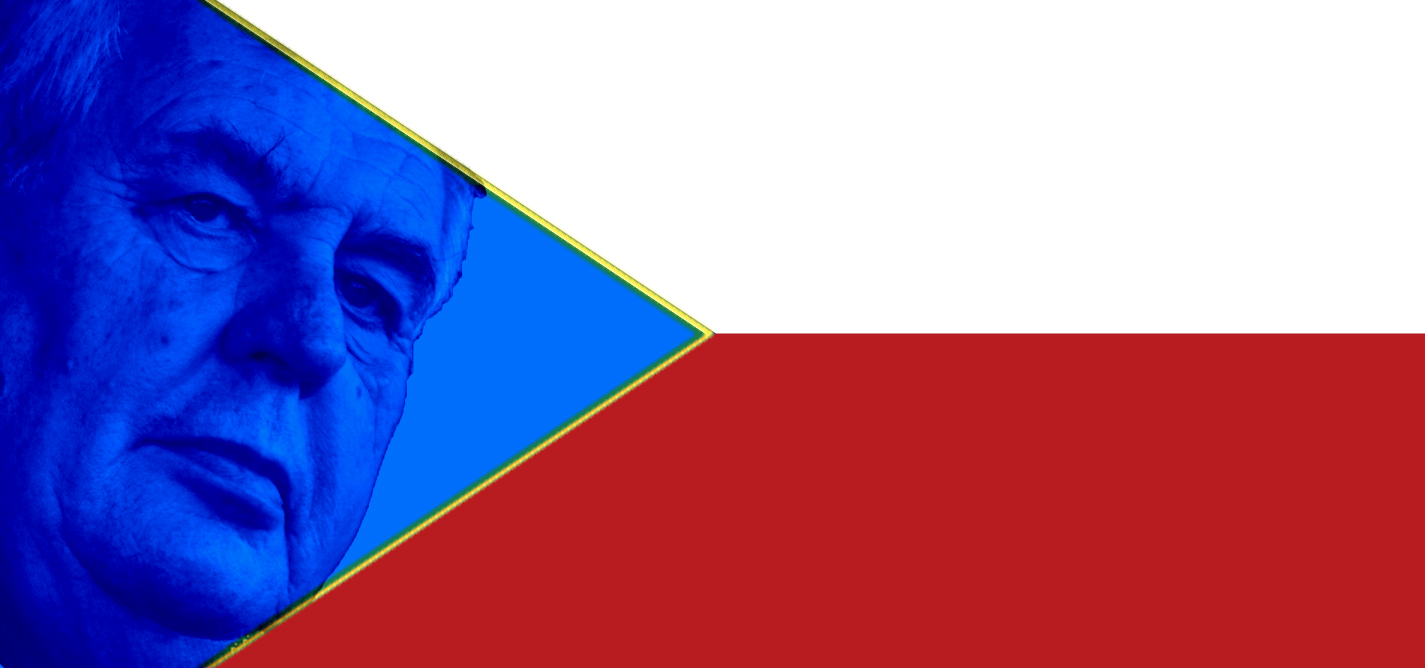

Miloš Zeman’s election victory in Czech Republic could spell bad news for Kosovo

Stagnant Czech-Kosovar relations look set to continue.

This precarious dynamic could be at risk.

“Kosovo representatives should be ready to publicly make the case for Kosovo when the situation demands it.”

Tomáš Dopita, Dec. 2017

Eraldin Fazliu

Eraldin Fazliu is a former journalist at Kosovo 2.0. Eraldin completed his Master’s on ‘European Politics’ at the Masaryk University in the Czech Republic in 2014. Through his studies Eraldin became interested in the EU’s external policies, particularly in promotion of the rule of law externally. He is a passionate reader of politics and modern history.

DISCLAIMERThe views of the writer do not necessarily reflect the views of Kosovo 2.0.

This story was originally written in English.