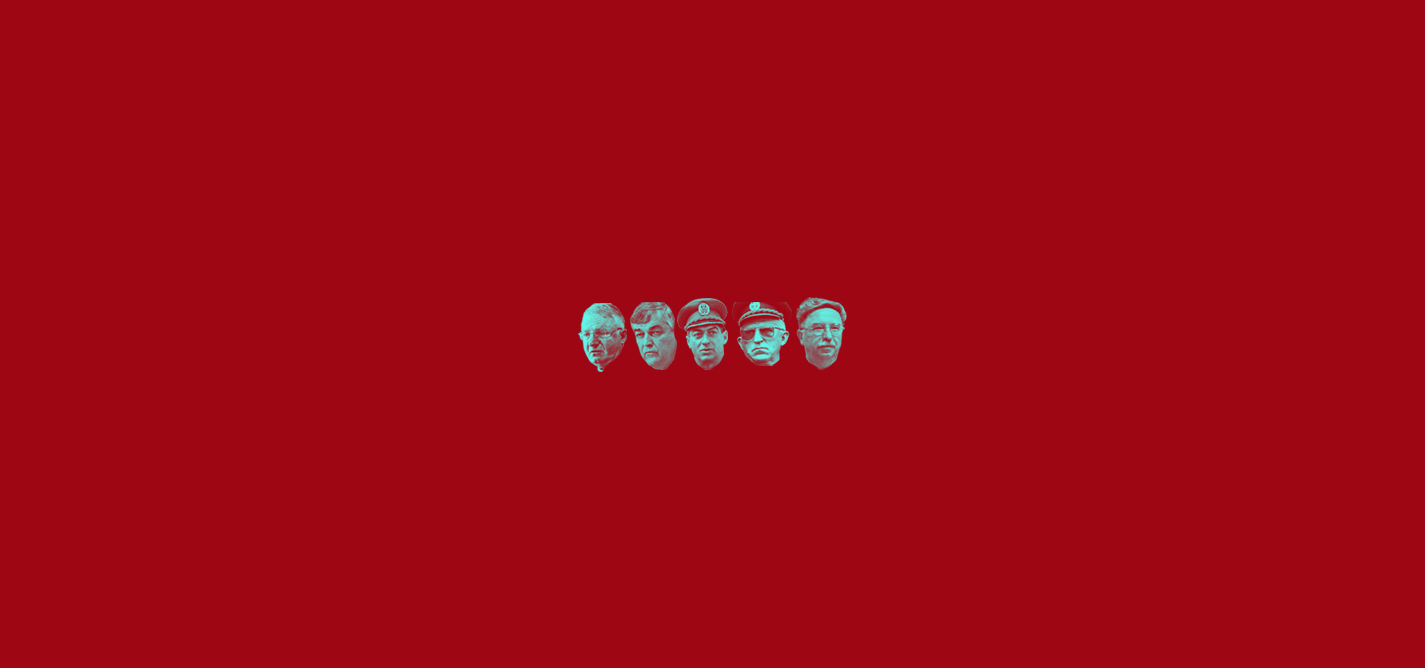

The war is over, but war criminals remain

Serbia has never cleaned up its army and police from compromised war personnel.

Bozidar Delic, ex commander of the 549th Brigade of the VJ, in whose area of responsibility in Kosovo around 2,200 civilians were killed, including a large number of them murdered in military actions, is today a deputy in the Parliament of Serbia, as a member of the Serbian Radical Party.

Vucic has never given a clear stance toward his war past, claiming that his calls to conflict were taken out of context, or that he never even said them.

Nemanja Stjepanovic

Nemanja Stjepanovic is a journalist from Belgrade who previously worked for years for the news agency Sense, specialising in reporting on war crimes proceedings in front of the ICTY. Since 2016 he has worked for the Humanitarian Law Center in Belgrade. He occasionally writes for the portal Pescanik and the daily Danas.

DISCLAIMERThe views of the writer do not necessarily reflect the views of Kosovo 2.0.

This story was originally written in Serbian.