Sitnica: The poison that flows

Tracing the pollution trail along the Sitnica.

By Uran Haxha — 8/7/2025

The gurgle of the Sitnica is barely audible as it winds its way through a riverbed filled with garbage. Along its 90-kilometer journey through Kosovo, the river passes cities, villages, roads, and industrial zones — each of these, in their own way, leaves their mark by degrading the river. The foul odor extends to nearby cities as the river winds through its course.

On the banks of the Sitnica River, living creatures and vegetation have become increasingly rare. The once clear water has become murky, and where fish once swam, garbage now floats. Among a half-ruined bridge, lay a dead crow, detergent packages, and sewage residue. “A good day is signaled by its morning,” the saying goes, and from this bridge, where one of the Sitnica’s forming branches, the Sazli River begins, the image of a deformed river emerges.

The odor coming from the river spoils the peaceful and picturesque view of the village of Sazli in Ferizaj, where vehicles delivering products to local shops and plowing tractors are some of the only noises heard during the day.

The heavy smell from the river accompanies the students who attend classes every day at the school of the village, “Arsim Rexhepi,” located about 100 meters away.

In the village of Sazli, the houses of the Bislimi family, like others in the village, are lined up one after the other. The most affected by the river’s stench is Muhamet Bislimi, whose house is very close to the Sazli River. To avoid flooding from the river, which often overflows its banks, he has added a thick layer of gravel to lift his orchards, which he has planted with apple and plum trees.

“This river is small, but it can cause a lot of damage,” says Bislimi as he takes out a cigarette and lights it. “You see, I’ve raised the ground up high, but still, it can cause trouble.”

Years ago, Bislimi moved to Sazli from Biti in the Sharr Mountains, one of the cleanest areas in the country. He says he always regrets building his new house in Sazli.

“I came here from there [Biti] 13 years ago because it was too far for my children to go to college,” says Bislimi. “We came here with our whole family and settled down. But to be honest, I regret it, because my children have all gone abroad.” Bislimi works as a forest ranger and tries not to spend time in Sazli whenever he gets the chance.

“From the middle of May until winter sets in, I go to Biti. We cannot stay here. We can’t even go out in the yard or anything. Even when the children come, they don’t want to stay here,” he says, mentioning that he has heard there are plans to start building sewage pipes, but this seems like a distant reality.

The Sitnica River is the most polluted in the country, as per every report by the Kosovo Environmental Protection Agency (KEPA), an independent institution within the Government of Kosovo.

Besime Kajtazi, a water engineer who developed her doctoral thesis on the Sitnica River, explains that this river carries all the urban waters of large settlements such as Prishtina, Lipjan, Fushë Kosova, Obiliq, and Graçanica, without any treatment.

Throughout its entire course, the Sitnica River functions as an open channel that collects wastewater, none of which is connected to treatment plants. In Lipjan, the river’s current increases along with the pollution because a stream from Shtime joins it. Near a promenade full of restaurants, wastewater flows directly into the river just like it does in the rest of the city.

According to the 2023 report of the Water Services Regulatory Authority (WSRA), only 8.1% of the country’s population is connected to wastewater treatment plants.

This number has increased significantly since 2021, when Kajtazi was studying the waters of the Sitnica. At that time, only 3.5% of the population was connected to wastewater treatment plants. According to her, the extent of these plants remains low, mainly due to high costs.

“[The plants] have high construction costs, but operation and maintenance are also costly, which would result in higher water and sewage service tariffs for citizens,” she says. In April 2025, however, good news came from the Ministry of Economy (MOE): Vushtrri and Mitrovica will finally have a wastewater treatment plant, which will be built with support from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD).

The inclusion of Mitrovica and Vushtrri in the wastewater treatment system will significantly increase the percentage of citizens connected to treatment plants. Meanwhile, however, many of Kosovo’s major cities, such as Prishtina, Gjilan, and Ferizaj, will still lack such facilities. Even the existing plants do not have sufficient capacity. For example, the regional water supply company “Hidrodrini” in Peja, which is considered to have the best performance, treats only 23% of wastewater.

At the entrance to Vushtrri, the Sitnica River flows past two large embankments, which were built as flood protection measures. Agim Kutllovci, 61, clearly remembers the volunteer workers who built them.

“I was born and raised here at the base of the Sitnica River,” says Kutllovci. “I remember very well how we used to swim, what kinds of fish there were, and how the entire riverbed was filled with willows, forming a sort of tunnel.” He recalls a distant time when people used the banks of the Sitnica River as if they were beaches.

But now, the heavy odor from the river, which becomes unbearable with the arrival of the warmer seasons, reaches Kutllovci’s house.

“When the sun rises, we have to lock ourselves in our houses, because of the stench,” he says, pointing to his home. “It smells like a catastrophe. In addition to the stench, all the mosquitoes come into the house, and you can’t even stay comfortably in your garden. I went and bought poison and sprayed the whole house.”

He occasionally shifts the conversation back to the 1970s and early 1980s, recalling a time when the river teemed with large, healthy fish weighing up to one kilogram. This story, however, takes a different turn in the early 1980s, with the arrival of the thermal power plants. The commissioning of the “Kosova B” thermal power plant, which had one unit in 1983 and a second in 1984, started to pollute the Sitnica River. A 2003 report notes 1983 as the date when the Sitnica was first contaminated with phenols — harmful chemicals originating from factories and industrial waste, which, even in small quantities, can poison water. They often give the water an unpleasant odor and a plastic-like taste, making it dangerous to use.

Since phenols are classified as heavy pollutants, their impact is hazardous. When they enter rivers, they pose a serious threat because their toxicity harms aquatic organisms, disrupts the balance of ecosystems, and can endanger human health, especially if water used for drinking becomes contaminated. Phenols occur naturally in plants but can be produced synthetically for industrial and medical purposes.

These pollutants should be stored and treated, as they are stored and treated at present by the Kosovo Energy Corporation (KEC). Nonetheless, in the past, leaks have occurred. Several scientific papers have documented such leaks, including a 1991 paper by Serbian scientists in the British scientific journal IWA Publishing, which identified phenols in the Sitnica River from the nearby power plant. In 2002, chemists from the Faculty of Natural Sciences at the University of Prishtina (UP) also found phenols in the water of Sitnica. In 2003, phenols became a bone of contention between Serbia and the United Nations administrative authority in Kosovo (UNMIK), after the latter was fined for leaking phenols into the Sitnica River that flows into the Ibar River in Serbia, causing drinking water contamination in the city of Kraljevo. The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) prepared a special report confirming this event.

Evidence of phenol can be found in the Graçanka River, which flows into the Sitnica and passes through the Kishnica mine, where more heavy metals and phenol are found.

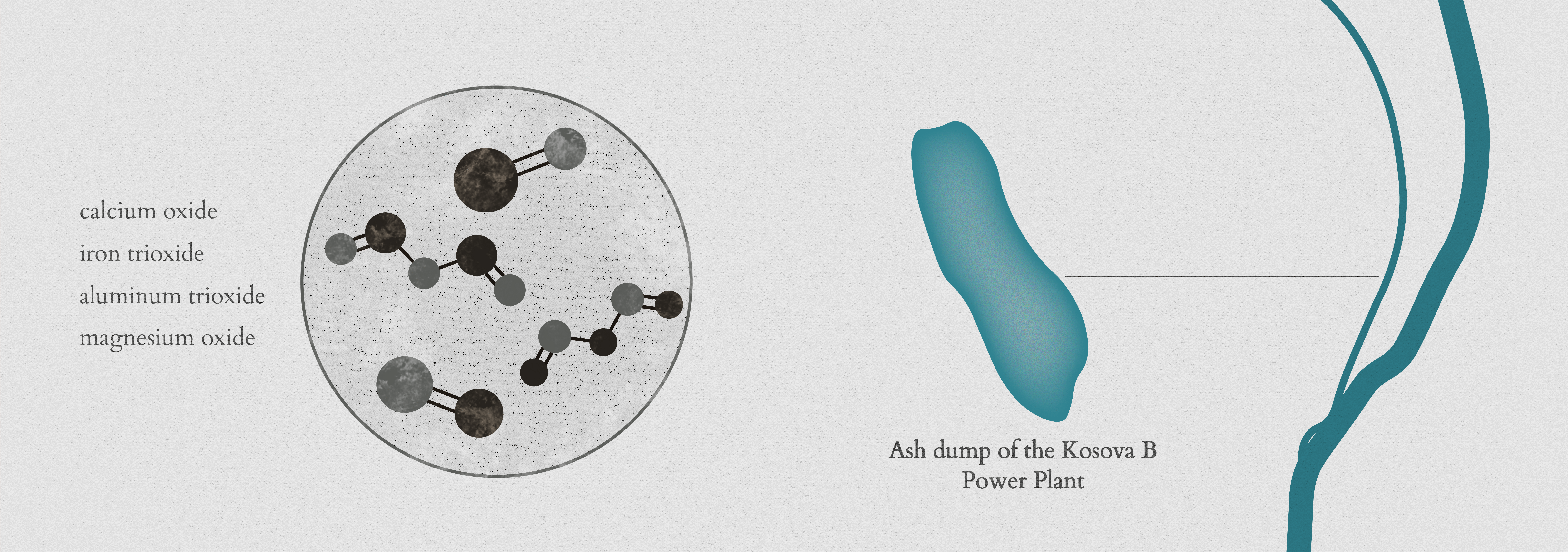

Thermal power plants in Kosovo, although frequently targeted as major polluters, are rarely mentioned for their polluting impact on rivers. Along its path, the Sitnica River flows beside ash dumps and even crosses the “Kosova B” thermal power plant facilities. A field visit is easiest in the village of Kryshevc in Fushë Kosovë, located near the border with Obiliq.

There, the river flows near an ash dump and a “blue lake,” formed by waters from coal combustion ash residue, which are deposited through the hydraulic system from the “Kosova A” and “Kosova B” thermal power plants. These waters also contain hazardous chemicals.

When these chemicals mix with water, the water takes on a completely different appearance, comparable to bleach.

This lake is located within a 50-meter radius of the Sitnica River. Another water discharge channel, which flows from KEC, is connected to this lake. It has three pipes that release polluted water directly into the Sitnica River. From the discharge point, a change in the color of the water is noticeable.

This discharge into the Sitnica River is not documented in the KEC environmental impact report for 2023. Instead, the report locates another discharge point on the other side of the power plant, near the village of Caravadica. According to the report, 621,545 cubic meters of water were released into the Sitnica River in 2023. The quality of this water is not mentioned in the document.

According to Kajtazi, the report is not accurate due to the poor placement of the water quality monitoring point. She explains that the sampling site, where water samples are collected for monitoring, is located five kilometers downstream from the discharge point. As a result, these findings are not a true reflection of the quality of the river’s water because, over that distance, the polluted water is diluted and undergoes self-purification through the natural processes of sedimentation and oxygenation.

From here, the Sitnica River runs through the inner area of KEC, where it is crossed by a conveyor belt transporting coal for combustion. According to the analyses that Kajtazi has cross-examined, the Sitnica River is essentially a river of poison, destroying all forms of life within it. Its aquatic ecosystem is practically in collapse. Data from the 2022 Environmental Report by KEPA raises the same alarm. Everything that flows from the Sitnica is outside normal measures.

All monitored points show high levels of pollution, with alarming violations of water quality standards. The Prishtevka and Graçanka rivers, as tributaries of the Sitnica, play a key role in raising pollution levels, bringing extremely polluted waters into the river’s stream.

At the entrance of Mitrovica, the Sitnica River flows past the former shock absorber factory, which is now out of operation. According to Ali Uka, who grew up on the banks of the Sitnica, the heavy odor carried by the river once made life there impossible.

“I have been living here for 48 years, and I remember the Sitnica very well. When the shock absorber factory was operating, it was a disaster. The smell was very, very bad. Now, compared to then, it’s better,” says Uka, who does not hesitate to confront citizens throwing rubbish into the riverbed of the “2 Korriku” neighborhood. “I’ve installed several cameras from my house pointing directly at the river, and I keep the camera lights on. This stops people from throwing away their garbage; otherwise, no one cares,” he says.

Both sides of the riverbed are filled with rubbish. From time to time, along the river, you can find the remains of dead animals or the corpses of animals slaughtered by butchers, all discarded as if the river were simply a dumping ground for excess waste.

Uka says that, despite having reported this practice to the police and local authorities, nothing has changed.

Air pollution

Environmental pollution is not the only problem worrying the residents around the Sitnica. They also face another unavoidable issue: the heavy stench that contributes to air pollution. During the summer months, when evenings and mornings are cooler and water temperatures rise, unpleasant odors spread everywhere.

River pollution can affect air quality through various processes, especially the decomposition of organic matter and the release of chemicals and gases from the water into the atmosphere. Water pollution, particularly from industrial chemicals such as mercury, arsenic, and volatile organic compounds, mixes with water vapor and pollutes the air.

“Mines and areas around polluted rivers often contain sediments loaded with heavy metals and toxic substances. In drier periods or when the water recedes, these sediments dry out and turn into dust, which spreads into the air. This process pollutes the air with elements like lead, cadmium, and chromium,” says Shala.

The window of time is closing

Like a poisonous snake, the Sitnica winds through Kosovo, while solutions to its pollution seem out of reach. Nature often has self-defense mechanisms; the self-purification of water is one such example, a natural process that might have defended this river at some stage. But, according to Shala, the damage caused to the Sitnica is so great that it has lost all its natural defense mechanisms. The river can no longer save itself.

Despite the scale of the ecological crisis that has gripped the Sitnica River, experts do not see it as a lost cause. On the contrary, they claim recovery is still technically possible, but it requires concrete measures, prioritization by central institutions, budget allocation, and public involvement.

According to Kajtazi, the construction of plants for the treatment of urban and industrial wastewater is the most urgent and fundamental measure for any sustainable recovery. In addition to budget allocation and community involvement, industries that pollute the waters must also pay.

Agron Shala, a water quality monitoring expert with over two decades of experience, emphasizes that the crucial first step is a simple one: identify pollutants. “We should create a cadastre of surface water pollutants as soon as possible. If we don’t know exactly who is polluting and what is being discharged, any [recovery] plan remains incomplete,” says Shala, noting that currently no such database exists.

For Shala, treatment plants are only part of the solution. He also advocates for financial support to be given to the private sector so that treatment systems can be installed for small to medium-sized industries. He emphasizes the importance of building professional human capacities at all levels of public administration related to water quality control and management.

“The possibility for real improvement exists,” says Shala, but he emphasizes that there is a lack of political will and that no government has so far addressed the water issue.

The seriousness of the entire situation is evident in the limited resources allocated to the KHI. “Since I started working at the Hydrometeorological Institute, we have never had more than three people employed in the water quality monitoring sector. Three people to cover the entire country,” says Shala.

He calls this “absurd,” especially in light of there having never been an official position for biological water monitoring, meaning that no expert has been dedicated to analyzing the impact of pollution on aquatic life and biodiversity. Anything related to such monitoring has been the result of support from the EU or Swiss organizations, with not a single step taken by local institutions.

For years, even when KHI employees retired, they were not replaced. Only recently was a vacancy announced for two new positions, which will focus on physical and chemical monitoring, but not on the biological aspect of pollution. “Is this number sufficient? I have no comment,” he says.

Both experts are convinced that the Sitnica can be saved, but the window of time is closing. “Every year that passes without action makes recovery more difficult and more costly,” says Kajtazi.

Feature Image: Ferdi Limani / K2.0

Photos: Ferdi Limani & Uran Haxha / K2.0

Ilustrations: Dina Hajrullahu

This blog was published with the financial support of the European Union as part of the project “Informed Democracy: Promoting a Diverse and Sustainable Media Ecosystem”. Its contents are the sole responsibility of Kosovo 2.0 and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.

Dëshironi të mbështetni gazetarinë tonë?

Në Kosovo 2.0, përpiqemi të jemi shtyllë e gazetarisë së pavarur e me cilësi të lartë, në një epokë ku është gjithnjë e më sfiduese t’i mbash këto standarde dhe ta ndjekësh të vërtetën dhe llogaridhënien pa u frikësuar. Për ta siguruar pavarësinë tonë të vazhdueshme, po prezantojmë HIVE, modelin tonë të ri të anëtarësimit, i cili u ofron atyre që e vlerësojnë gazetarinë tonë, mundësinë të kontribuojnë e bëhen pjesë e misionit tonë.

Anëtarësohuni në “HIVE” ose konsideroni një donacion.