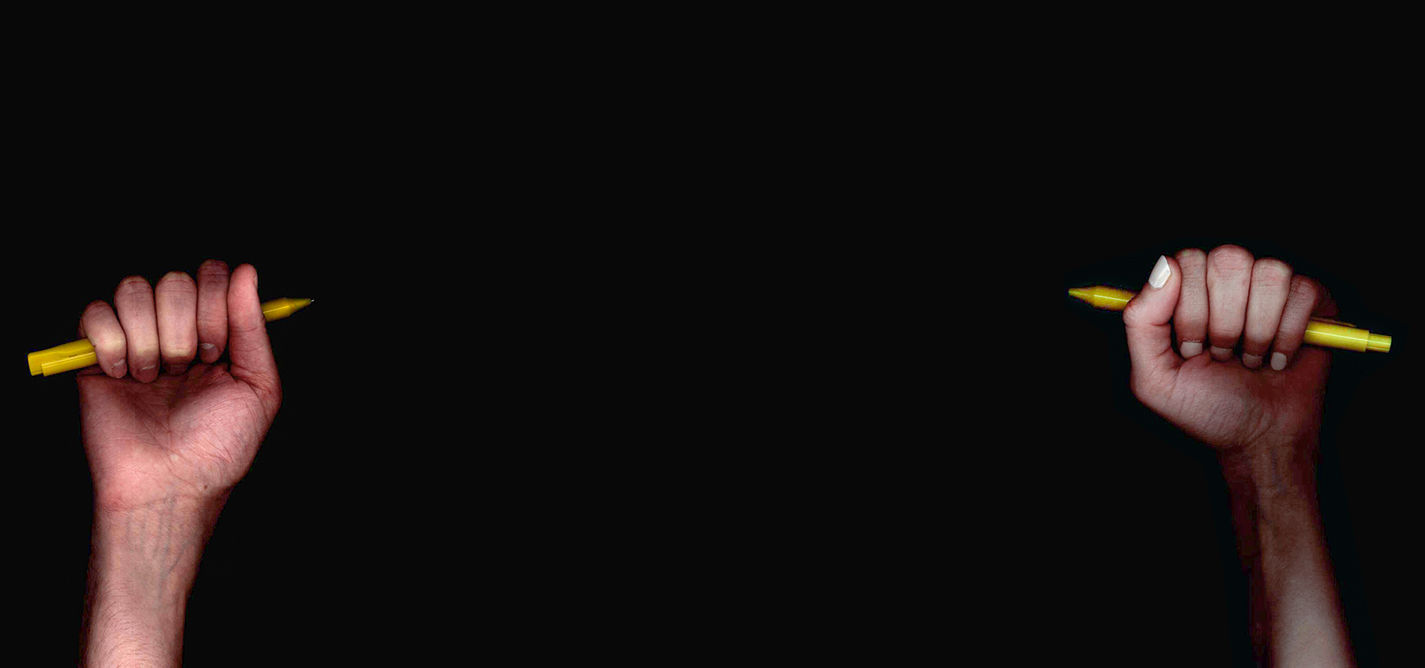

Press freedoms in decline

Regional media targeted by politicians frantically struggling to survive.

Nedim Sejdinovic, the president of the Independent Association of Journalists of Vojvodina, who has been exposed to constant attacks, believes that the media situation in Serbia is worse than under Slobodan Milosevic’s regime.

“Today, Albania doesn’t have any media, but does have offices that multiply propaganda offered by political parties.”

"It is difficult to talk about media freedoms and independent journalism. We can only talk about the bitter struggle for survival.”

Davor Konjikusic

Davor Konjikusic is a journalist and visual artist from Zagreb, Croatia. He studied journalism at the Faculty of political sciences in Belgrade and photography at the Academy of Dramatic Art in Zagreb. He also works as a lecturer and researcher.

This story was originally written in Serbian.