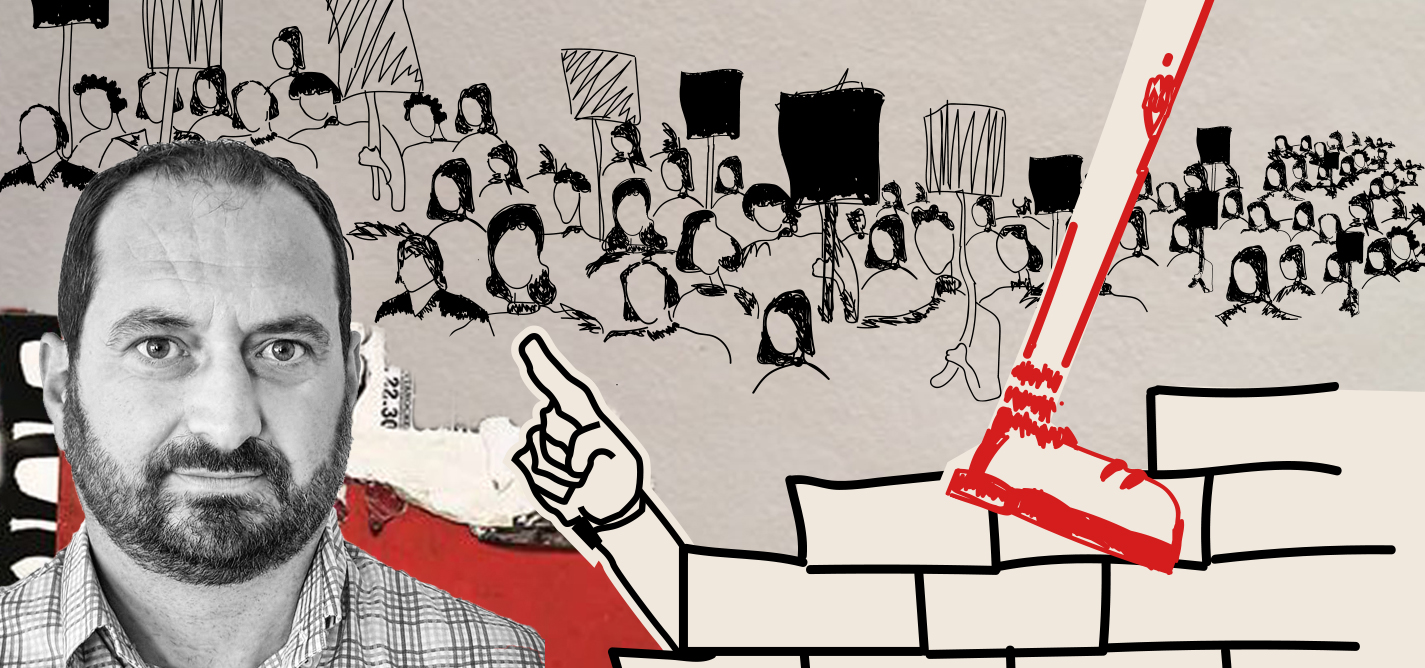

Roland Gjoni: Kosovo is simultaneously ‘too big’ and ‘too small’ of an international issue

Legal and political scientist talks geopolitics, Albanian nationalism and domestic tensions in Albania.

Albanian nationalism is generally reactive and not proactive, largely mobilized in response to shifting geopolitical power configurations.

While most people recognize the fact that the status quo and a frozen conflict are dangerous, it does not automatically follow that any move beyond the status quo is positive.

For Serbia, the land swap is not the final and definite solution for Kosovo, but another step in the process of further diluting Kosovo’s statehood.

It is true that if land swaps take place, the principle of inviolability of borders cannot be sustained and Kosovo’s statehood as declared in 2008 will be seriously questioned.

If for some reason Kosovo agrees to the territorial exchange under international pressure, its implementation on the ground will be very difficult due to the lack of popular support.

Instead of opening the way to political change, the protests showed the limits of transforming social resentment and disappointment into meaningful political alternatives.

Fitim Salihu

Fitim Salihu is a former K2.0 staff journalist, covering mainly politics and governance. Fitim has a bachelor’s degree in political science from the University of Prishtina.

This story was originally written in English.