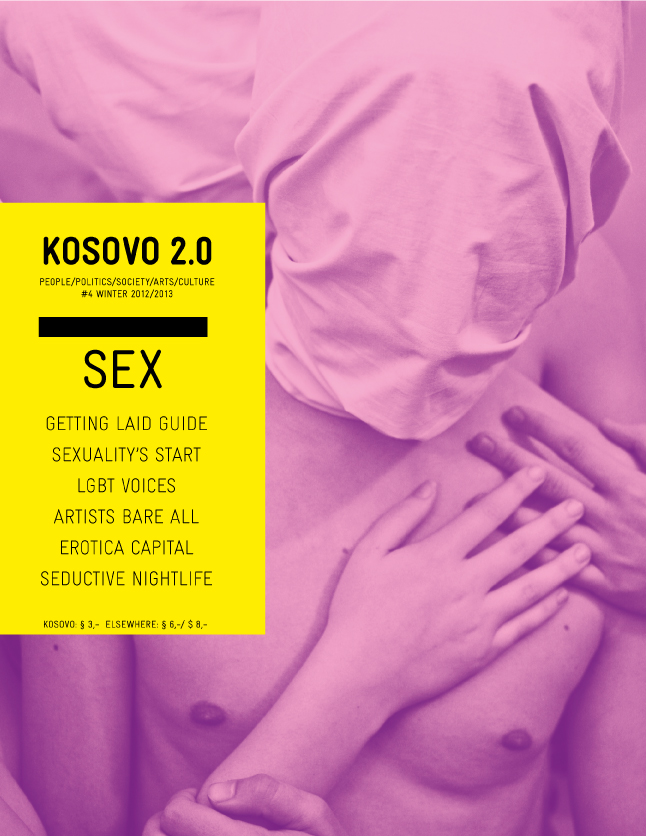

#4 SEX

Unpacking how sex and sexuality are deeply political: this issue of Kosovo 2.0 examines how bodies are controlled and regulated, and how patriarchal norms and heterosexuality limit personal freedom, ideas of gender and identity. “Sex” combines analysis and personal testimonies that cover LGBTQ+ narratives, intersexuality and sex work, while reflecting on the stigma, homophobia, and legal-social constraints that hinder sexual and gender freedoms in Kosovo and the region.

Our message and position are clear. We see this magazine as a call to everyone to come out and break free with their sexuality.

Besa Luci

Besa Luci is K2.0’s editor-in-chief and co-founder. Besa has a master’s degree in journalism/magazine writing from the University of Missouri’s School of Journalism in Columbia, U.S..

This story was originally written in English.