It was 2006. We were just a few meters from the Hungarian border with Serbia. The closer we got, the more tense my parents became. Would we be allowed to cross the border, or would we be turned back and forced to take a detour through Croatia and Montenegro?

It was our turn, and the policeman asked us a few questions, which our parents answered in Serbian. I only recognized the Serbian word for the city of Peja and assumed he was asking where we were headed. He looked at my father, mother, brother, and me in turn, calling out each of our names, including mine, in a cold tone. Then he handed back our passports, gestured toward Serbia, and we continued on our way.

We drove through Serbia for several hours until we reached Merdare, the border between Serbia and Kosovo, where an Albanian policeman greeted us with, “Welcome, are you tired?”

Our parents were both relieved and slightly suspicious that we had crossed Serbia without any issues. My father said that with our German passports, we were now untouchable.

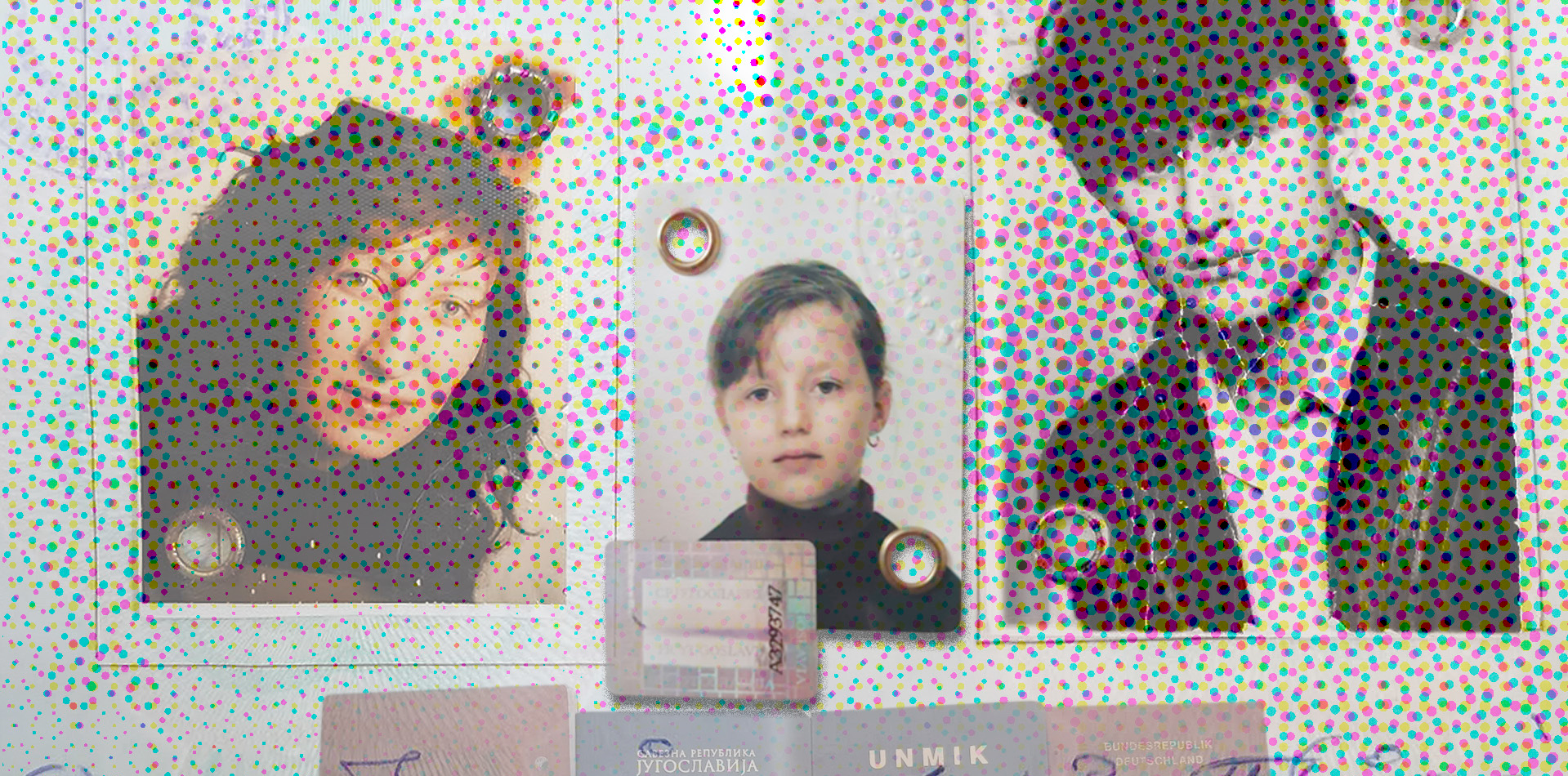

I obtained German citizenship that year, more than 10 years after having been born and raised in Germany. Before that, my life was marked by a series of documents, each bearing my name but assigning me a different legal status. The color of each piece of paper dictated our daily lives: where we could live, and how far we were allowed to move.

Duldung (temporary suspension of deportation) was our first status. It allowed us to remain in Germany, but we were not permitted to leave our city, Braunschweig. After several months of extensions, in 1995, we received a residence permit, which finally allowed us to travel beyond the city limits.

With each new status, our perimeter expanded. But with every new document, I found myself questioning where I truly belonged: in Germany or in Kosovo? I was born in Germany, but I wasn’t from there. My parents came from Kosovo, but I wasn’t from Kosovo either.

My parents came to Germany in 1993, a year before I was born. While living in Prishtina, they were both students; my mother studied economics, and my father studied law. They lived together as an affianced couple

Prishtina, like the rest of Kosovo, was becoming increasingly unsafe for Kosovar Albanians. In 1989, Kosovo’s autonomy as a province within the former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia was abolished, marking the beginning of a sharp escalation in the repression of Albanians — arrests, beatings, and even killings became part of daily life.

At the same time, resistance movements emerged, particularly through student-led protests, in which my parents also took part. Persecuted and increasingly unsafe, they were eventually forced to leave Kosovo for Germany. My father left first, followed by my mother a few months later.

They chose Germany — a country that both of my grandfathers had helped rebuild in the 1970s as Gastarbeiter (guest workers) after the devastation of World War II. Between 1955 and 1973, around 14 million guest workers arrived in West Germany through government recruitment programs to support the country’s postwar recovery.

As soon as they arrived in Germany, my parents began making regular visits to the German authorities. The first step was registering with the foreigners’ office — Ausländerbehörde. At the immigration office, they had to recount their lives and express their deepest fears in a language they barely understood: Warum sind Sie in Deutschland? — Why are you in Germany?

Today, I wonder how anyone can explain the indescribable in a foreign language — war, oppression — knowing that the person on the other side of the counter will most likely never truly understand. After all, their only connection to Yugoslavia may well have been summer holidays on the beautiful Croatian or Montenegrin coast.

The situation in Kosovo and the successive wars in the former Yugoslavia offered no guarantee that my parents would be allowed to stay in Germany. Many people didn’t even know where Kosovo was; it wasn’t marked on most maps, as it was considered part of Serbia. Kosovo didn’t appear on their dark brown Yugoslav passports either — only the name of their city of origin was listed.

As a result, while my parents struggled for yet another piece of paper: a pink sticker labeled Aussetzung der Abschiebung (Duldung) — Suspension of deportation (tolerance), the tone at the immigration office grew increasingly harsh.

People with Duldung status were required to leave Germany as soon as the situation in their country of origin was deemed to have improved. That assessment, however, was made solely by the German government. My father received his first Duldung in February 1993; it was valid for just two months. Many more stickers followed, which differed only in the length of time they permitted: sometimes he was tolerated for five months, other times for just four. No one explained to him how this duration was determined.

My mother arrived in Germany a few weeks after my father. She also received a Duldung initially. The fact that her parents had lived in Germany since the 1970s had no impact on her or my father’s legal status.

From that point on, my parents did everything together — every visit to the authorities, every residence permit application.

Restriction after restriction

From the day we arrived in Germany, my parents were not welcome. That didn’t change with my birth in 1994. We lived from one temporary residence permit to the next, from one restriction to another, in what my parents describe as a kind of “prison.”

After months of living under Duldung status and countless trips to the immigration office, we received a status upgrade in 1995: a residence permit, Aufenthaltsbefugnis. It granted us more freedom; our movement was no longer confined to our city, and we were finally allowed to travel beyond it. A residence permit was still temporary, granted to foreigners under specific conditions, such as humanitarian emergencies.

I was officially granted permission to stay in my country of birth. But my legal status depended entirely on my mother’s. As a child of migrants, I didn’t have my own passport. Instead, I existed formally only in my mother’s travel documents, which is where my photo and personal details were recorded.

Today, as an adult, I look back at the note printed on my temporary residence permit when I was just two years old: Erwerbstätigkeit nicht gestattet — employment not permitted. To this day, I don’t understand why such a note was issued for a toddler. When I later asked the authorities for an explanation, they told me that, regardless of origin or age, the note was simply part of the administrative routine. That answer reinforced the feeling that we were not seen as individuals with names and identities, but only as numbers on pink stickers.

Three years after migrating to Germany, in 1996, my parents got married. But for their marriage to be officially recognized in Germany, they had to travel to the Yugoslav consulate in Hamburg, 200 kilometers from Braunschweig.

It was there that my last name changed — from Januzaj, my mother’s maiden name, to Ferizaj, my father’s surname. In the family, we still joke that my biological father adopted me.

On her wedding day, my mother had packed her camera to take a picture as a keepsake. But when they arrived at the consulate, they found themselves standing beneath a large portrait of Slobodan Milošević — the political leader of Yugoslavia and Serbia, and the man responsible for the repression and persecution that had driven her parents to flee their country. Quietly, she left the camera in her bag. Her wedding, like so many moments in her life in Germany, became just another administrative procedure.

In 1998, two years after my parents were married, the man in the photo at the consulate was also responsible for the war that broke out in Kosovo, which saw over 13,000 people killed and more than one million forcibly displaced internally and externally from the country. During the war, we were considered “lucky.” The officer in charge had now known us for five years, and for a while, our regular visits to the immigration office had paused. We had even received a sticker in our Yugoslav passports that protected us from deportation until June 1999.

I was told I should be grateful — grateful that I was safe because I wasn’t in Kosovo. But ever since that moment, I’ve carried guilt for being safe while my peers in Kosovo were not. I also felt a strange sense of gratitude toward the official handling our case, even though my parents had to fight their own battles at the immigration office, not just to keep us safe from war, but to shelter those who had fled Kosovo and found refuge with us.

This included my grandfather, Adem, and my grandmother, Ajmoni — my father’s parents. For Adem, it wasn’t the first time; he had lived in Germany in the 1970s. For my family, it felt like a duty to help as many refugees as possible — and the fact that our own status in Germany was uncertain and often at risk did not diminish that sense of responsibility.

Many of my relatives who came to Germany began working as translators, helping refugees from Kosovo understand their situation, obligations, and rights, so that, at least in administrative terms, their arrival would be easier than that of my parents.

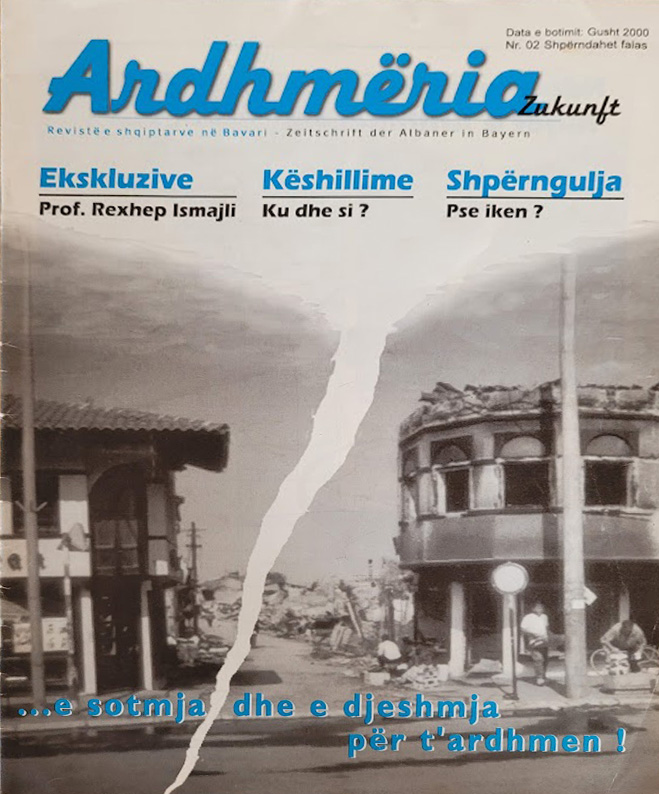

Meanwhile, 600 kilometers south of Braunschweig, my uncle, a computer science student, was organizing demonstrations in Marienplatz, the central square in Munich, one of Germany’s largest cities, to raise awareness about the situation in Kosovo. Like many others, he had left Kosovo in 1991, during a time when Albanian boys and men who had been conscripted into the Yugoslav army were returning in coffins, with official claims that they had committed suicide.

He also published a magazine for self-organized Albanian students called Ardhmëria (The Future), in both German and Albanian. Through it, he informed not only Albanian refugees but also German students about the war in Kosovo. The magazine also included guidance for navigating the immigration office — the Ausländerbehörde.

Both he and the Albanian friends who helped him publish the magazine and organize demonstrations were living on temporary residence permits at the time and faced the constant risk of deportation themselves.

The family members who were staying with us as refugees at the time also faced similar threats. My uncle, then just 14 years old, had organized an escape from Strellc to Albania, and from there, via Italy, to Germany. Because he had watched many German television programs and had brothers already living in Germany, he had taught himself the language while still in Kosovo. As a result, he was able to answer the immigration authorities’ questions upon arrival without any difficulty.

Ironically, as the family recalls, his fluency in German made the authorities suspicious. They questioned whether he and his paternal grandparents were “refugee enough” and even discussed the possibility of returning them to Kosovo — all while the NATO bombing campaign, which had begun on March 24, 1999, was still underway. My grandfather Adem did, in fact, know German — he had worked in Germany during the 1970s.

The assurance that we would not be deported from Germany ended in June 1999, when Kosovo was liberated. From that day on, the process of applying for residence permits resumed — and with it, the threat of deportation returned. Some of my family members who had taken refuge with us were allowed to stay, while many others were deported — including my grandmother, Ajmon, and my grandfather, Adem. My cousin, the son of my aunt, was also deported. He had been born in Braunschweig, just 25 days before me. Everything changed suddenly. He was deported from the city where he was born. I lost my childhood friend.

Families were also separated. For example, my uncle was separated from his wife and daughters, who, like me, were born in Braunschweig. After the war, he was allowed to remain in Germany, but his wife and daughters were not. My mother still remembers the day they were deported from Hanover Airport in 2000.

The security checkpoint and the waiting area were separated by a glass wall. My cousin, then two years old, looked at her father — my uncle — through the glass. It was only at that moment that she realized he wasn’t coming with them. She knocked on the window and met his eyes, just before continuing on to the next section.

A year and a half later, in 2001, my uncle managed to return to Kosovo. He was seeing post-war Kosovo for the first time — and was realising that he had become a stranger to his youngest daughter. Eventually, he succeeded in bringing them back to Braunschweig, where the cousins finally began to learn the language of the country where they were born: German.

Meanwhile, my parents decided to stay in Germany — contrary to what had been their original plan, to return as soon as things improved in Kosovo. On one hand, they wanted to continue supporting their families in Kosovo, as they had during the war, while on the other, they wanted to ensure that my brother and I could have a better life.

And so, we began going to the immigration office once again.

What connected us wasn’t the language of words, but the language of play and endless waiting.

I had grown up a little by then, and I remember those yellow corridors. What stuck with me most was the long waiting times and the smell of the green plastic chairs. It was hot in the summer, and I didn’t understand why we were sitting in a corridor wafting with the scent of plastic instead of going to a swimming pool.

I also remember playing with other children who, like me, had roots somewhere beyond Germany. What connected us wasn’t spoken language, but the shared language of play — and of waiting, which seemed to go on forever.

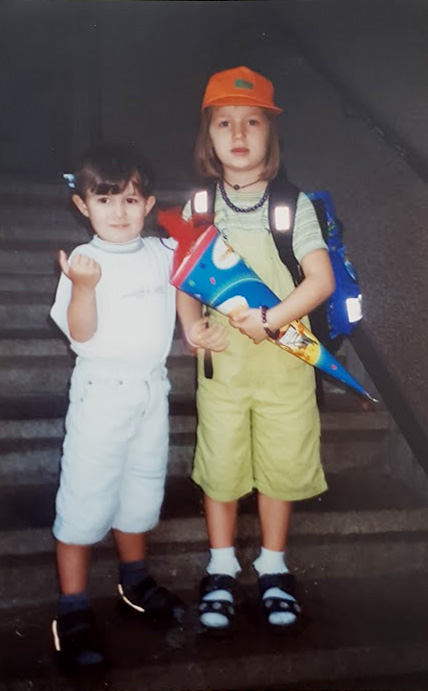

I also clearly remember my first trip to Kosovo after the war, at the end of 2001. There weren’t many flights to Prishtina at the time. This trip was especially meaningful for my parents — they were returning to a free Kosovo, and it was the first time our whole family traveled by plane.

When we finally arrived, the traces of war were everywhere. The burned-out houses stood in stark contrast to life in Germany — a contrast I only fully understood later. Back in Germany, I didn’t talk about the signs of war. Instead, I told my classmates about rural life with my grandparents in the village. After all, playing with the chickens that ran freely through the yard was something the other kids didn’t have. Only the teachers would ask about the war, which I would find frustrating because my time in the village no longer seemed interesting against something so mournful.

My school days

In 2000, I enrolled in school. This made no difference in our residency status. We hoped that the integration we were expected to achieve would bring change, but we continued receiving one temporary residence permit after another.

In one respect, there was an expectation to integrate perfectly: I attended a German school and earned top grades in German class. I outperformed my classmates in dictation, even though I only spoke Albanian at home. I was also the best in the class in German history.

But I was also, due to my residence status, placed in Deutsch Förderunterricht — remedial German language courses. Only students with deficiencies in German were placed in those classes. I was deeply upset that it wasn’t my knowledge, but the pink sticker in my passport that determined my path at school.

Every summer, we went to Kosovo. I was no longer bothered by the surprised looks from other children in the class who talked about their plans to travel to Italy, France, or the United States, and kept asking, “Don’t you want to see some other place in the world?” or “There are much more beautiful places in the world, why do you spend your vacation somewhere so boring?”

It was clear that we wouldn’t be going anywhere else for vacation. I was the only Albanian in the class, and I had gotten used to being the foreigner. Trips to Kosovo were trips home — a kind of escape from my classmates’ words. These trips became almost the only way to see our family there. For decades, Kosovar citizens faced a strict visa regime to travel to the Schengen area, including Germany, where we lived. Family members in Kosovo had to overcome a mountain of obstacles and expenses just to obtain a visa to join us — and even then, nothing was guaranteed.

It was the one trip where my parents truly seemed happy.

I looked forward to the final days before departure, even though my parents were stressed about forgetting something, and despite the exhausting journey. Immediately after the war, like many other Albanians, we avoided traveling through Serbia and instead drove for three days straight through Germany to Bari in southern Italy, then took a ferry either to Tivat in Montenegro or Durrës in Albania, and from there finally to Kosovo.

But even holidays in Kosovo weren’t free from bureaucracy. We needed a new passport and had to go to Deçan to get it. I remember clearly the building, surrounded by white cars with black UN lettering parked around it.

In 2003, we applied for passports issued by the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK), under whose protectorate Kosovo had been placed immediately after the war.

We waited there to be called, just as we had at the immigration office in Germany. The waiting room was packed with Albanians from the diaspora, like my parents and me. It was hot and cramped, the windows fogged up from the heat, made worse by the crowd. I hated this endless waiting — this dependence on an authority figure.

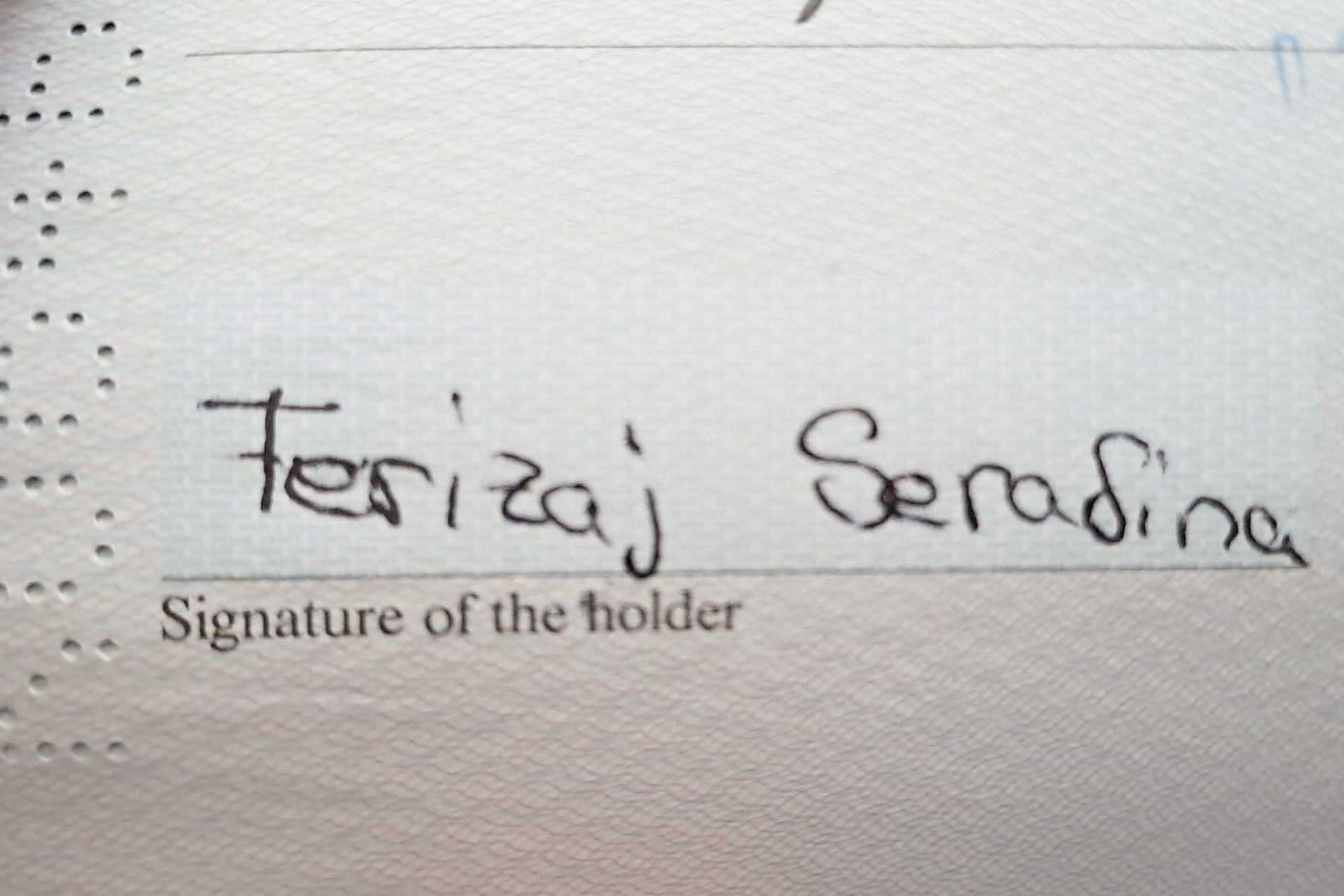

When our turn finally came, things moved quickly. There were Albanian workers, non-Albanian UNMIK staff, and a translator. Photos were taken. In mine, you can see the fatigue from the long day. The UNMIK passport was finally printed, and I was allowed to sign a document for the first time in my life, so I wanted to do it properly, without any mistakes.

When I wrote “Ferizaj, Serafina,” the Albanian translator scolded me: “You made a mistake. Here in Kosovo, we write the first name first, then the last name. You’re not in Germany.” I felt ashamed, and at that moment I realized, for the first time, that people in Kosovo didn’t see me as Albanian, but as German. Meanwhile, in Germany, I was Albanian. What was I now, and what did I have to do to be accepted?

Still, I was no longer listed in my mother’s passport. I now had my own, even if it wasn’t from Germany, where I was born. I didn’t yet realize that my travel options were extremely limited. For me, the only thing that mattered was being able to travel to Kosovo.

Forever avoiding deportation

The holidays in Kosovo ended with the start of the new school year. In 2004, I began attending a German high school. The temporary residence permits continued. The fact that I had made it to high school made no difference. From then on, I became the one translating letters from German authorities for my family. Even though I had once been placed in Deutsch Förderunterricht, I had already mastered the vocabulary of countless government offices.

During this time, my uncle came to Braunschweig from Munich. I didn’t understand why he had left the city, especially since he always said he loved Munich and enjoyed living there. But I was glad he was with us, especially because, as a graduate of the Technical University of Munich, an elite institution, he could help me with my math homework.

It was only a few years later, when he returned to Munich, that he explained the reason: he had wanted to avoid deportation. He told me how he had been forced to sign a document pledging to leave Bavaria as soon as he received his university degree.

His native language was Albanian, but because Kosovo was part of Yugoslavia, the authorities considered him “Yugoslav,” even though there was no such thing as a Yugoslav language.

He managed to avoid deportation, and a year later, he obtained German citizenship. I remember that day well. He came to visit us, and we each took turns looking at his German passport — not because it was some kind of prized treasure, but because it was a necessity, a lifeline. That day, I uttered the sentence that would follow me and many others through our identity crises: You are German.

Years later, he told me how difficult the process had been and how hard he had fought for his dignity. To obtain German citizenship, he had to renounce all previous citizenships. He had once held a Yugoslav passport, but he didn’t want to keep it — he wanted a document from Kosovo. The problem was that the UNMIK passport didn’t include any information about citizenship. It only stated that the passport holder was a resident of Kosovo, which complicated everything.

For this reason, the authorities asked my uncle to prove that he was of Albanian origin, without specifying what kind of proof was required. Many, including my parents, used certificates from schools where Albanian language and literature were taught. However, in my uncle’s generation, this was often referred to simply as “mother tongue” rather than explicitly as “Albanian.” His native language was Albanian, but because Kosovo was part of Yugoslavia, the authorities labeled it “Yugoslav,” even though no such language existed.

My uncle ultimately managed to prove his origin using an old document from the time he worked as an Albanian-German-Albanian translator for refugees during the Kosovo War in 1998–99.

Residence laws and their implementation still vary across Germany’s 16 federal states. In conversations, people often share different stories about how they obtained citizenship — each one unique from the next.

After receiving German citizenship, my uncle returned to Munich not long after. Once again, I felt that people would leave me simply because of a piece of paper. A piece of paper that determined where we could and couldn’t stay.

On January 31, 2006, the time had come: we went to the immigration office after my parents and uncle had spent many nights writing their CVs and explaining why they wanted to obtain German citizenship. They had carefully collected all the required documents. Every stage of the CV had to be supported with corresponding documentation.

I also remember the pain when my relatives, who were also fighting for German citizenship at the time, told me: “You are German now.” But I didn’t feel that way.

It still feels strange to me, even today. To obtain German citizenship, you had to deregister your UNMIK passport — in other words, give up all other citizenships. At the same time, the authorities didn’t believe we were of Albanian origin. Yet when we asked them what we were, they simply said, “We don’t know — you should know better than us.”

Without saying a word, I signed the papers handed to me with “Serafina Ferizaj,” just as the woman in Deçan had instructed me. Finally, the woman at the immigration office asked the question that still haunts me — the one that triggered my identity crisis: Deutschland oder Kosovo? Germany or Kosovo?

I know that some have also been asked: Deutschland oder Serbien? Even until a few months ago, people with a passport from Kosovo, in order to gain access to German citizenship, were required to deregister in Serbia. This was because they were registered not as citizens of Kosovo, but as citizens of Serbia, and as a result, they had to give up a citizenship they never held: Serbian citizenship. Some applied for Serbian passports only to surrender them immediately. Others were unable to obtain German citizenship at all because of this rule. We, too, were once registered as Serbian citizens.

In a low voice, I answered “Deutschland” — Germany. I didn’t want to give that answer. It felt like I was betraying my parents’ homeland. At the same time, I knew what my parents had fought for, year after year. I also remember the pain when my relatives, who were themselves struggling to gain German citizenship, told me: “You are German now.” But I didn’t feel that way.

To be and not to be German

That’s how I began researching my family history. I learned a lot about my parents’ lives as foreigners in Germany, through the official documents I had translated without fully understanding. I came to understand the choices we had to make, the bureaucratic hurdles, the constant uncertainty and tension, and the confusion all of this created.

While my UNMIK passport stated that I was a resident of a country I only knew from summer vacations and family stories, the documents from my country of birth defined how far I could travel and how long I could stay. Tolerance upon tolerance, and countless residence permits later, I finally obtained German citizenship in 2006.

Although many things became easier after gaining citizenship, the feeling of belonging neither here nor there remained. But finally, after many years, in 2024, things began to take a different turn.

In January 2024, visa liberalization was introduced for citizens of Kosovo. My uncle’s son was able to visit me in Munich, where I showed him the famous Bavarian beer and Marienplatz, the square where my uncle had organized demonstrations 25 years earlier. At last, the door to the world was open for them too.

In March 2024, I also remember when, on a return flight from Prishtina to Memmingen, a woman asked if I could accompany her. It was her first time visiting her children, who were spread out across Germany and Norway. It was also her first time at an airport. Now, she no longer had to wait for her children to visit her.

It felt natural for me to accompany her and help translate for her upon our arrival in Memmingen. When the German border police asked why she wanted to enter Germany, I thought of my parents and how they had been asked the same question when they first came to Germany in 1993: Warum sind Sie in Deutschland? — Why are you in Germany?

Then, in June 2024, the German government fulfilled its electoral promise: I was finally allowed to hold Kosovar citizenship alongside my German one. Shortly afterward, the Government of Kosovo announced that obtaining Kosovar citizenship would be free of charge for members of the diaspora. Almost a year later, in 2025, it was also decided that Kosovar citizens would no longer be registered as citizens of Serbia.

Things started to fall into place. I took my UNMIK passport, the one with the photo of my exhausted eyes, as it was required to prove that I belonged to Kosovo. With it, I returned to the same offices in Deçan that I had visited back in 2003. The offices had changed since then; everything was more modern, and the process was much faster than it had been 20 years ago. The only thing that hadn’t changed was the staff member.

Finally, at the age of 30, I found myself with both German and Kosovar citizenship. It felt like a cycle had finally come full circle. I felt freer. I was freer.

Feature image: Collage of photographs from the author’s archive.

Want to support our journalism?

At Kosovo 2.0, we strive to be a pillar of independent, high-quality journalism in an era where it’s increasingly challenging to maintain such standards and fearlessly pursue truth and accountability. To ensure our continued independence, we are introducing HIVE, our new membership model that offers an opportunity for anyone who values our journalism to contribute and become part of our mission.

Become a member of HIVE or consider making a donation.