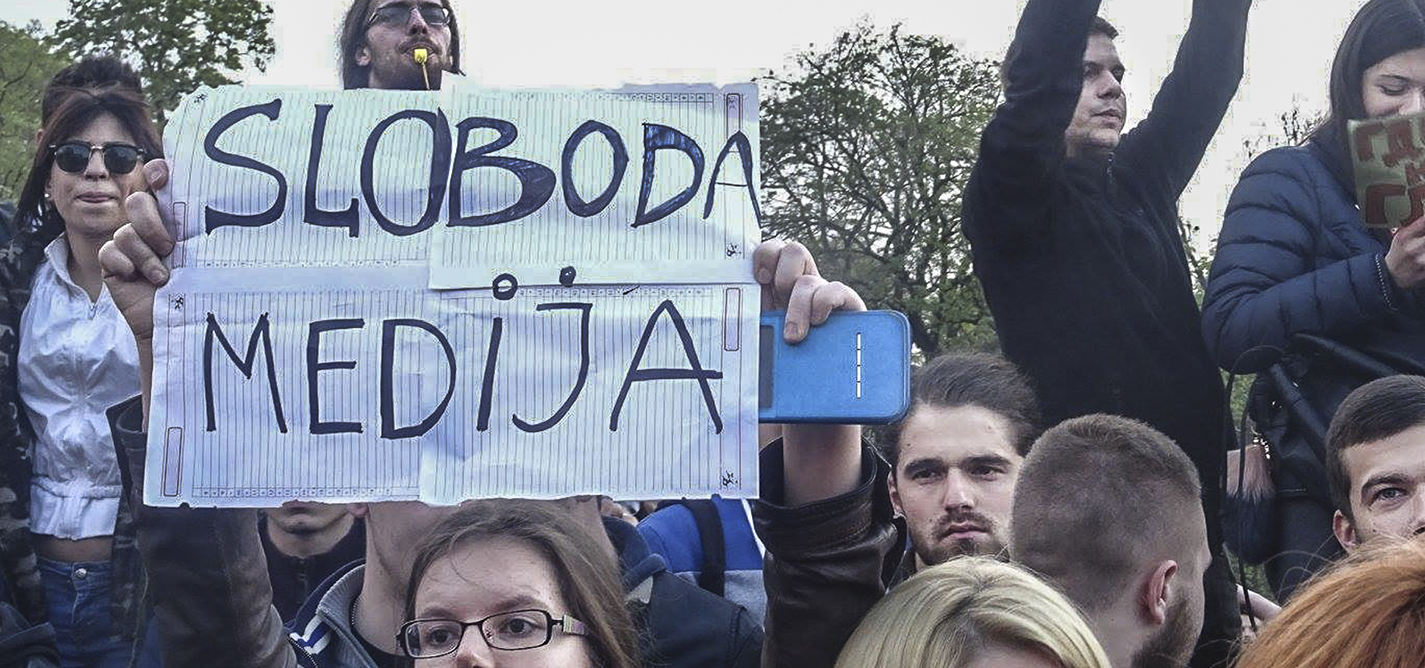

There is a media blackout in the ‘stabilocracy’

Creating a rosy media image of Serbia under the watchful eye of Aleksandar Vucic.

The propaganda-advertising program is working like a drugstore: 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.

“Anybody who wants to engage in politics or criticize and address the control of the government, even only to objectively report to the public about what is going on, is existentially threatened and at permanent risk of losing their job."

Isadora Petrovic, editor of the Serbian Edition of Le Monde Diplomatique.Journalists in Serbia still have the statement of Johannes Hahn, the EU Commissioner for enlargement, ringing in their ears. In 2015, Hahn declared that “proof is needed for the claim that the freedom of media is threatened.”

Sasa Dragojlo

Sasa Dragojlo is journalist for Insider, the investigative Serbian media that is well known for its stories on corruption, crime, hooligans and extremist groups. He has previously published for media including BIRN, Akuzativ, Masina, Bilten, Vice, Lice Ulice, Vreme, Danas, Tacno.net and Identitet.

DISCLAIMERThe views of the writer do not necessarily reflect the views of Kosovo 2.0.

This story was originally written in Serbian.