In-depth | Politics

A year of institutional deadlock, unlocked in minutes

MPs vote to form the Kurti III government.

12.02.2026

In-depth

More

Citizens pay the cost of flooding

From damage to homes and businesses to insufficient compensation.

Perspectives

More

Longform

More

Videos

More

Recommended

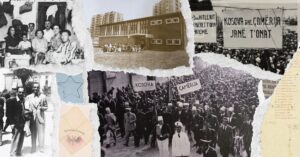

In photos: The history of Trepça through crystals

The Crystal Museum in Stan Terg preserves the rich heritage of Trepça.

Podcasts

More

Trending

Best Bits

Subscribe to Best Bits and receive our best content of the week.

Donate

Help us bring you the journalism you count on. All amounts are appreciated

Photostories

Explore more