The struggle for cultural space

Is festivalization leaving independent culture to starve?

Critics argue that festivals tend to attract a significant proportion of cultural budgets, often at the expense of supporting ongoing cultural production by independent artists.

“A festival takes place once a year, no matter its high or low quality.”

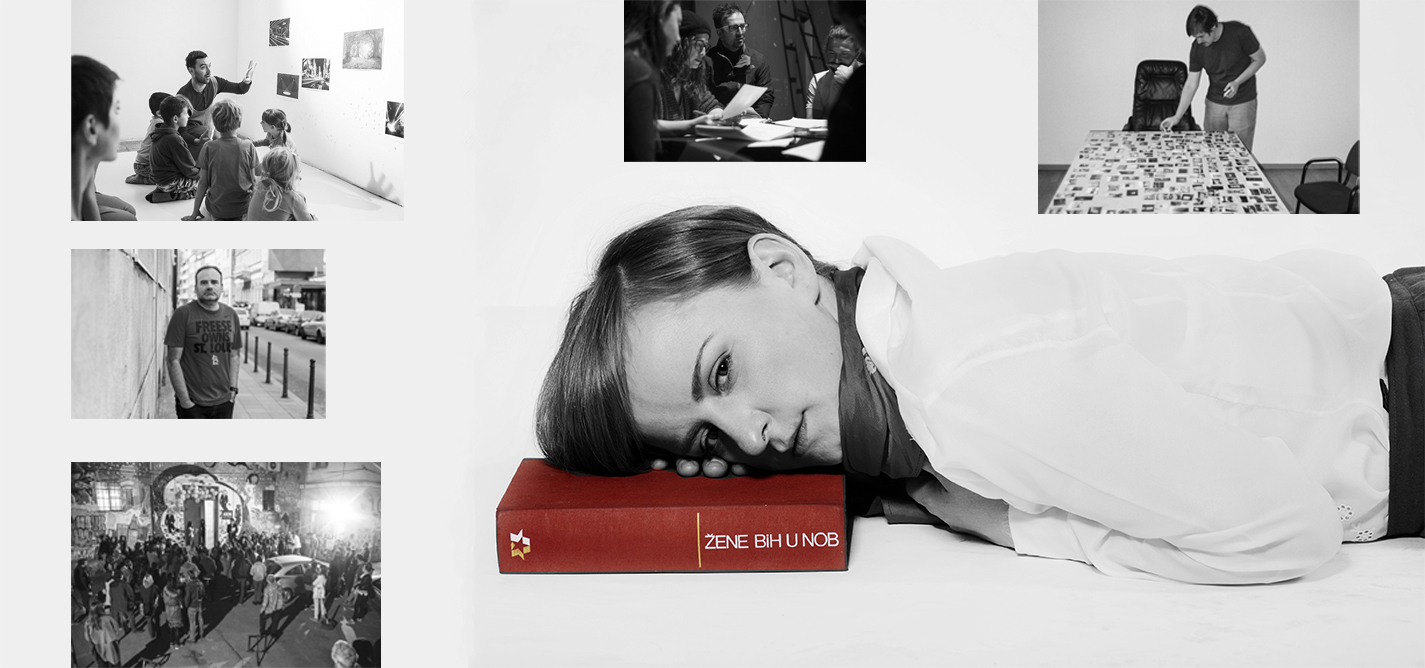

Adela Jušić, contemporary visual artist"Festivals [should] have a mission of waking us up, leading us to doubt, critically observing reality.”

Nikola Vucic

Nikola Vučić lives in Sarajevo where he works for a regional TV news channel. His topics of interest include culture, human rights, ideology and politics. He has been awarded with two journalistic awards for his stories on gender-based discrimination in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

This story was originally written in Serbian.