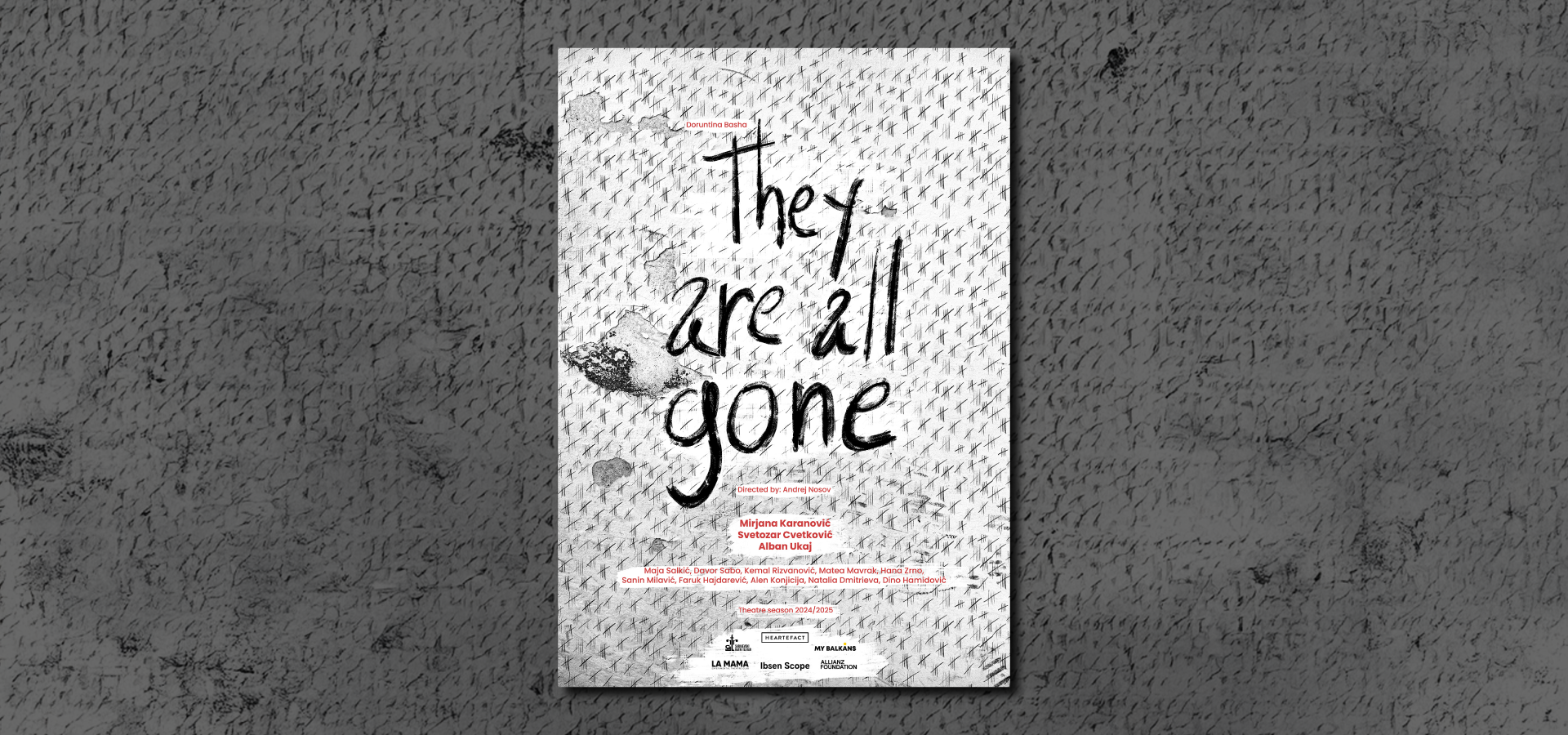

“They Are All Gone” — The unbearable loneliness of those left behind

A stage interpretation exploring the memories and lives of war survivors.

|25.07.2025

|

Caption: Photo by Nebojša Babić for Heartefact, still from the play “They Are All Gone”

Photo by Nebojša Babić for Heartefact, still from the play “They Are All Gone”

The living room is transformed into a gallery of relics, a private museum curated by longing.

Photo by Nebojša Babić for Heartefact, still from the play “They Are All Gone”

Sadika bathes in ice water because that is how her children died. She drinks water dirtied by soil because it brings her closer to those who have passed.

Dhurata Hoti

Dhurata Hoti is a writer, playwright, and screenwriter from Kosovo. She has written plays, film scripts, short stories, and reviews.

This story was originally written in Albanian.