"The Ottoman Empire" volume excludes Skanderbeg's uprisings

"Joint History Project": a five-part critique of (mis)representation of Albanians in alternative history books.

The volume should go further and present the real motives of the rebellions led by Skanderbeg, which were mainly religious and proprietary in nature.

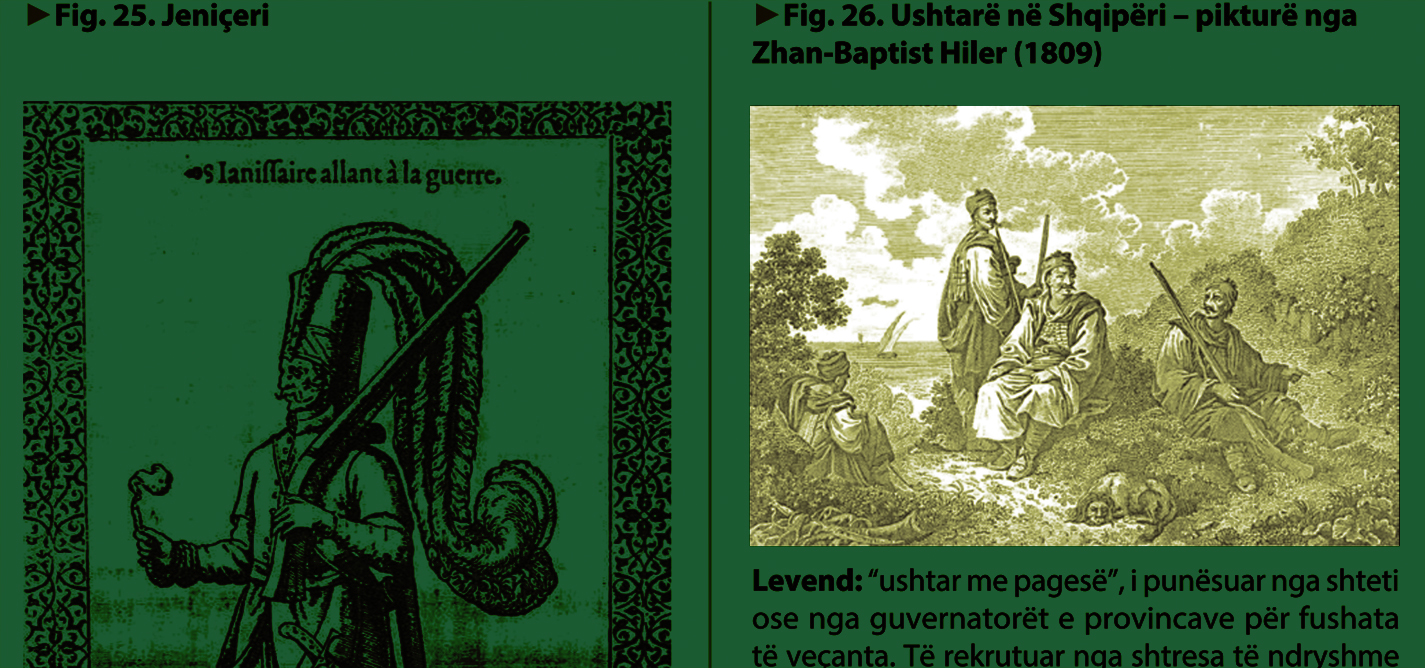

Devshirme was a systematic method of forcibly recruiting young boys: A child would usually be taken from one in 40 houses, sent to Istanbul, converted, taught Turkish, and trained as a soldier.

The last subchapter offers a short but scandalous fragment about Albanian women, where they are presented as uneducated, speaking no language other than their mother tongue.

A series of Albanian rebellions broke out, which were not calling for autonomy and national liberation, but were against recruitment, western-style uniforms, new taxes, disarmament of the population, and so on, are not mentioned in this volume.

Summary of exclusions

Shkëlzen Gashi

Shkëlzen Gashi studied Political Sciences at the University of Prishtina and Democracy and Human Rights on the joint study programme of the Universities of Bologna and Sarajevo for his Master’s degree. He is author of many publications (books and articles). In 2010 he published the unauthorized biography of Adem Demaçi (available in English), who had spent 28 years in Yugoslav prisons. Recently, he has published many articles about the presentation of the history of Kosovo in the history schoolbooks in Kosovo, Albania, Serbia, Montenegro and Macedonia. Also, he is writing a biography on Ibrahim Rugova, the leader of the Albanians in Kosovo from 1989–2006.

This story was originally written in Albanian.