The pandemic in the shadow of discrimination

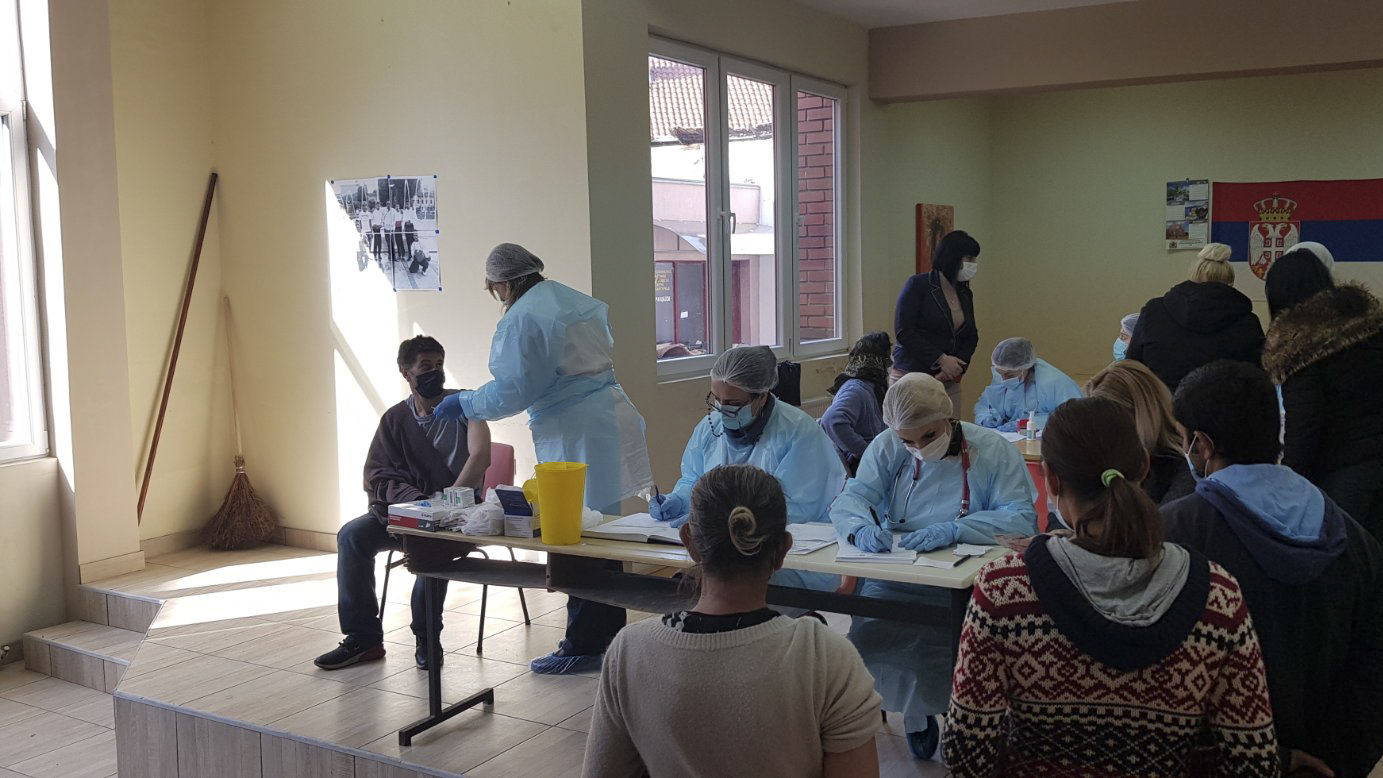

The region’s Roma seek more information on COVID-19 vaccination.

The region's public institutions have barely done anything to inform the Roma about the importance of protection and vaccination.

As in other parts of B&H, the Brčko district also suffers from a lack of information on vaccination in the Roma language.

Although the state did get involved, the main distributors of information on vaccination in North Macedonia remain Romani media and NGOs.

Dalibor Tanić

Dalibor Tanić is a journalist and activist. He runs the website Udar, dedicated to issues related to the lives of Roma communities. Surrounded by young Roma people, he is building the platform for the new generation. As a journalist, he has published for various media, including the online magazine Žurnal in Bosnia, and he has won awards for his investigative journalism work.

This story was originally written in Serbian.