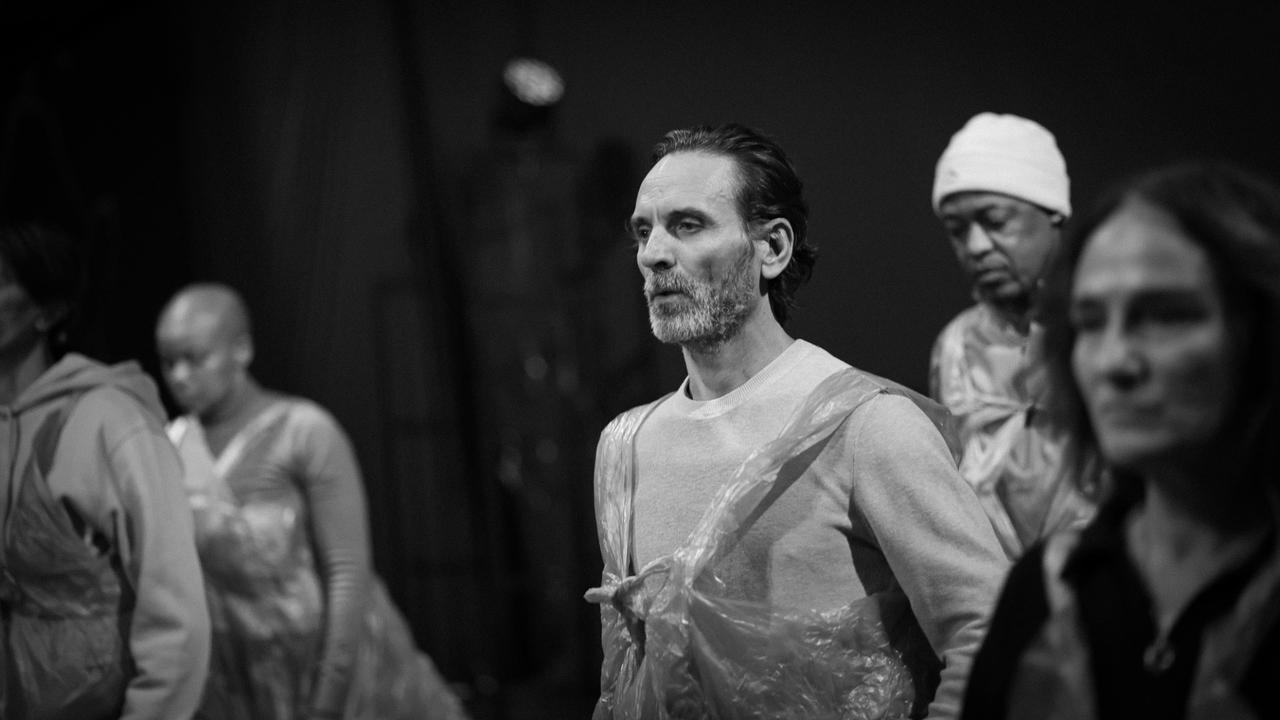

When Anton Çetta met Desmond Tutu

A play questioning forgiveness without justice.

|16.10.2025

|

“The true Albanian was once the one who took revenge. We made forgiveness an act of bravery," says Don Lush Gjergji.

Both trees offer shade, but not shelter from memory.

Agron Demi

Agron Demi is a civil society activist and the founder and executive director of the Atlas Institute.

This story was originally written in English.