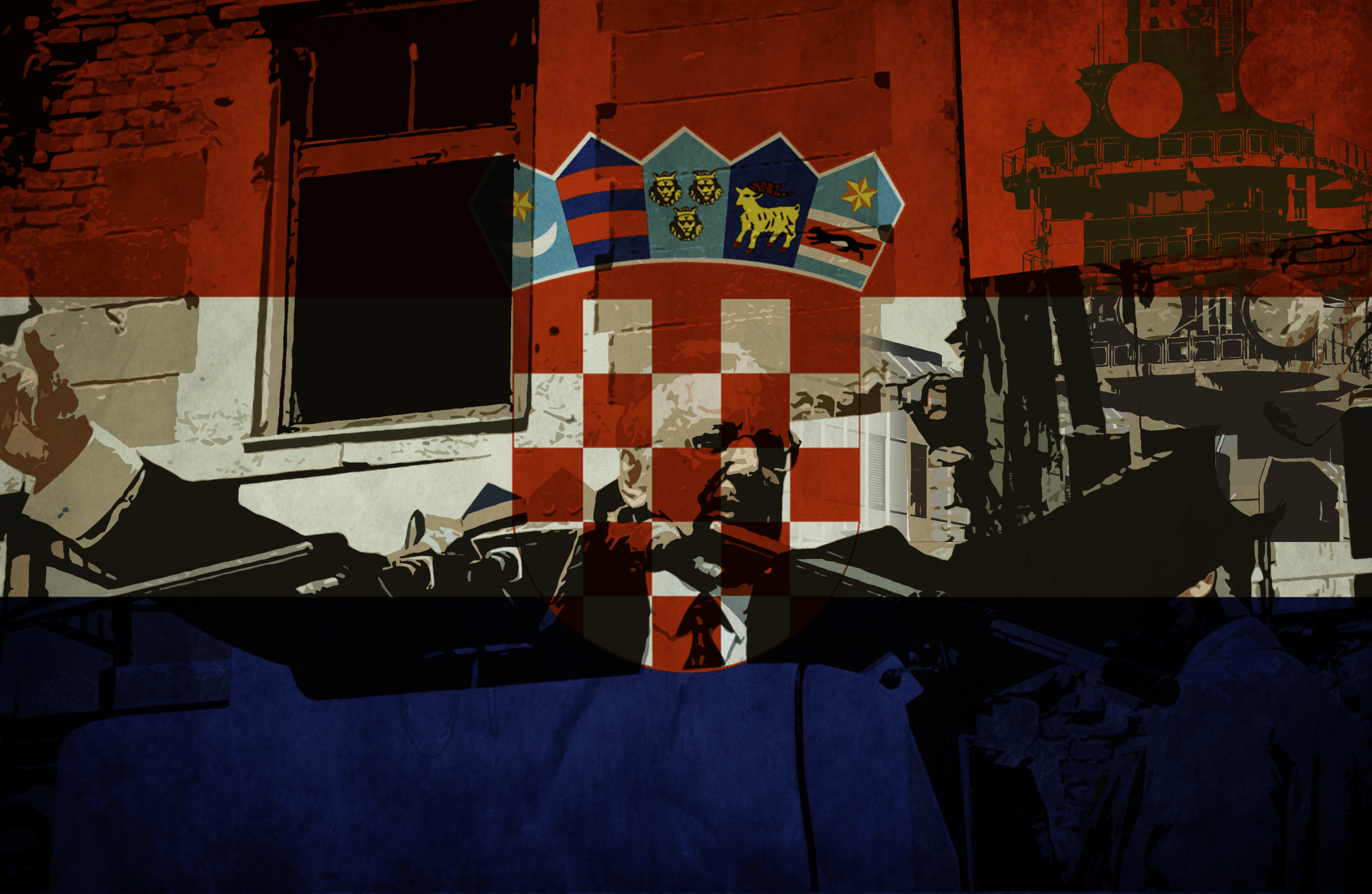

The Croatian state tolerates and abets historical revisionism

An honest assessment of the past is needed for building sustainable peace.

No new regime has taken decisive steps to confront the past.

Historical revisionism becomes particularly problematic when it is promoted by state institutions.

This mockery of the victims aired in an afternoon entertainment-informational program on national television.

In other words, the fascist salute is considered permissible to use if it is related to the Croatian War of Independence.

Tia Glavocic

Tia Glavočić was born in Dubrovnik, where she completed gymnasium. She graduated from the Faculty of Political Science and the Faculty of Philosophy. Currently based in Zagreb, she works at Documenta — Center for Dealing with the Past. Her research interests include political violence and culture of remembrance, with a particular focus on World War II.

DISCLAIMERThe views of the writer do not necessarily reflect the views of Kosovo 2.0.

This story was originally written in English.