Green Deal, we have a problem

Challenges to achieving full decarbonization by 2050.

By Uran Haxha — 27/11/2024

Whenever carbon emissions and other greenhouse gases from burning coal are discussed, Kosovo is criticized. As a small Balkan country still dependent on two thermal power plants, which should already have been decommissioned, Kosovo is at a key moment in shaping its energy future.

Kosovo’s energy security relies heavily on coal-fired power plants in Obiliq, just a few kilometers from Prishtina. The Kosova A power plant, built in the 1960s and the Kosova B power plant, constructed in the 1980s, generate electricity by burning coal.

Since the power plants’ inception, Kosovo’s abundant coal reserves have powered nearly every aspect of life. However, two of the five units at Kosova A, specifically A1 and A2, have long been out of service and now stand as huge iron relics, their motors and rotors no longer functioning.

Since the post-war period, successive governments have planned and discussed replacing power plants A and B with a new facility called Kosova e Re. After the 1998-1999 war, the World Bank supported a project for the new power plant, which was to be constructed by investors from Contour Global, a London-based energy production company.

In 2018, the government signed an agreement to build Kosova e Re, with construction expected to begin between 2021 and 2022. The proposed 500 megawatt (MW) power plant aimed to enable the complete closure of Kosova A and support investments in filters for Kosova B, which would operate during the transition until Kosovo develops sufficient renewable energy sources. Investors and the government, then led by the Alliance for the Future of Kosovo (AAK), claimed the new plant would feature advanced technology, setting it apart from the Kosovo Energy Corporation (KEK)’s existing facilities, the country’s sole public energy producer. They emphasized that it would produce minimal greenhouse gas emissions.

However, civil society in Kosovo strongly opposed this project, arguing that building a new coal-fired power plant would prolong the country’s reliance on carbon-based energy and increase electricity costs for residents to cover the investment.

In 2018, the World Bank withdrew its support for the agreement. After extensive debates for and against the project, investors from Contour Global also withdrew from the project in 2021 and sued Kosovo for failing to meet agreed-upon conditions. As a result, Kosovo lost the opportunity for a new power plant in the name of green energy, but remained dependent on two power plants that are among Europe’s largest per capita emitters of greenhouse gases.

Thermal power plants impact citizens’ health; they contribute to air pollution in Prishtina, Fushë Kosovë and Obiliq which often reaches dangerous levels. As the cold season arrives, the skies over Prishtina are filled with smog. In addition to the greenhouse gas emissions from thermal power plants, cars, which primarily run on oil and gasoline, contribute significantly to the pollution.

Power plants emit significantly more dust and greenhouse gases than the allowed limits.

Source: Bankwatch Report 2024.

Meanwhile, energy demand increases every year. Historically, winters in Kosovo have always been challenging in terms of energy demand due to the increased need for heating. Yet energy demand is also rising in the summer. Hotter summers and heat waves, driven by climate change, last for weeks and make air conditioners increasingly necessary for families and businesses. This puts pressure on the energy system, which cannot fully meet domestic consumption.

The lack of capital investment in energy has left Kosovo’s energy security fragile, preventing significant diversification of its energy sources. Domestic energy generation fails to meet demand and dependence on energy imports increases. In 2023 alone, import demand rose by 45% compared to 2022. Annually, energy consumption is covered more by imports than by renewable sources.

To meet the growing demand for electricity without relying solely on coal, Kosovo’s government aims to invest in renewable energy sources, improve energy efficiency in public buildings, as well as in the residential and commercial sectors and install filters in the existing thermal power plants.

Which sectors produce the most greenhouse gas emissions in Kosovo?

Source: Kosovo Agency for Environmental Protection

Kosovo’s government does not plan for any new coal-based energy generators and has committed to complete decarbonization by 2050. But the current pace of construction of new renewable energy generation facilities makes meeting this commitment a challenging prospect.

The fight against carbon emissions is one of the 21st century’s greatest global challenges. But despite their minimal carbon emissions, smaller countries often bear the greatest burden of climate change’s consequences. International organizations often impose similar decarbonization requirements on both major contributors to climate change and smaller countries like Kosovo. The financial assistance Kosovo receives to meet these new measures and global initiatives is also limited. With limited integration in international organizations such as the United Nations, which lead the fight for decarbonization, Kosovo faces financial constraints making it difficult to contribute to global decarbonization efforts.

Global goals and obligations, local capacities

Kosovo’s main challenge in achieving full decarbonization is transitioning from coal to renewables. As a developing economy, financial constraints limit its capacity to support large-scale renewable energy projects. Additionally, the need to maintain energy supply security and affordability during the transition to renewables further complicates the shift away from coal.

Despite these challenges, Kosovo has committed to international decarbonization efforts, taking on obligations crucial for its progress toward EU integration.

In 2020, Kosovo joined the Green Agenda for the Western Balkans, a strategic framework adopted by the EU to align the region with the EU’s European Green Deal. Western Balkan leaders formalized their commitment to implementing the Green Agenda by adopting the Sofia Declaration.

This agenda outlines specific conditions and obligations, which are then translated into goals for each member country. Through the Sofia Declaration, leaders pledged to significantly reduce carbon emissions, develop renewable energy and achieve sustainable economic growth.

These commitments present a significant challenge for Kosovo, as coal powers all industries, the Energy Community told K2.0. The Energy Community is an international organization that unites the EU and countries seeking EU integration to create an integrated pan-European energy market. It was brought into existence by the Treaty Establishing the Energy Community, which was signed in October 2005 in Athens, Greece, and entering into force in July 2006. Its main objective is extending the EU’s internal energy market rules and principles to southeastern Europe, the Black Sea region and beyond, based on a legally binding framework.

By signing this treaty, Kosovo has made commitments it must fulfill. In 2022, the Energy Community’s Ministerial Council set goals for 2030, which include reducing greenhouse gas emissions, increasing the share of renewable sources in final consumption and limiting primary energy consumption. For Kosovo’s energy sector, these goals mean that 32% of energy consumption must come from renewable energy sources by 2030.

How is electricity production covered and what are the goals?

These goals are outlined in Kosovo’s draft National Climate and Energy Plan (NCEP), a requirement from the Energy Community Council of Ministers. During consultations on the latest draft with Kosovo’s government, the EC requested that Kosovo finalize the Just Transition Roadmap. It emphasized that the country’s progress towards the 2030 climate objectives will largely depend on how the energy sector plans and implements sustainable changes.

In a conversation with K2.0, the Energy Community’s communications office stated that the current draft of the NCEP foresees coal-based energy dominating until 2040 and does not specify a date for the phasing out of coal. This contradicts the government’s commitment to full decarbonization by 2050.

“Furthermore, the lack of a Just Transition Roadmap has created uncertainty regarding Kosovo’s ability to transition equitably to cleaner energy sources,” the Energy Community told K2.0. A second draft of the NCEP was put for consultation at the end of November 2024 and is expected to be sent to the Energy Community Secretariat.

To meet the Energy Community’s 2030 goals, Kosovo must increase the share of renewable energy sources in its energy consumption from 12% to 32%. Kosovo’s government believes these goals are achievable through the implementation of documents like the Energy Strategy and the National Climate and Energy Plan, provided that the support is cross-sectoral.

Where does the electricity we consume come from and what are the goals?

However, according to Agron Demi, director of the Balkan Green Foundation, an organization that advocates for green energy in Kosovo, progress toward achieving these goals is not advancing at the necessary pace.

“Ambitious goals have been set on paper, but implementation remains slow as always, policies often change due to the lack of a sustainable and integrated approach,” said Demi. Though his organization and others are invited to participate in discussions to coordinate measures and actions for advancing this transition, their input is rarely considered.

Although Kosovo is not part of the EU, it is still impacted by measures implemented at the EU level for member states, such as the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). This mechanism imposes a cost on carbon emissions generated during the production of carbon-intensive goods.

One initiative by UN member states implements a carbon tax on domestic companies that emit carbon. The EU also imposes such measures, but many goods imported to EU states come from states without a carbon tax, like Kosovo. To address this, the EU plans to implement the CBAM, seeking to prevent carbon leakage — relocation of production to countries with less stringent climate policies — and encouraging cleaner industrial production in non-EU countries.

The EU plans to implement the CBAM in January 2026, for all countries that export to the EU. Sectors subject to this tariff will include producers of iron and steel, cement, chemical fertilizers, aluminum, electricity and hydrogen.

The CBAM will impact Kosovo’s exporters to the EU by increasing production costs and selling prices. Bujar Piraj from the Riinvest Institute explained that key export sectors, including metal industries and cement production, will need to adapt to stay competitive.

The rise in tariffs could also discourage foreign direct investment, given Kosovo’s heavy reliance on coal-generated electricity. “Kosovo will face additional challenges in attracting foreign direct investment,” said Piraj, stressing the importance of creating an environment that supports green technologies.

But Agim Mazreku, external advisor at the Ministry of Environment, Spatial Planning and Infrastructure, downplays the CBAM’s impact on Kosovo’s economy, mentioning the low number of exporting companies affected by the measure. “The impact on Kosovo’s industry from the CBAM will be less than 1% of the GDP,” he said.

Kosovo has yet to implement the important measure of establishing a carbon tax. The Kosovo Energy Strategy envisions creating a just transition fund using revenues from the carbon tax, but progress has been slow. The Energy Community recommends that this measure be implemented as soon as possible. “Implementing a carbon tax system would help reduce emissions and secure domestic resources for a just and sustainable transition,” it told K2.0.

In addition to fulfilling regional and EU-level obligations, Kosovo has voluntarily aligned its decarbonization efforts with the Paris Agreement, which seeks to limit global temperature increases to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. The implementation of this agreement serves as the foundation for the world’s largest climate change conference, the Conference of Parties (COP).

This year, COP29 took place in Baku, Azerbaijan, from November 11 to 22, 2024. It primarily focused on financing the fight against climate change. Member states can receive money from a fund of 100 billion euros to support their decarbonization efforts. However, Kosovo’s non-membership in the U.N. prevents it from accessing this fund.

United Nations Climate Change Conference COP29

COP29, held in Baku, focused on the financial agreements that developing countries will receive to facilitate their transition away from fossil fuels and adaptation to climate change. The conference agreed to triple financing for developing countries, increasing the previous target of $100 billion per year to $300 billion per year by 2035. It also secured a commitment from all stakeholders to work together to enhance financing for developing countries.

COP29 also concluded multi-year negotiations on carbon markets under Articles 6.2 and 6.4 of the Paris Agreement, establishing a strong framework for international carbon credit trading. These mechanisms will ensure environmental integrity and benefit least developed countries through capacity-building assistance and financial support.

However, COP29 has been marred by controversy, including the release of a recording showing the head of host country Azerbaijan’s team using the conference to negotiate gas and oil sales deals. The agreements reached have also been criticized as “insufficient and too late” by several countries in Africa.

The Paris Agreement was adopted in 2015 and establishes global carbon reduction goals. It requires each country to outline and communicate its climate actions after 2020 through a document known as the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC). Although Kosovo is not a signatory to the Paris Agreement, it has voluntarily drafted an NDC.

Mazreku presented Kosovo’s NDC, which pledges to reduce carbon emissions by 42% by 2030 compared to 2016 levels, at COP29. To achieve this goal, Kosovo needs 4.8 billion euros, of which it lacks 3 billion.

This means that Kosovo has five years to secure 3 billion euros. Since it is impossible to cover this amount with the state budget, which is projected to be 3.6 billion euros for 2025, Kosovo will turn to loans from the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), as well as financial assistance from the EU, Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) and other organizations.

Mazreku works directly with the government in combating climate change and managing the transition and sees the lack of necessary funding as the main problem. He explains that while Kosovo has strengthened the legal framework in recent years with the issuance of the Law on Climate Change, the law on the promotion of RES and the establishment of inter-ministerial councils to oversee the implementation of this framework, securing funding for implementation remains the primary obstacle.

“We are unable to receive or access most of the multilateral funds at the global level. This is problematic because these funds are grants, not loans from international institutions like the IMF or the World Bank,” said Mazreku.

If Kosovo could receive grants to finance climate change measures, it would not face financial obligations, as it would not need to repay the funds. However, in the case of loans, such as those from the World Bank or IMF, Kosovo would incur a financial burden over the long term, as it would need to repay the borrowed amount under certain conditions.

For example, the EU is one of the main institutions that funds initiatives in Kosovo through grants, but this has recently become more complicated. In June 2023, due to disagreements amid the Kosovo-Serbia dialogue, the EU imposed sanctions on Kosovo, halting funding for key projects.

With over a year of delays in these projects, the path to achieving the goals will take even longer.

Despite pressure from these adopted documents, progress on green energy initiatives has been slow. Investments in renewable infrastructure with larger capacities are not yet on the horizon and remain insufficient for making a significant difference compared to traditional energy sources.

Unlike in previous years, the 2023 report from the Energy Regulatory Office (ERO), an independent public agency that regulates the energy sector, said that there were no requests for licenses to produce energy over 5 MW from lignite, wind, water, solar, or biomass. Nonetheless, the ERO noted that there has been a consistent demand for information about these capacities, highlighting the real challenge of diversifying energy sources.

Diversification of energy sources, focused on renewables, largely depends on the natural resources and opportunities available on the ground. While solar and wind energy generation in Kosovo began only recently, hydropower has been the foundation of the country’s energy system.

Renewable energy sources’ slow path

Kosovo’s energy history began with clean energy sources. The first hydroelectric power plants were established in the 1930s, predating the construction of thermal power plants. At that time, the electricity demand of a population of around half a million was minimal. The economy primarily relied on agriculture and livestock, with little industrial development, except for the Trepça complex, a Balkan industrial hub specializing in the extraction and processing of lead, zinc and silver.

The primary resources available in the impoverished region were the rushing waters of the largest and fastest rivers. Hydropower plants in the Dukagjini Plain, including the Radavci, Burimi, Dikanci and Lumbardhi plants, formed the foundation for electricity generation in Kosovo. Together, these hydropower plants have an installed capacity of around 13 MW. Another significant plant built during that time is the one on Lake Ujman, which today accounts for half of all energy produced by hydropower in Kosovo. However, with Kosovo’s large coal reserves, the introduction of thermal power plants in the 1960s pushed hydropower out of the energy development plans.

Hydroelectric power plants only reappeared in government projects in 2009. This began with the Energy Strategy of the Republic of Kosovo 2009-2018, which included plans to invest in energy generation through water resources, supported by the government through feed-in tariffs. At the time, the Kosovo government’s policy aimed to encourage private sector investment in small hydropower plants by granting licenses for water use for energy production. State institutions issued licenses on a first-come, first-served basis. Ultimately, qualified investors benefited from a guaranteed sale price, and the country’s institutions, specifically the transmission system operator — KOSTT, in Kosovo’s case — purchased the energy produced.

At first glance, the initiative seemed promising. Pre-feasibility studies for water resources identified 77 potential locations for small hydropower plants in Kosovo. However, the construction of these plants quickly triggered alarm over the damage they caused to ecosystems and the lives of nearby communities. Private investors largely ignored these projects’ consequences on affected communities.

The construction of hydroelectric power plants, which began in 2012 in Kosovo’s streams and rivers, severely disrupted ecosystems. Intense construction work in the country’s mountains and plains showed little regard for nature. Angered by the destruction, residents chose protests as a form of resistance.

In the Štrpce area, resistance to these projects united Serbs and Albanians. The promise of “green” energy from hydroelectric power plants fell short, as the implementation was far from environmentally-friendly. This era ended with rivers damaged by the plants and the restoration required by environmental permits was never properly completed.

These hydropower plants’ limited power generation capacities were disproportionate to the damage they caused. Nonetheless, 18 remain operational. Together with the older hydropower plants, they contribute only 3% of Kosovo’s total energy, with the hydropower plant on Lake Ujman leading the output.

As investments in hydropower have stalled, the current government has shifted its focus to solar and wind energy.

With limited capacity to develop renewable energy generation, Kosovo’s government aims to attract investors through support schemes to help achieve its goals.

In the first half of 2024, Kosovo held its first solar energy auction. In such an auction, companies compete by bidding for the rights to construct energy generation facilities.

The auction was successfully completed, achieving 100 MW of installed capacity. The government secured the land for construction and guaranteed the energy’s purchase price. After several companies submitted applications, the auction — broadcast live and open to the public — concluded with a winning bid lower than the guaranteed price.

Construction, however, has yet to begin.

The government plans to hold an auction at the end of 2024 for 150 MW of wind power, to be developed in two phases. The project will involve a joint investment between the government and private entities. In previous years, wind energy investments led to two major projects: the SOWI wind park in Bajgora, Mitrovica, in 2019, and the Air Energy Kitka project in 2018. According to the ERO, the energy generated by the SOWI project will account for nearly half of all energy generated from renewable energy sources in 2023.

Investments in green transition

Kosovo recently signed an agreement with the European Investment Bank (EIB) to receive a 33 million euro loan and 29 million euros from KfW, a German state-owned development bank, for the construction of a 100 MW solar park, which is set to begin in 2025. This solar park will be built on land filled with ash from the Kosovo Energy Corporation (KEK). According to the EIB, the project will reduce CO2 emissions by approximately 174,000 tons annually.

Meanwhile, the construction of electricity battery storage capacities, as part of the Compact Program with the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), will become the largest project of its kind in the region. Signed in early 2024, this project will also establish a new enterprise, the Energy Storage Corporation, which will manage two 125MW batteries with a 2-hour duration (250MWh). KOSTT will own 45MW with a 2-hour duration (90MWh).

Meanwhile, the Energy Community emphasizes the need for additional regulatory steps, such as establishing clear auction guidelines and a three-year auction plan. It says that this would offer investors greater predictability and clarity on the future renewable energy landscape, create a stable framework for long-term investments and attract more private sector participation in the market.

Beyond the absence of a three-year auction plan, the government’s progress in opening auctions has been slow. If the wind auction procedures are completed by January 2025, it would only be the second auction the government has conducted in four years.

The promotion of renewable energy through prosumers — simultaneous producers and consumers such as businesses and citizens installing solar panels — is booming. However, obstacles arise from lengthy bureaucratic procedures that can take up to a month.

Both citizens and businesses must obtain a permit from the ERO to generate energy. Citizens must provide evidence of their annual energy consumption and production, an installation agreement with the system operator, and, if required by construction legislation, the municipality’s consent for the installation of self-consumption equipment. For businesses, the process involves 13 steps, which include submitting documents related to the company’s board, technical and financial feasibility studies for energy production over 1 MW and other required documents.

ERO’s register of applicants for self-generation as prosumers includes 718 authorized applicants. The government has supported citizens and businesses by exempting them from the construction permit requirement when installing up to 7 kW. But procedures are lengthier for investors wishing to install generators with larger capacities. The current pace will make it impossible to achieve decarbonization by 2050.

Arven Syla, an energy researcher pursuing a doctorate at the University of Geneva, emphasizes the urgent need for faster progress, as the power plants’ age threatens their sustainability.

“We cannot depend entirely on them. Any intervention in thermal power plants affects citizens because energy must be imported, which then impacts tariffs and directly affects citizens’ pockets,” he said. “Additionally, the lengthy procedures for building capacities, regardless of the type, should serve as an indicator to move faster.”

While projects to install new renewable energy source generation capacities have progressed slowly, the government, in cooperation with the EU and other donors, has recently aimed to prevent and reduce energy demand through the implementation of energy efficiency measures.

Energy efficiency

In general, buildings in Kosovo, both commercial and residential, lack proper insulation, which increases electricity demand, especially during the colder months. By reducing energy demand, Kosovo could lower operating costs for businesses and reduce household bills, making it easier to transition to alternative low-carbon energy sources without sacrificing economic growth.

The International Energy Agency (IEA), which represents OECD member states, says that improvements in energy efficiency could contribute over 40% of the reductions needed to meet the Paris Agreement’s objectives.

The energy crisis that gripped all of Europe following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine led the Kosovo government to launch its first support measures for citizens in early 2022, aiming to increase energy efficiency by subsidizing heating through efficient equipment. In the following years, the government also introduced several initiatives through open calls to help citizens and businesses acquire efficient equipment, as well as assistance in installing heating systems, replacing windows and insulating homes.

Before the winter of 2024, citizens could apply for support to insulate roofs and replace doors and windows through the Kosovo Energy Efficiency Fund (KEEF). They could receive subsidies of up to 5,500 euros, with a total fund of 5 million euros available. The call followed a first come, first served approach and closed less than a week after the fund was fully allocated. This highlights citizens’ growing interest in energy-efficient measures, driven by the potential for financial savings.

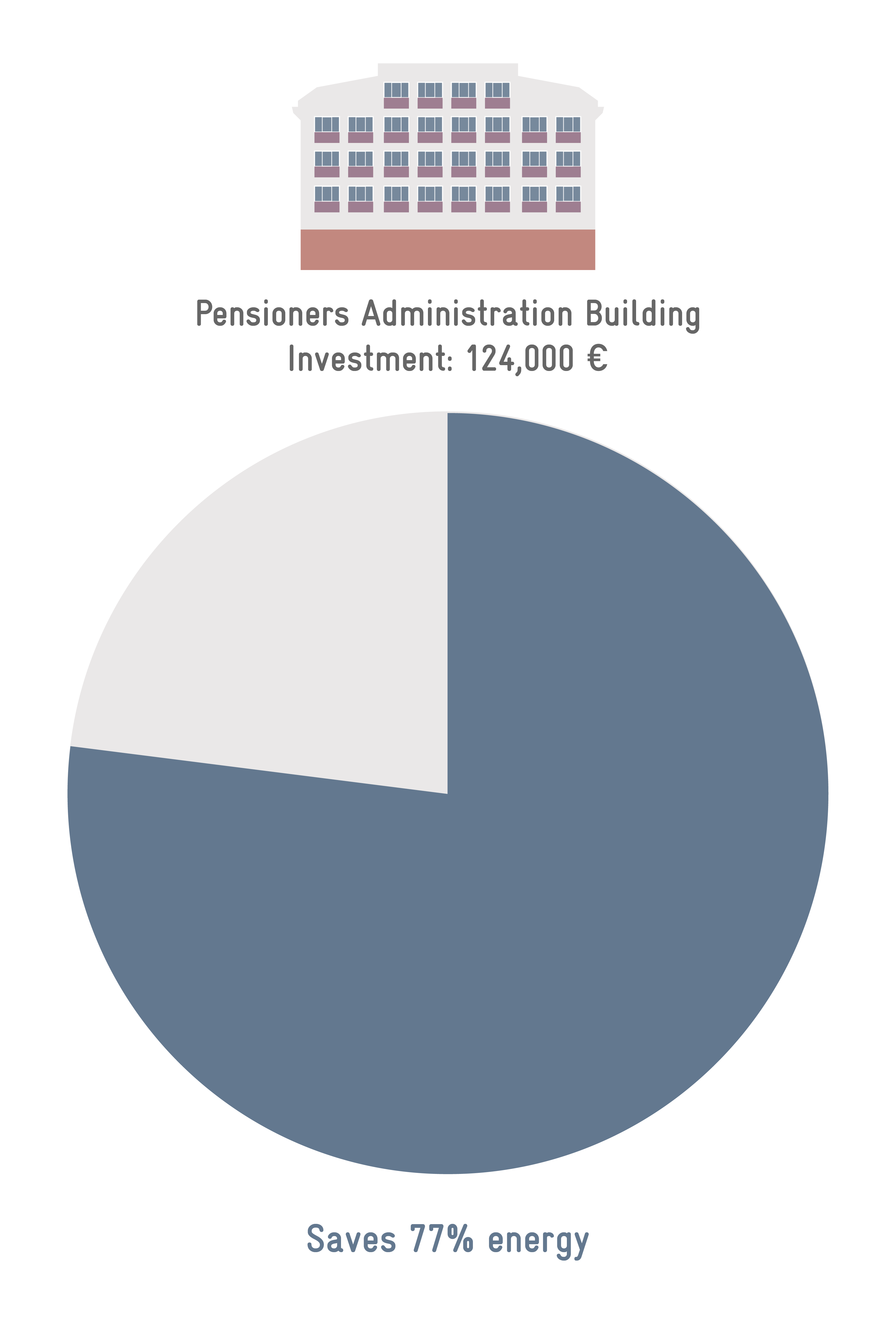

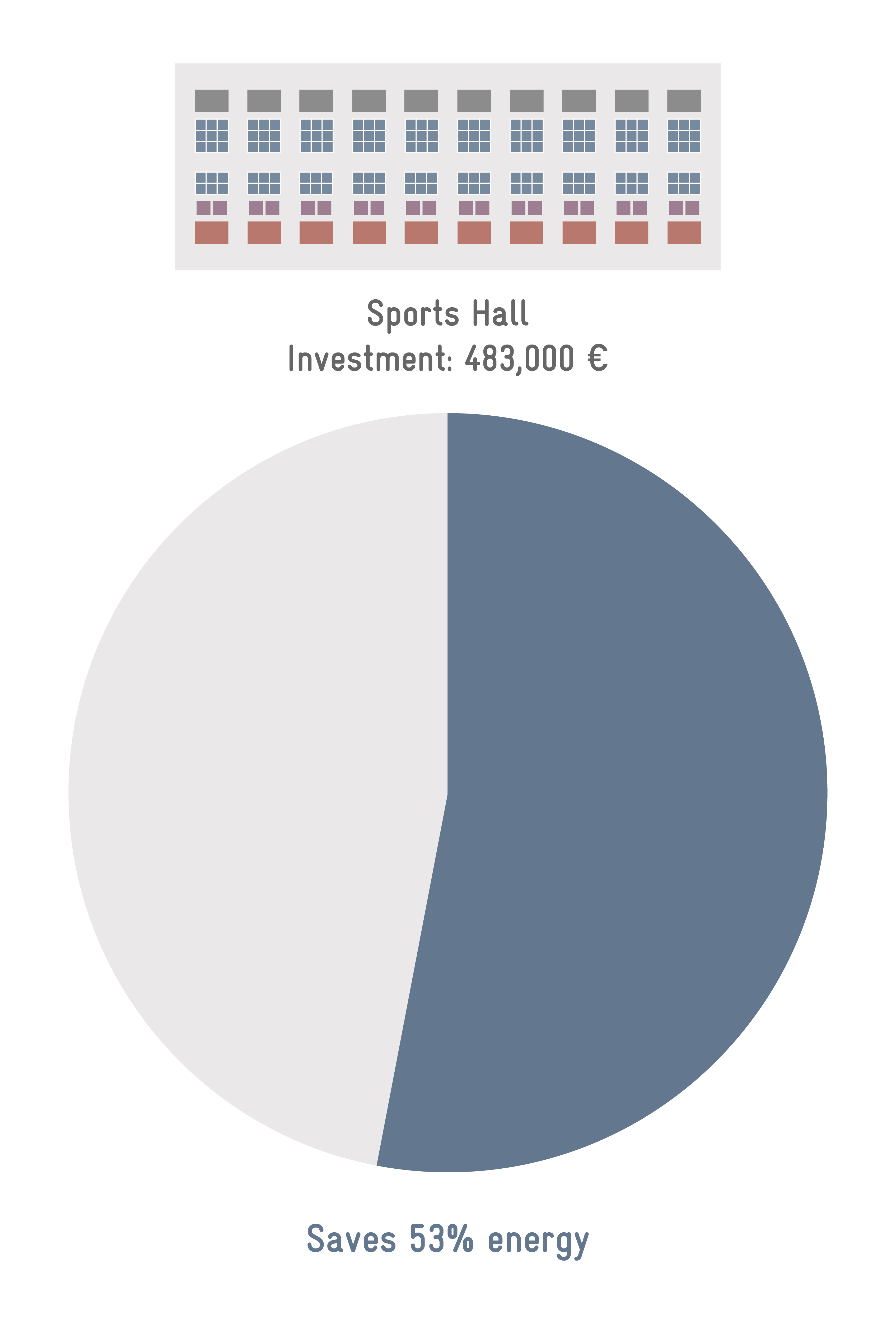

How much energy will be saved by implementing energy efficiency measures in various facilities in Ferizaj?

Source: Kosovo Energy Efficiency Fund

During 2023-2024, the Ministry of Economy also subsidized the purchase of heat pumps, energy-efficient air conditioners with high-efficiency inverter heat pumps, biomass boilers powered by wood, pellets, briquettes and individual biomass stoves. This led to high demand for purchases and contributed to an increase in energy consumption during the summer, due to the greater use of equipment that both heats and cools.

External donors such as the EU, MCC, and World Bank have supported all these measures through the KEEF, which was established in 2019.

In addition to support schemes for citizens and businesses, the KEEF and MCC have focused more on insulating and improving public buildings. Efficiency measures in public buildings, which consume more energy, aim to lower electricity consumption by reducing heating requirements. Simple changes like improving building insulation or adopting fuel-efficient technologies can significantly reduce carbon emissions without requiring costly new infrastructure.

Kosovo lacks a national building code that residential and commercial developers must follow. A building code would establish standardized criteria for each new construction to meet necessary energy efficiency requirements. In the absence of such a code, builders and investors/owners independently decide on which insulation to install in houses, buildings, or offices, regardless of building type. This contributed, by 2017, to the illegal construction of 300,000 buildings in Kosovo that failed to meet even the most basic building standards. As a result, energy loss in these buildings is high.

As efficiency measures are being implemented, the construction boom in Kosovo continues. While construction is now licensed, it still does not require adherence to a building code. Kosovo’s government now faces a crucial moment, as it aims to strategically develop a building code that would eliminate the need for efficiency investments in new construction, allowing these resources to focus entirely on improving older buildings.

The government has done little to help businesses transition to more efficient equipment or production lines. No initiatives have been introduced to encourage large enterprises to change their production methods.

The current government’s goals of decarbonizing power generation by 2050 and increasing power generation from renewable energy sources to 32% by 2030 are progressing slowly. The steps taken so far reveal a more complicated path to decarbonization. With limited funding, rising energy demand, excessive bureaucracy hindering investment and slow progress in achieving these goals, Kosovo may, at best, have cleaner air by 2050 but still rely on coal as the dominant source of energy.

So, Green Deal, we have a problem.

Feature Image: Majlinda Hoxha / K2.0.

Illustrations: Dina Hajrullahu / K2.0.

Dëshironi të mbështetni gazetarinë tonë?

Në Kosovo 2.0, përpiqemi të jemi shtyllë e gazetarisë së pavarur e me cilësi të lartë, në një epokë ku është gjithnjë e më sfiduese t’i mbash këto standarde dhe ta ndjekësh të vërtetën dhe llogaridhënien pa u frikësuar. Për ta siguruar pavarësinë tonë të vazhdueshme, po prezantojmë HIVE, modelin tonë të ri të anëtarësimit, i cili u ofron atyre që e vlerësojnë gazetarinë tonë, mundësinë të kontribuojnë e bëhen pjesë e misionit tonë.

Anëtarësohuni në “HIVE” ose konsideroni një donacion.