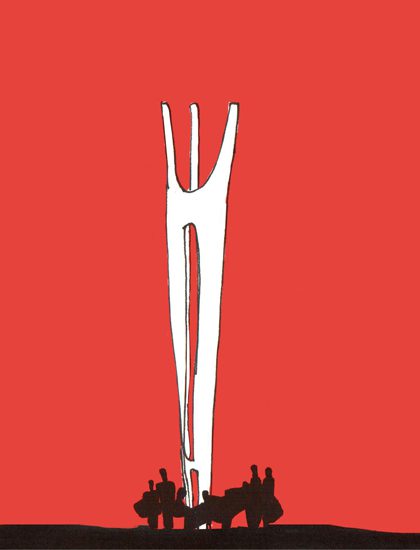

Monuments without a home

Symbols of Yugoslavia are left to decay in today's world

I dream of a Europe without monuments, that is, without monuments of death and destruction. Perhaps monuments to love, to joy, jokes and laughter.

Bogdan Bogdanovic

Vesa Sahatçiu

Vesa Sahatciu completed her master’s in Contemporary Art Theory at Goldsmiths, University of London. She worked for the National Gallery of Kosovo and as a columnist for the Express daily, and as an occasional contributor to the weekly Java.

This story was originally written in English.