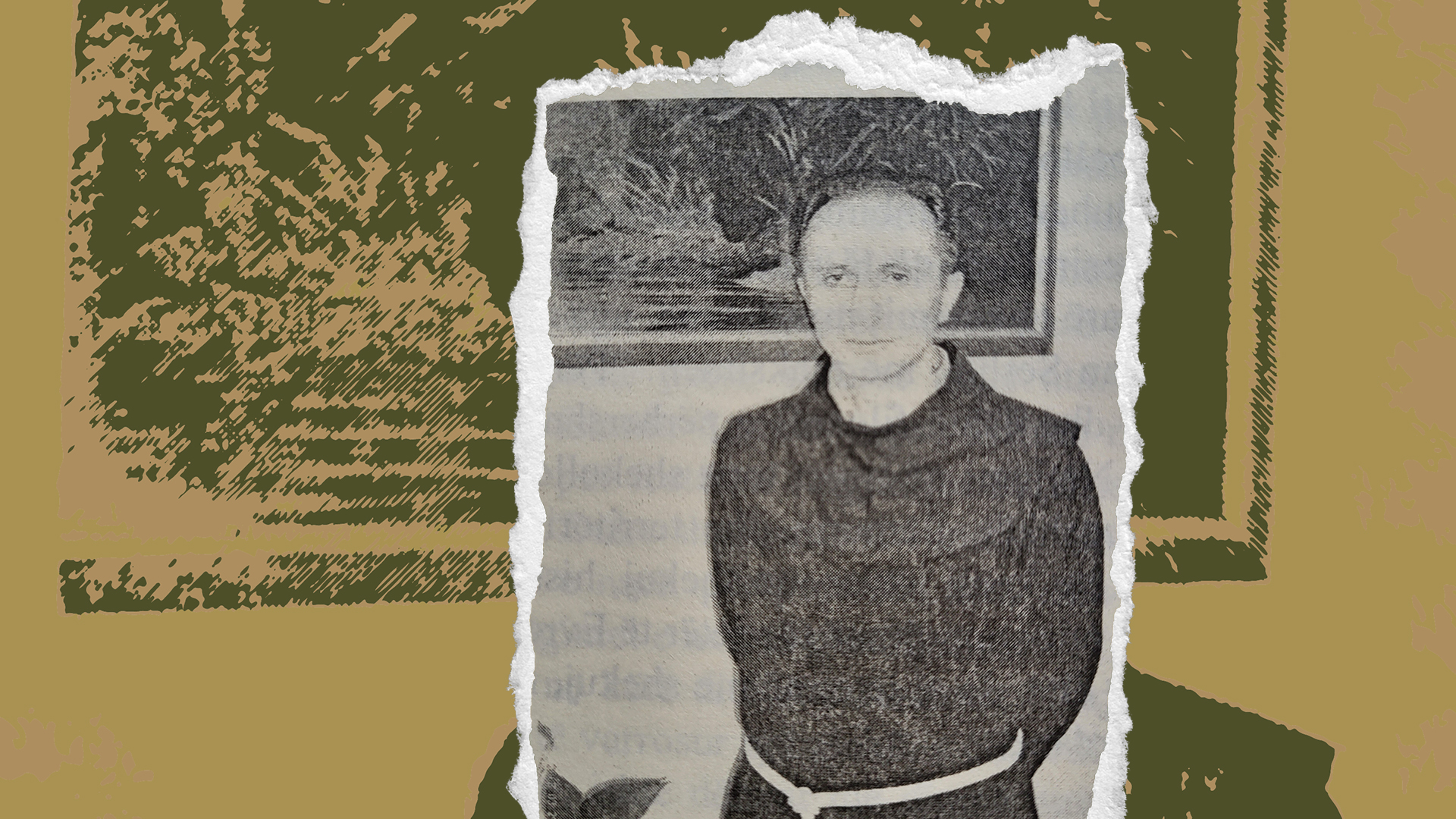

An extraordinary war hero

Between prayer and war — the story of Father Marjan Lorenci

|23.05.2025

Shkëlzen Gashi

Shkëlzen Gashi studied Political Sciences at the University of Prishtina and Democracy and Human Rights on the joint study programme of the Universities of Bologna and Sarajevo for his Master’s degree. He is author of many publications (books and articles). In 2010 he published the unauthorized biography of Adem Demaçi (available in English), who had spent 28 years in Yugoslav prisons. Recently, he has published many articles about the presentation of the history of Kosovo in the history schoolbooks in Kosovo, Albania, Serbia, Montenegro and Macedonia. Also, he is writing a biography on Ibrahim Rugova, the leader of the Albanians in Kosovo from 1989–2006.

This story was originally written in Albanian.