Lea Ypi: Dignity is not something waiting to be recovered from the past

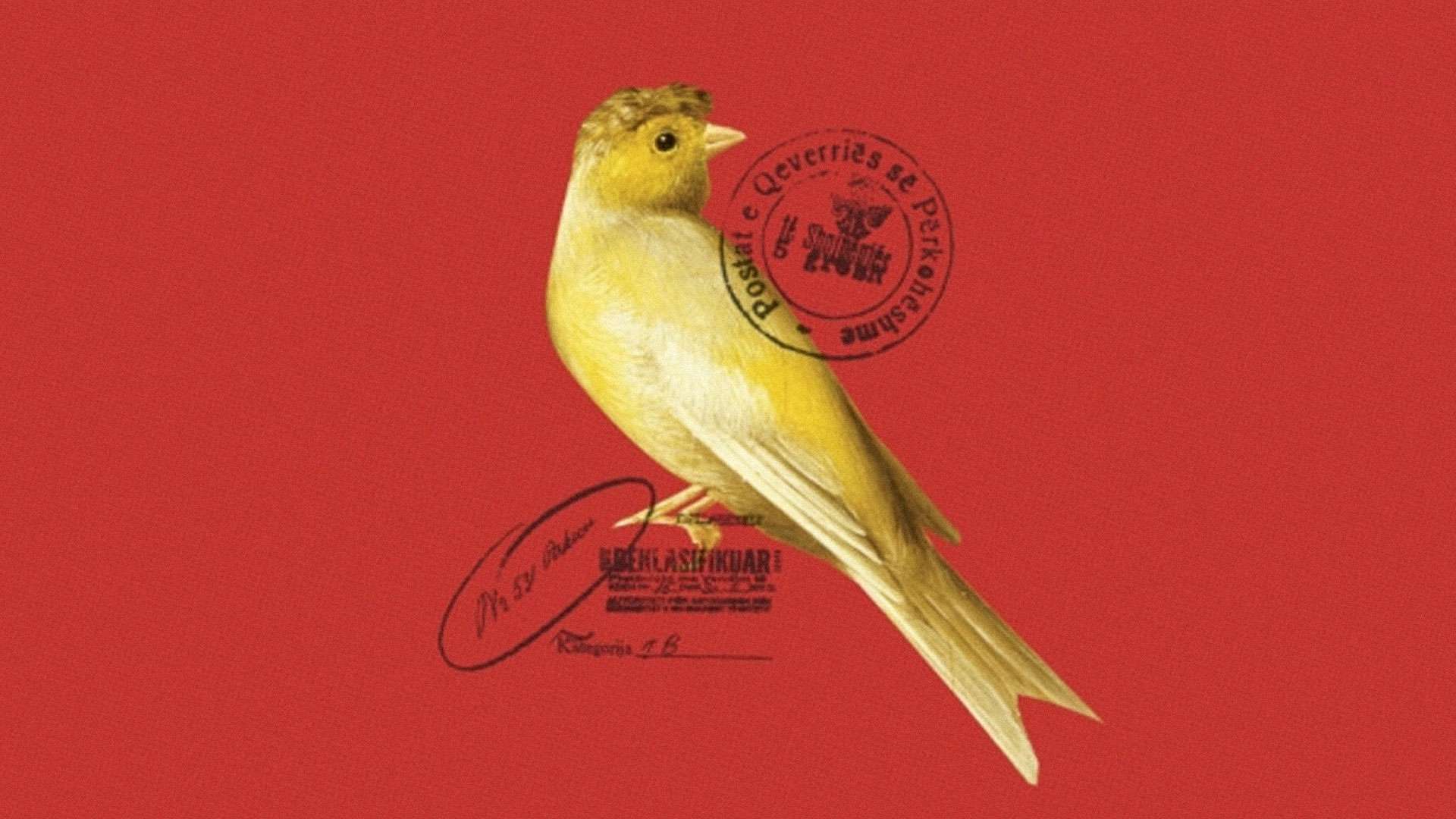

Ypi discusses memory, survival and the search for truth in her recently released novel, “Indignity”.

Gresa Hasa

Gresa Hasa is the co-founder and editor-in-chief of Shota, an Albanian feminist magazine. She is an independent publicist, regularly contributing political commentary in Albanian, regional and often international media. Previously, she was engaged in grassroots political organizing in Albania. She currently resides in Vienna, Austria, where she continues her academic and professional career.

This story was originally written in English.