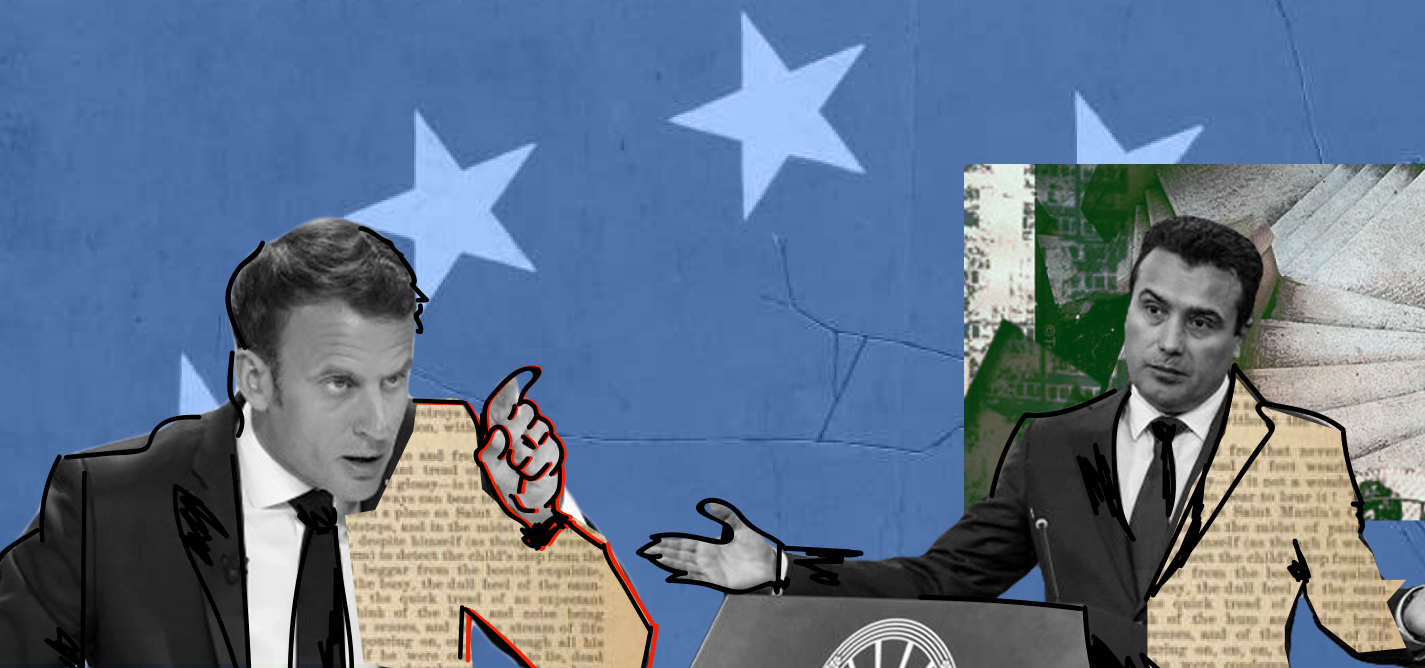

What next after Macron’s rejection of North Macedonia?

Delaying the start of EU negotiations will introduce a new turbulent era.

In the last 11 years, Macedonia has been receiving instructions and clear messages that its European and Atlantic integration are impossible without a deal with Greece.

“We, as a state aspiring to EU membership, should carry on moving the European road, because one day Macron’s attitude will change.”

Ismet Ramadani, analyst.For VMRO-DPMNE, this situation is a new chance to take over the government once again.

Biljana Sekulovska

Biljana Sekulovska worked at A1 TV – Makedonija between 1993 and 2011, including as a correspondent from Washington DC and Brussels. From 2000 to 2010 she was also a weekly columnist with the daily Vesti. In 2013 she established the video news Portal NOVA TV with a group of colleagues.

DISCLAIMERThe views of the writer do not necessarily reflect the views of Kosovo 2.0.

This story was originally written in Serbian.