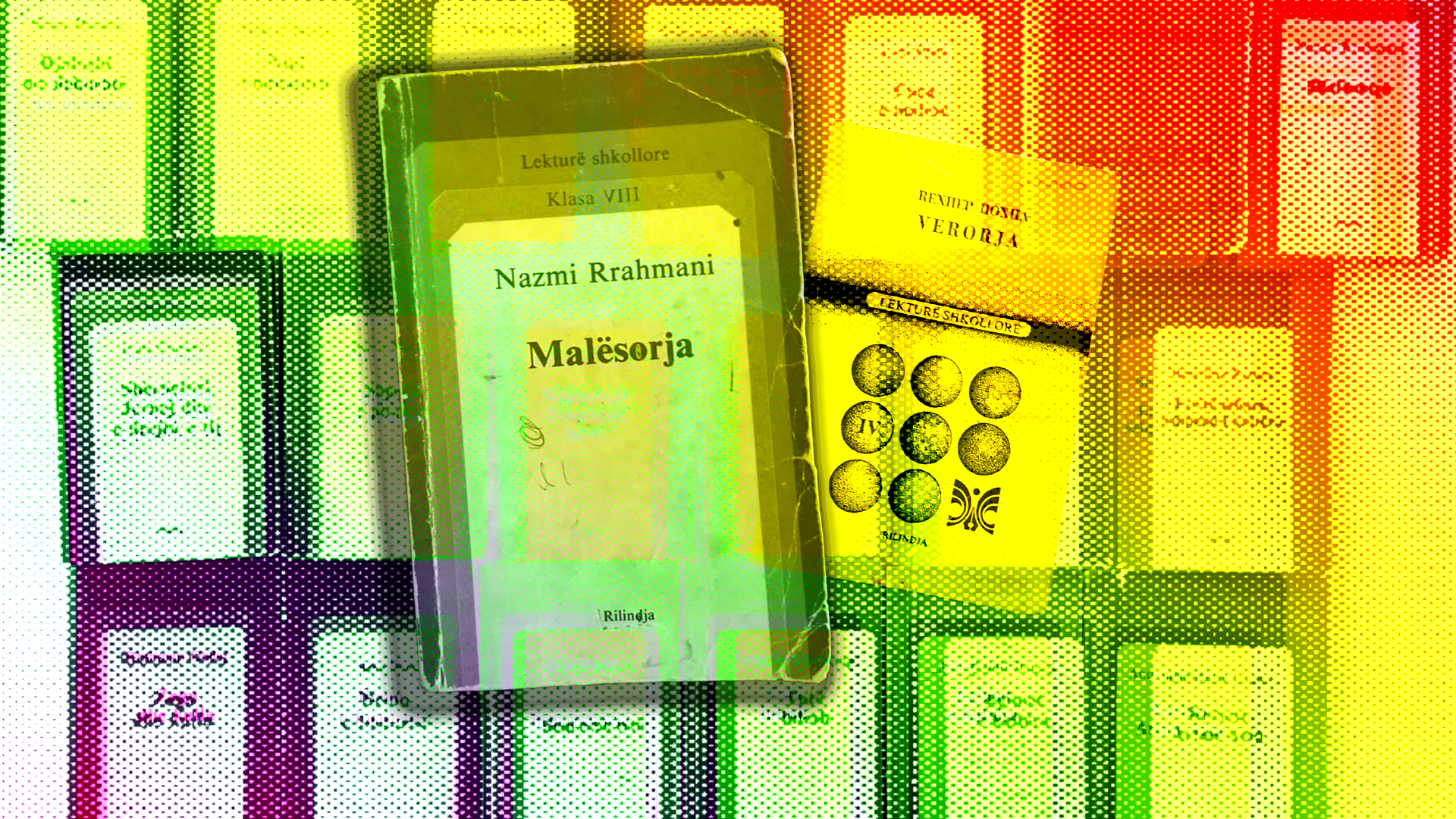

The “unaltered” literature of Kosovar schools

Literature in schools reproduces derogatory and racist language without critical examination.

&|11.09.2025

|

Student Reading Statistics

School is not a museum, and textbooks and school readings are not artifacts frozen in time or untouched by interpretation.

Uranela Demaj

Uranela Demaj is a Professor of Sociolinguistics and former vice rector for science and research at AAB College in Pristina, Kosovo.

Agon Ahmeti

Agon Ahmeti is a professional with over ten years of experience in civil society, education and culture. He has founded and led initiatives such as the NGO ETEA, the Center for Education and Culture “Libart,” the Children’s Book Festival and Fair, and the Circulating Library with a focus on advancing education, civic participation and cultural enrichment.

DISCLAIMERThe views of the writer do not necessarily reflect the views of Kosovo 2.0.

This story was originally written in Albanian.