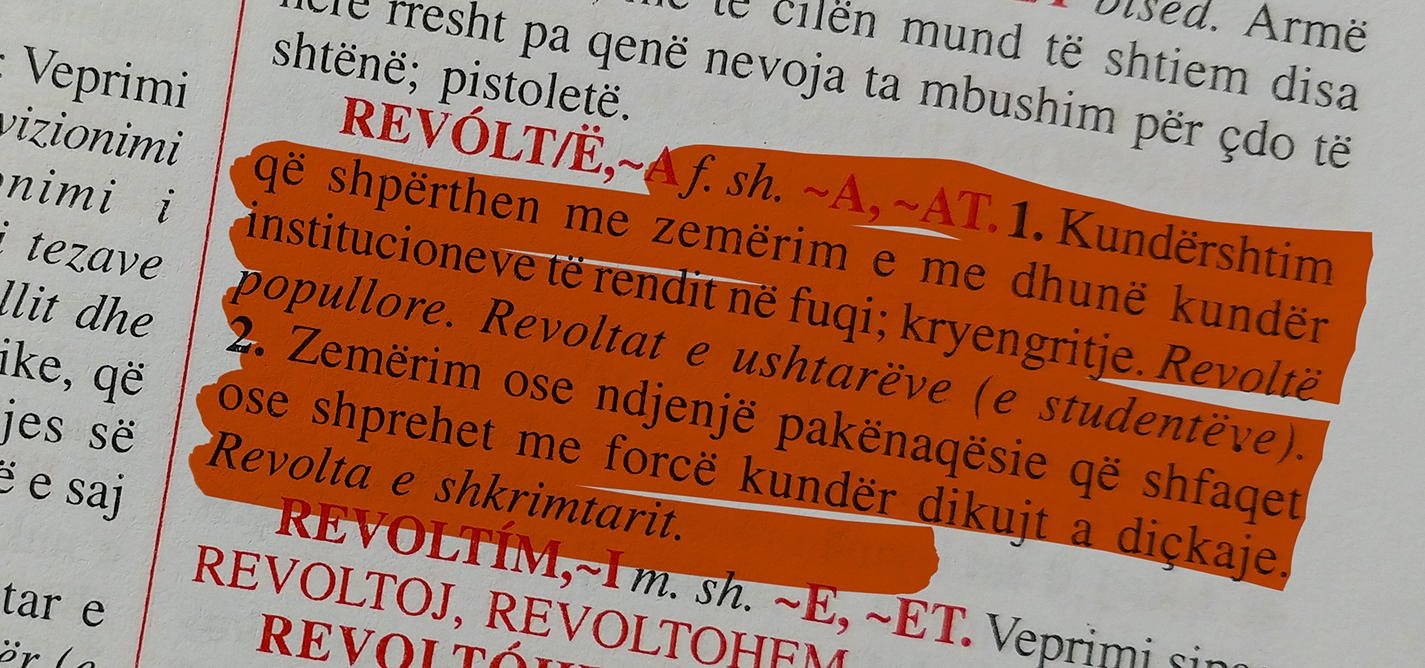

Revolt, not “inat”

A reaction to Besa Luci's editorial on the necessity of dealing with the “inat” over the Special Court.

Let’s teach people afflicted by ‘inat’ that justice is apolitical, it is a right of the victim. Understanding their inat, and caressing them to sleep.

Phrases that speak of the Adem Jashari - Ibrahim Rugova binary and about how pacifism and resistance are complementary do not reach the core of pain and trauma.

Zgjim Hyseni

Zgjim Hyseni is the deputy president of the Social Democratic Party of Kosovo. He graduated from the Law Faculty of the University of Prishtina and has been politically active since 2005. He was previously a member of the Vetëvendosje presidency and leader of the Secretariat for Ideo-Political Formation.

This story was originally written in Albanian.