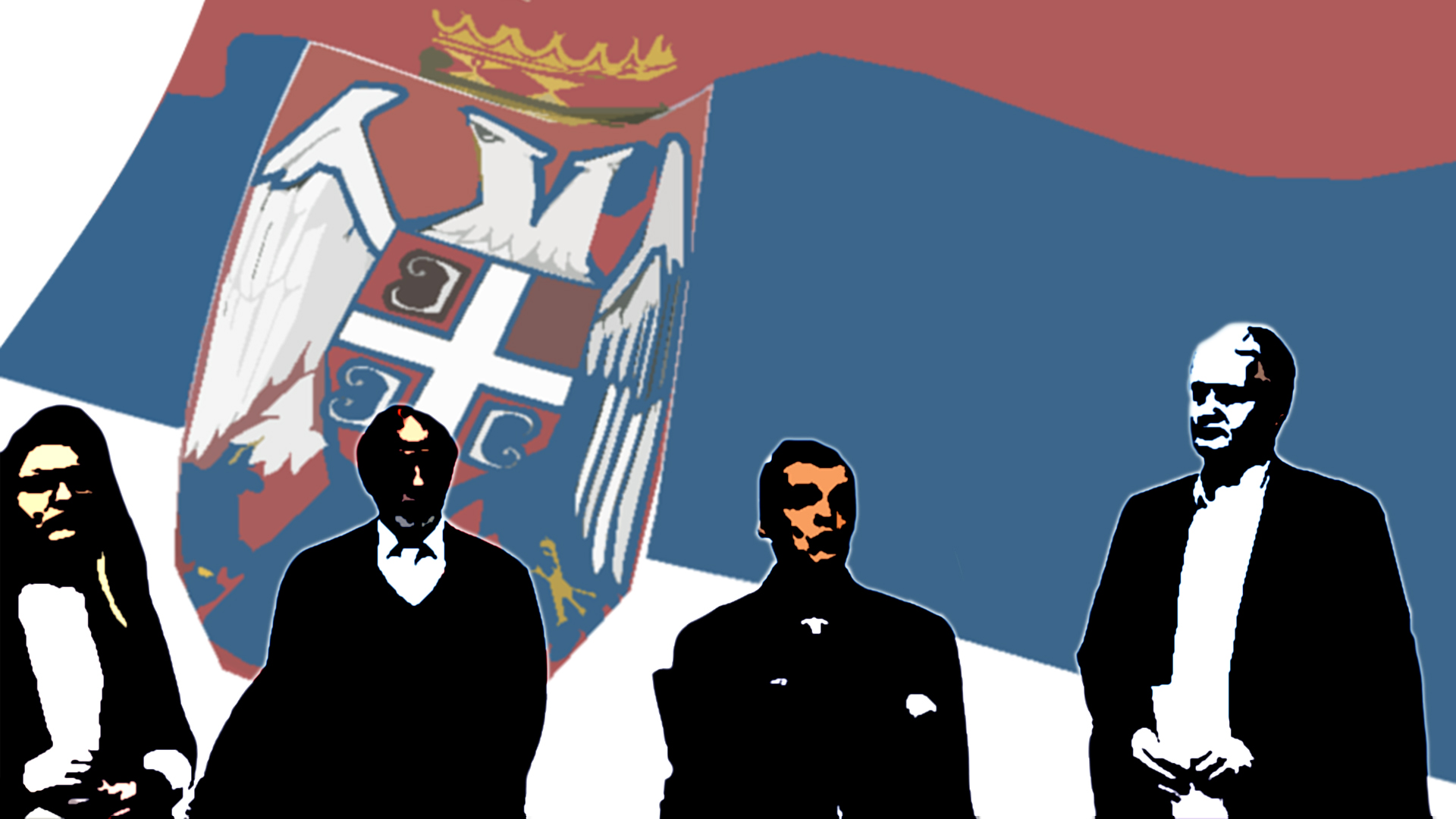

Vučić’s favored opposition

Serbia's ultra-right has the media and invasion of Ukraine to thank.

The pro-Russian rhetoric would not have reached a large number of voters if not for the media under Vučić's control.

The friendly media treatment during the campaign also supports the argument that Vučić is artificially pumping up the right-wing opposition.

Dario Hajrić

Dario Hajrić writes opinion pieces and analyses on the topics of social power, violence, the political class and the media. He cooperates with Deutsche Welle and the portal Remarker.

DISCLAIMERThe views of the writer do not necessarily reflect the views of Kosovo 2.0.

This story was originally written in Serbian.