Squash online hate speech

Digital spaces exclude vulnerable groups.

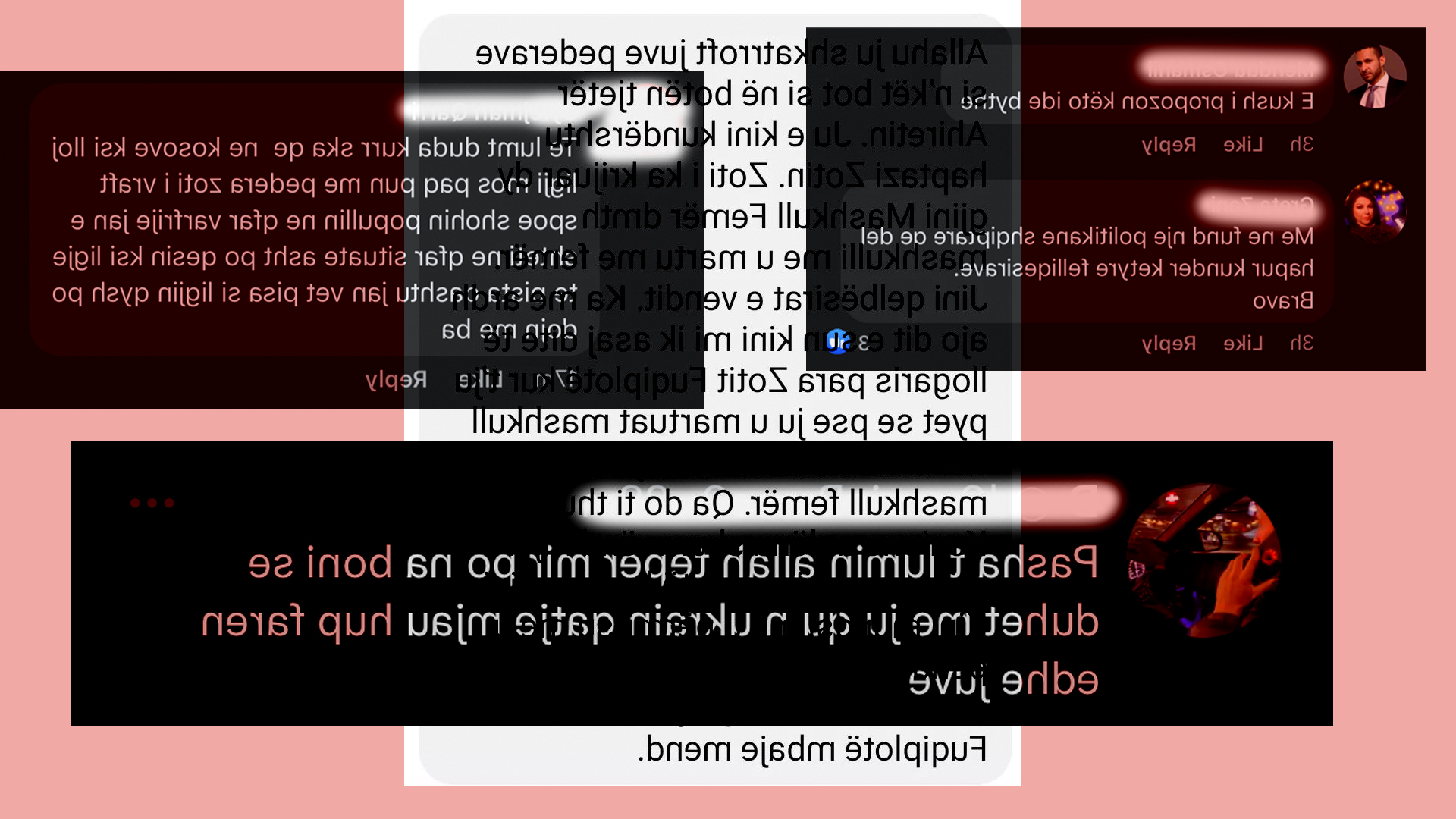

Online hate speech targets outspoken women and LGBT people.

If we want genuine democratic public spaces in the digital sphere, it is our duty and responsibility to cultivate safety in those spaces.

Shqipe Gjocaj

Shqipe Gjocaj is a feminist activist, gender specialist, and an independent journalist. She is a regular contributor to Prishtina Insight where she writes on gender issues and human rights. Her articles have also been published in Kosovo2.0, sbunker, and Reuters. Shqipe Gjocaj works with non-governmental organizations on projects related to the same issues. In 2017, she took part in the Balkan Fellowship for Journalistic Excellence. Shqipe is a K2.0 Human Rights Journalism Fellowship program fellow (2019 cycle).

DISCLAIMERThe views of the writer do not necessarily reflect the views of Kosovo 2.0.

This story was originally written in Albanian.