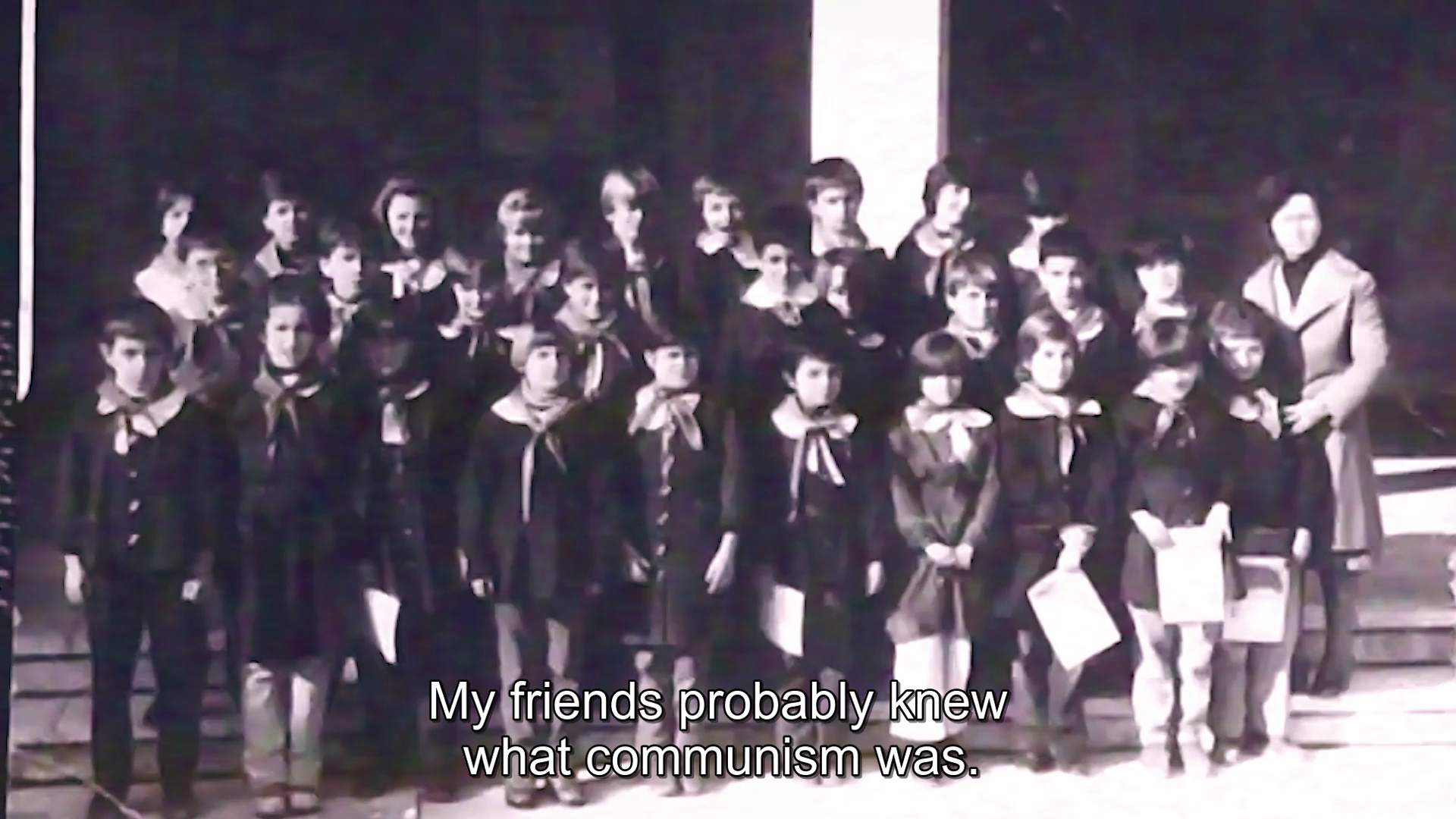

Still from the film “In Socialist Paradise (It Never Rains)”

But back then, that was a problem — you had to see things the same way as everyone else. You couldn’t see them differently; you couldn’t have a personal perception of reality. Rain, grayness, or darkness in painting were defined as pessimism — and pessimism was forbidden. You had to be happy, part of a happy ideological collective that accepted reality as the state directed it, not as you yourself saw it.

Photograph: Scene from the film “In the Socialist Paradise (It Doesn’t Rain)”

Through my research, I came across a study by critic and art historian Gëzim Qëndro, which explored the absence of rain in socialist realist art. This study appears in a chapter of the collection “Socialist Realism as History and Method,” curated by Raino Isto and published by the house Pika pa sajësë. The book is a compilation of essays and studies collected by Isto from various authors.

test

Still from the film “In Socialist Paradise (It Never Rains)”

It wasn’t difficult, because the fall of communism naturally led toward change. That was a dramaturgical point for me; it opened a new chapter. But even there, I incorporated my personal perspective. For me, the fall of communism didn’t mean that we had entered a democratic society. Albania was still at war; people were being killed. I experienced the fall of communism through the lens of conflict, not liberation. In the film, the personal and historical perspectives are intertwined throughout.

Valmira Rashiti

Valmira Rashiti is an editor at K2.0. She has a bachelor’s degree in Law and Cultural Anthropology from the University of Prishtina.

This story was originally written in Albanian.