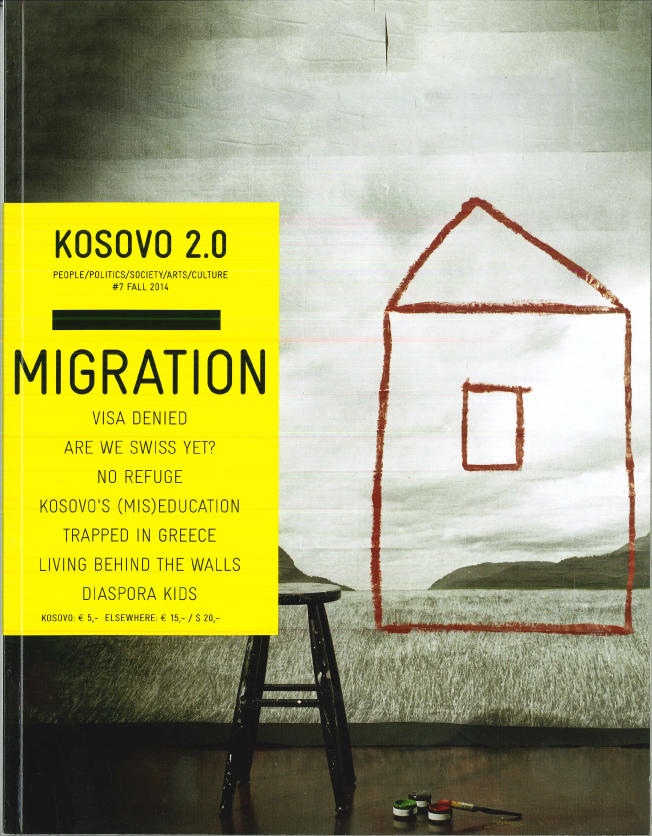

#7 MIGRATION

This issue of Kosovo 2.0 examines how migration — whether by workers abroad, refugees or contemporary economic emigrants — shapes identity, home and belonging. Sensitive to the political and social structures that define who can and cannot move, “Migration” presents personal stories of Kosovars across generations (from guest workers under Yugoslavia, wartime refugees and today’s youth) alongside a broader analysis of migration rights and policies.

Being from Kosovo offers us great insight into how migration plays out, unfolds and gets packed and unpacked over and over again.

Besa Luci

Besa Luci is K2.0’s editor-in-chief and co-founder. Besa has a master’s degree in journalism/magazine writing from the University of Missouri’s School of Journalism in Columbia, U.S..

This story was originally written in English.