The streets and alleys have remained almost the same through the years. Once riddled with muddy potholes, today the asphalt is bumpy and uneven from heavy vehicles. Driving through these streets can sometimes take on the feeling of an off-road race. But one thing has changed, the humble houses have been replaced with multi-story apartment buildings. Lagja e Muhaxherëve’s desirable location, with direct access to the city center and, has helped spur this rapid construction of high-rise residential buildings.

In many neighborhoods in Kosovo, you don’t have to know the names of the streets. Instead, people often navigate them using the names, origins or ethnicities of the families who initially established the street or neighborhood. Lagja e Muhaxherëve, or the Refugees’ Neighborhood, is one of these places.

The neighborhood was established by families who settled there after the Ottoman defeat in the Russo-Turkish War of 1878. In the aftermath, Serbia gained large parts of what is today southern Serbia and then expelled most of the Albanians living there, many of whom ended up in Kosovo.

According to the history of the neighborhood in the municipality’s zoning plan, the first of these families arrived in Lagja e Muhaxherëve in 1878. Their surnames were often based on the name of the village they had left behind in Serbia. But over time their identity was cemented as muhaxhers, a word that comes from the Arabic “muhajir,” which means refugee.

Sitting on a steep incline that starts from Agim Ramadani Street and climbs up to the grave of the late President Ibrahim Rugova, Lagja e Muhaxherëve is a distinctive neighborhood at the center of the capital.

In the past, the houses — mostly one or two stories — sat almost one on the top of the other as they ascended the hill. The streets wound about, sometimes leading out, but more often leading to a dead-end.

According to residents, the road at the edge of the neighborhood used to be paved with cobblestones and at the top of the hill it was sporadically paved with concrete. But much of the roads remained unpaved. The uneven infrastructure worked well enough for the residents.

In many neighborhoods in Prishtina, high-rise buildings began to be built immediately after the war in 1999. Arsim Gllogu, a resident of Lagja e Muhaxherëve, recalls that construction suddenly started in his neighborhood in 2010. Though the Gllogu family are not muhaxhers (they’re from Batllava), they’ve lived in the neighborhood since 1930. An only child, Gllogu followed in his father’s footsteps and became a blacksmith.

“I have many memories there, so many,” Gllogu said. “The streets have always been closed and narrow, but the hearts have always been open. Right in front of my house there was a slightly wider space, and there the atmosphere was like a stadium.”

After the war, he demolished the old mud brick house the family lived in and built a new one that suited his needs and allowed him to have his workshop nearby.

“The house is 600 square meters. On the ground floor I had my workshop, on the upper floors we had a living room and also had a large terrace. Work, conversations, friends, family, we had everything there,” said Gllogu. “We had a very good social set-up. If someone was in a difficult situation, we all helped. But the construction came and interfered.”

The land in the neighborhood was divided into small plots, so when developers came in to build high-rises, they needed to get a large number of neighbors and family members to unanimously agree to sell. The more contiguous land the developers could secure, the larger and taller their apartment buildings could grow.

But not everyone agreed when in 2017 a company came in and wanted to buy up land in order to build a large apartment. Gllogu says that this was when the harmony between neighbors and families began to break down.

“I had no interest, because my house is in a good position,” he said. “However, I agreed that I would not be an obstacle for the larger project. But then they only offered me 315 square meters worth of apartments so everything ended there. I didn’t give my land or house for construction.”

But the surrounding construction started anyway.

Gllogu brought surveyors to his house before the construction started, so that if something went wrong he would have a professional assessment. As if he had predicted it, when the construction got under way in 2017, the safety pillars embedded in the ground to prevent landslides failed. Prishtina’s municipal inspectors’ office assessed Gllogu’s house as uninhabitable.

The failure of the safety pillars resulted in the foundation of Arsim Gllogu's house to be undermined. Video: Arsim Gllogu.

Gllogu moved his workshop to the Arbëria neighborhood and rents a home for his wife and two sons in the Emshir neighborhood, closer to the city’s outskirts. In the six years since he was forced to leave Lagja e Muhaxherëve, he has regularly visited his old house and marked each new crack, even writing down the dates they appear.

Construction, bit by bit

Today, Gllogu’s house stands alone and abandoned among the new tall buildings of Lagja e Muhaxherëve. The old kitchen, where they had once prepared family meals, is now covered in dust. On one side of the house the foundation has been completely undermined. Some doors no longer open or close because the shifting of the ground under the house has warped the frames.

Gllogu has been in a six year legal battle against the company that erected the building and made his home uninhabitable.

“I want them to secure the soil, and build my house as it was. Nothing more. I will never give up on that neighborhood. All my memories are there,” said Gllogu, who laments the ill fortune that has fallen on him.

“If you don’t give in to them, they will kick you out,” he said repeatedly as he walked down the streets, sometimes greeting old neighbors, who were out watching a building being erected on the plot of land where their houses had once stood.

There is a consistent formula construction companies and landowners use when residential land is being acquired for construction. Usually, there is no exchange of cash.

If the plot is 10 ari (1,000 square meters) and the building coefficient, a zoning designation set by the municipality, in that area is 3, then 3,000 square meters of interior space can be built on that plot. Once the future building’s size is set, the landowners and the developer come to a private agreement in which the landowner receives a percentage of the future building. In our hypothetical example, if the owner asks for 30%, they would receive 900 square meters gross of future building.

After a standard subtraction of 10 to 12% of space due to common spaces such as stairs, corridors and elevators, the land owners would receive 810 square meters of the final building. With apartment prices reaching up to 1,300 euros per square meter near the city center, a landowner who trades in 10 ari of land could receive new apartments with an approximate market value of 819,000 euros.

Not all neighbors or family members agree to trade in their land or houses for apartment buildings though, so developers end up buying up scattered parcels of land piecemeal. But this approach also results in new buildings going up without any central planning and crammed together cheek by jowl.

A common joke is that neighbors are able to change the station of neighbors’ televisions in nextdoor buildings. These crammed-together new buildings are going up in the neighborhoods Mati 1, Arbëria, Emshir and Dodona as well as Lagja e Muhaxherëve.

Holdouts like Gllogu’s house, surrounded by new high-rises, can be found in other neighborhoods around Prishtina, but few of their owners agreed to speak on the record. Most are frustrated by the situation they’ve ended up in.

Architectural engineer Shpëtim Berisha, who has been working in his architecture studio for two decades, highlights this problem, where small investors have built bit-by-bit instead of building as part of a broader plan.

Berisha said that the two main factors affecting urban development have been that multiple small developers are functioning throughout the city with no coordination and limited oversight and that both owners and developers are motivated to build as much square meterage as possible per plot in order to maximize profit. According to him, this has meant that apartments get less natural light and their views have been obstructed. All of this results in a poor quality of life.

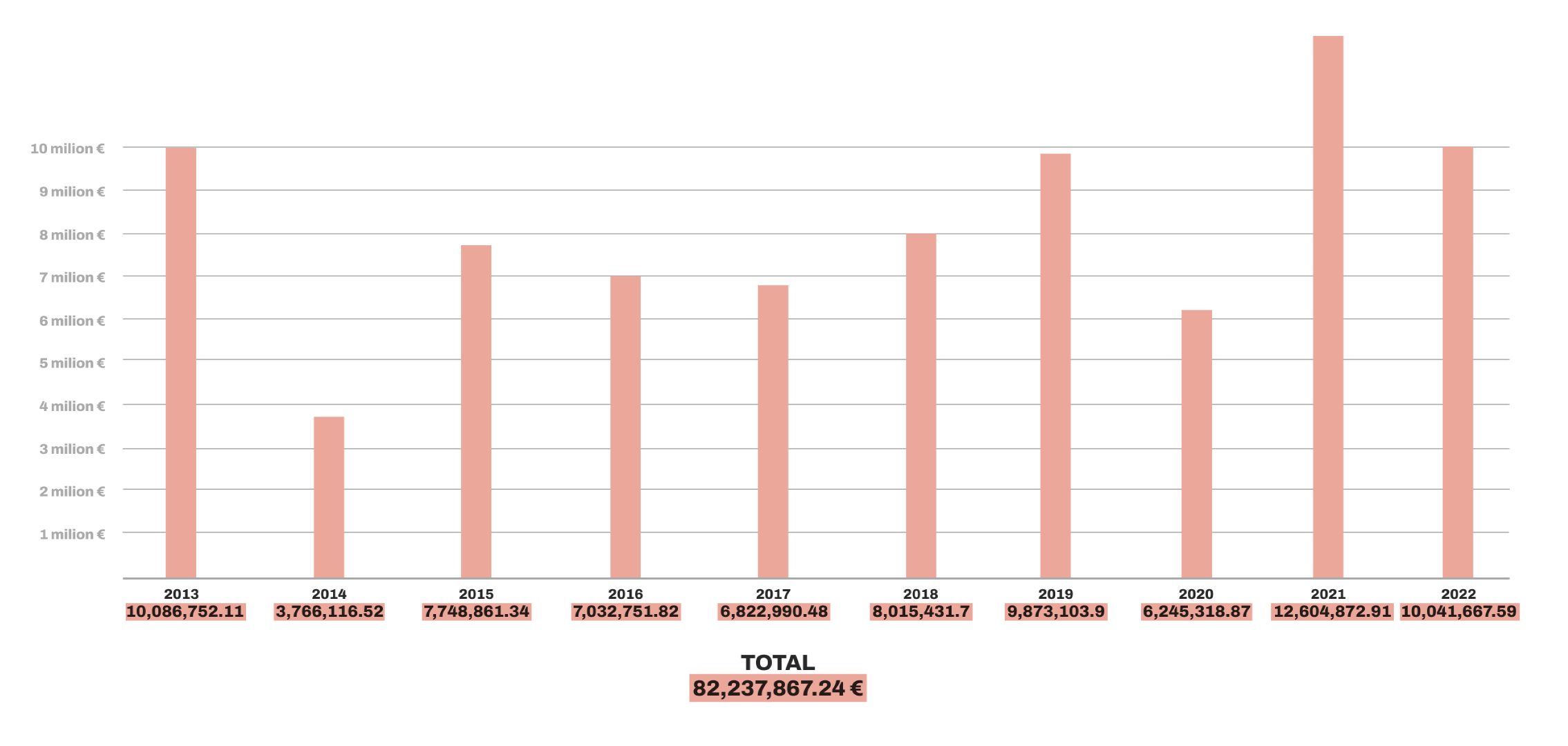

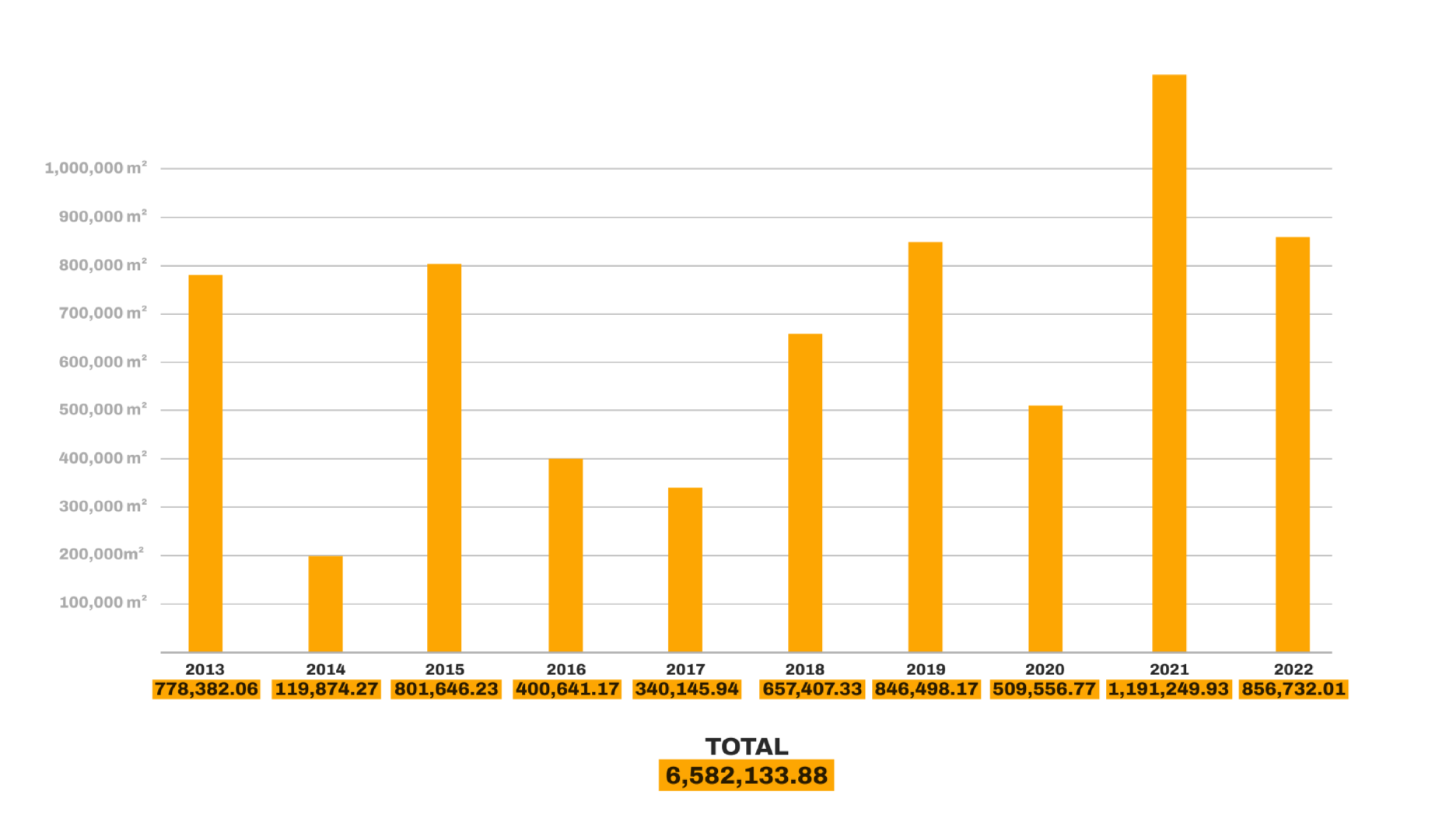

According to public documents from the Municipality of Prishtina, in the last 10 years, not including the year 2023, over 6.5 million square meters of building permits have been granted for multi-story commercial-residential buildings in Prishtina. According to public documents the municipality has earned over 82 million euros from construction permits.

Despite the large amount of new construction, the new buildings are continuing to expand on the outskirts of the city. Prices are high due to high demand.

Today, the minimum price varies from 850 to 900 euros per square meter for neighborhoods outside the center of Prishtina. For neighborhoods in the center or close to it (as well as in the new neighborhoods Mati 1 and Prishtina e Re and the Yugoslav-era neighborhoods Dardani and Ulpiana) the price for a square meter varies between 1,100 and 1,300. An 80 square meter two-bedroom apartment in these neighborhoods will run over 95,000 euros. In a country where the average monthly salary in the private sector is below 500 euros, loans and other financing are usually necessary to purchase property.

One option is to get a standard bank loan. Some buyers get a mortgage and pay for the apartment in full, and then pay off the apartment in monthly payments to the bank. According to data from the Central Bank of Kosovo (CBK), based on the Credit Registry (RKK) system of Kosovo, 535 such residential loans were issued in 2022, and 92 were issued in the first quarter of 2023. Others establish private agreements between banks and construction companies to pay for the apartment in installments in order to avoid having to put down a large cash payment in the beginning.

There are other ways people acquire apartments. Some suppliers, construction employees or contractors are not paid in cash for their work building apartments and are instead given an apartment in the not-yet-built buildings. In order to get cash quickly, these contractors tend to sell off the apartment at cheaper rates.

One reason housing prices remain high despite a massive increase in housing stock is due to demand from the diaspora. Quarterly economic reports from the CBK show that foreign direct investment in 2022 totaled 761.5 million euros, of which 523.3 million euros, or 69%, was invested in real estate.

The old or the new, that is the question

“Old or new?” That’s the question about any apartment in Prishtina. Most buildings can be divided into Yugoslav-era buildings and those built after the war ended in 1999.

Some of the older buildings in Prishtina can be found in Ulpiana. This neighborhood was based on an urban plan conceived in the 1960s by the pioneer of architecture in Kosovo, Bashkim Fehmiu. When the first residents moved into the development in the 1970s, Ulpiana had 10,000 inhabitants, but at that time, the Rilindja newspaper wrote that the urban place for Ulpiana had not been fulfilled since it did not have a health center or a cinema (the latter was never built). In new neighborhoods in Prishtina, health centers and cinemas exist only in marketing brochures. The residents of the neighborhood Veternik do not even have a school.

The history of Prishtina’s neighborhoods shows that the new and the old often do not coexist. To build the new, the old has been demolished.

In the mid-1960s when the city began to develop and grow up through the end of the 1980s, large parts of the old city were demolished. In a tribune of architects and urban planners, which the Rilindja newspaper reported on in January 1978, Fehmiu said that the erasure was a mistake.

“The tragedy of Prishtina, as well as of other settlements in Kosovo, is that the new cities have been placed on top of the old, and not dialectically, as in the new next to the old. This has caused Prishtina to come to a housing crisis in terms of quantity and quality,” said Fehmiu.

Fehmiu, who left his mark on the design of the Ulpiana neighborhood, said that he had given up on the project when he saw that the amount of housing had increased without regard to the original project goals.

Prishtina architect and urban planner Rexhep Luci claimed the same in 1977 when he led the local state-run public housing enterprise.

He noted as a positive example, “the first and second block of apartments [in the Taslixhe neighborhood], which were built as a result of the construction with an urban plan,” in contrast with the “Ulpiana neighborhood, which, under the influence of certain necessary technological needs, was not built as planned,” he said.

From the 1960s to the 1980s, public enterprises and labor organizations constructed extensive social housing partially financed by worker contributions.

Large enterprises such as the Ramiz Sadiku construction firm or the Battery Factory started to build apartments for their employees. The workers applied for an apartment and in most cases priority was given to those who had families. The state also built apartments for education workers, and members of the police and military. Today, older Prishtina residents still refer to some of these developments as the “Professors’ neighborhood” or the “Officers’ neighborhood.”

“Thus, the workplace was the way to access housing,” said Artan Mustafa, lecturer and researcher of social policy in Kosovo and the Balkans. Public housing at that time. Mustafa added, was the ideal of the new socialist life. “They were built with the highest quality for the time, they had water, heating and the best infrastructure around.”

It’s a little known fact that during Yugoslavia, there were also opportunities for individuals to purchase apartments. A February 1977 article in Rilindja notes that a moratorium on new houses had been announced because people had begun building them without regard to the urban plan. Plots of land in the Dragodan neighborhood, now referred to as Arbëria, were available for houses, but reserved for Prishtina families who had been displaced due to municipal projects or roadbuilding.

For some time, the main way to access housing in Prishtina was to acquire an apartment in the Dardania neighborhood that was being built. The state-run public housing enterprise was selling apartments at 7,050 dinars per square meter, which in the dollar exchange rate of the time was $380. The article stated that the purchase of an apartment should be done by paying half of the amount at the beginning, and the other half when the apartment is finished.

Between construction in the Yugoslav era and the post-war period there was a gap. According to Driton Tafallari, housing policy researcher at the non-governmental organization “Developing Together,” in the 1990s when Kosovar Albanians were excluded from the public sector, the Serbian government weaponized the political chaos and started building without an urban plan.

Some of these new buildings, built without permits or adherence to the plan, were erected to house refugee Serbs from Croatia and Bosnia, who the Milošević regime used to try to increase the number of Serbs in Kosovo. Tafallari noted in particular a building — located on Rrethi i Flamurit, the roundabout that serves as the main entrance to the city from the south — that was intended for these Serbs.

The building was never finished and after the Serbs of Prishtina fled during or after the war, Albanians desperate for housing amid the post-war destruction appropriated the apartments. Today none of the balconies, railings or windows match each other, the facade is only partially intact and the building and its corridors are heavily neglected.

The war had a huge impact on the housing stock in Kosovo. According to a UNHCR report, as of November 1999, 40% of houses in Kosovo were destroyed or severely damaged. In order to put a roof over their heads, much of the rural population moved to the cities. Many factors influenced this trend, including greater employment and economic opportunities and more advanced infrastructure.

In the post-war period, countless international humanitarian organizations came to Kosovo to finance the reconstruction of the country. But the need for housing was great and the situation was chaotic. Many individuals took matters into their own hands and began building without permits and without regard to the urban plan.

Some of the urgent demand for new housing was met by a loose array of politically-connected companies that are today generally referred to as the “construction mafia.” These companies rapidly built multi-story apartments — often slapdash and without permits — in between the iconic houses of the Aktash, Arbëria or Dodona neighborhoods.

Mustafa, lecturer in social policy, said that the post-war displacement greatly transformed Kosovo’s cities and resulted in buildings that in most cases do not adhere to modern construction standards.

But Prishtina still had an urban plan and architect Rexhep Luci, who had contributed to designing it, decided to become its guardian. But in standing up to the wave of illegal constructions, he lost his life. He was shot and murdered after a workshop on the architectural future of Prishtina in which he stood against the illegal constructions. One of the evident results is that the city has disorganized neighborhoods without a central plan.

This is not just the case in Prishtina. Across Kosovo, there are more than 350,000 buildings constructed without permits. Some buildings have been granted permits retroactively based on the 2014 Law for the Treatment of Constructions without Permit, but the deadline for filing remains open well beyond the initial plan because few people have registered.

Architect Shpëtim Berisha said that during the post-war period there was no strategic plan for urban development and that as a result cities lack an architectural identity.

Today, various neighborhoods in Prishtina are filled with overfilled cafes, others with grocery stores, others with pharmacies. Berisha says that this is a result of not properly planning for the use of urban space.

“This hinders the development of the economic scheme. It leaves the impression that there is no serious analysis during the drafting of urban plans, and that professionals aren’t included in these plans,” said Berisha, who sees urban spaces as living organisms. In extreme settings, things can metastasize into “urban cancers,” in his words.

According to Berisha, this situation can have negative impacts: air pollution, noise pollution, and overly dense development that can lead to urban stress. All these factors negatively affect residents’ mental and physical wellbeing.

The internal layout of new residential units has not changed much compared to the past, according to Berisha and there is a problem with the inefficient use of space; the same square meterage could be used more effectively.

Today, a two-bedroom apartment with a living room is often 95 square meters. According to Berisha, this is an irrational use of space as the same number of rooms could be comfortably built with as few as 85 square meters. This difference of 10 square meters could increase the price of an apartment by up to 12,000 euros in some neighborhoods.

One clear fact about the housing market is that regular employment is insufficient for acquiring an apartment. Even the combined salaries of a couple are rarely enough. So without taking out a loan, the only solution is to rent.

The long wait for subsidized affordable housing

Leunora and Emin Haziraj, 31 and 34, have been renting in Prishtina together for five years, dreaming of buying an apartment.

For several years, Emin commuted to Prishtina for work while Leunora was unemployed and living in their village near Klina. At the end of 2018, three years into their marriage, Leunora got a job in Prishtina. This added challenges to their daily life as she now also had to commute. Due to the long commute and the birth of their child, they were forced to move to Fushë Kosova in early 2019, where finding an apartment was challenging.

“We found an apartment [to rent] but how were we meant to move in and to furnish it? We moved into a completely unfurnished apartment except for the kitchen,” said Leunora, recalling that at that time they had limited savings. “We only had 1,200 euros, and with that we bought some simple furniture.”

For three years they lived in this partially unfurnished apartment until they decided to move to a part of the city where they would have easier access to basic services such as a health center. But renting the apartment is a heavy burden. They pay about 220 euros a month, an amount that stretches their budget.

He added that they plan to get a loan to purchase an apartment, even though this may complicate their finances. He is hopeful that buying an apartment will make their lives easier, since the 90 square meter apartment they currently rent is not big enough for his family of four.

Vetëvendosje (VV), now leading the government, gained attention with their electoral promise to provide affordable housing for those who cannot buy an apartment under current market conditions. They plan to sell 4,000 apartments at less than market price. These apartments are to be built by the government on public land in the municipalities of Prishtina, Gjilan, Prizren, Peja and Mitrovica.

In VV’s governing program for the years 2021– 2025, this affordable housing project is summed up in three paragraphs which note that the apartments are intended for young couples, female heads of households and public sector employees such as teachers, nurses, police officers, firefighters and administrators. According to the program, the annual cost of the project will be 22 million euros.

The government intends for young couples to benefit from apartments through this program by making a monthly payment of 120 euros over 120 months, or 150 euros over 150 months. This means that 14,400 euros or 22,500 euros one could buy an apartment over 10 to 12.5 years. The government is working on a feasibility study related to the project with the International Finance Corporation (IFC), part of the World Bank Group.

Though the government initially indicated that the cost of the project would be 80 million euros, Prime Minister Kurti said in a March 2023 session of the Assembly that the cost would rise to 200 million euros. He also noted that Prishtina, Peja and Gjilan have responded to the government’s request to allocate municipal land for the project.

K2.0 sent multiple requests for comment to the Ministry of Environment and Spatial Planning about the project’s progress and eligibility factors for the apartments, but has received no response.

According to Tafallari, a potential problem with this scheme is that according to the Law on Real Estate Leasing and Exchange, public land can only be leased for 99 years, which would make it impossible to sell the apartments.

There are other potential ways the state could increase the housing stock. “For example,” Tafallari said, “Prishtina could ask company X to provide apartments instead of paying taxes. If seven floors are to be built, then build nine floors, but one floor belongs to the state, and thus housing stock is created. But bold laws and decision-making are needed.”

Many countries in Europe have similar schemes in order for residents to access affordable housing. For example, the U.K. has had the First Homes Scheme since 2021, which enables the purchase of a first house at a rate 30 to 50% under market rates. It’s intended for those who have never owned a house or who have a lower family income.

In Vienna, Austria, the government often builds housing on public land that is then sold to private companies who manage the properties. Although these housing units are open to residents of any income, nearly half are reserved for low-income residents who pay less than market rate.

Young couples working in Prishtina have loans as an option, or they can wait around for the government affordable housing plan. But over 40,000 students who come to Prishtina every year have to make do with dormitories or rented apartments.

Student housing

Prishtina, as the capital of Kosovo, is the city with the most dynamic housing market. This is also due to the high concentration of public and private universities.

A significant part of the rental market in Prishtina is made up of students who come here to study.

Student dormitories provide an affordable housing option in Prishtina. There are eight university dormitories, built over the years by the University of Prishtina. They have an affordable price of 20 euros a month, but can only accommodate roughly 3,900 students. According to the Kosovo Agency of Statistics, during the 2022-2023 academic year there are 22,000 students enrolled at the University of Prishtina, so at least 18,100 students, not to mention the thousands of students in private universities, are not able to access dormitory accommodations.

The presence of private dormitories, which are more expensive than public ones, shows that there is a high demand for student accommodation. The rent for private dormitories can be as high as 70 euros, and includes expenses such as electricity, water and heating.

However, a large number of students who are looking for accommodation face various challenges in finding a place to settle. The main problems they experience include rising rental prices, discrimination in the housing market and inadequate housing conditions.

Arbesa Morina, 20, an economics student from Rahovec, faces these problems. She has been renting in Prishtina for two years and has lived in six different apartments so far.

For students like Morina, paying rent is a huge burden on their monthly budget. Morina said that this stress also affects her academic performance, since she often has no choice but to pay rent late.

“It’s stressful because we live four or sometimes five people in one apartment. We often don’t coordinate our rent payments for a certain day, since most of us work and our salaries are sometimes late. This creates additional problems and pressure from the landlords,” she said.

The process of finding an apartment is stress-inducing for her, particularly given rent increases after the pandemic.

“We have often been discriminated against by landlords. Some refurbished apartments or ones with new facilities are not available to students, just because we are students,” she said.

Faton Berisha from the company Access Real Estate said that students are discriminated against in the rental market. Though they are the biggest rental clientele, landlords try to avoid them. He added that average rents in the capital have increased by about 100 euros in the last two years, but demand remains strong.

Housing agency advertisements indicate that apartments in the city center have significantly increased in price. The agency where Berisha works has ads asking for 500 euros per month for a well-furnished 65 square meter one bedroom apartment in the Pejton neighborhood. A similar sized apartment of the same standard on Rruga C or near the hospital costs between 300 and 350 euros.

It doesn’t matter if someone chooses to live in a house or an apartment, to rent or buy, using credit or savings. What comes to the fore is the importance of having a roof over your head, and the difficulty of doing so in Kosovo.

Data from the 2022 Household Budget Survey, carried out by the Kosovo Statistics Agency, shows that housing is among the five main expenses Kosovars face. After food and drink, housing expenditures come second. Out of an estimated 8,106 euro average yearly household expense in 2022, 1,137 euros on average are for housing.

According to Artan Mustafa, housing is a social right and an important part of citizenship, yet it is not seen this way in Kosovo.

“Our cultural connection with the private house comes from the huge instability that we have had historically,” he said, using the example of Prime Minister Kurti, who does not own his house.

“The Prime Minister used this to his advantage in his election campaign. But in Kosovo, it is a luxury to be able to live without owning a house or a private apartment,” said Mustafa. Kurti’s social power and connections, his confidence that he will be able to find employment and a paycheck, is the luxury that allows him to not rely on owning a house as a form of basic insurance, Mustafa said.

Mustafa sees the desire of many Kosovars to own an apartment or house as a security measure. In countries like Kosovo, he said, where efforts to ensure people’s well being are limited, residents feel insecure and see property ownership as a way of securing stability.

The Prishtina of today is the result of a lack of planning public space and a failure to ensure affordable housing. The landscape of the city is a mish-mash, buildings crammed together, erected for residents, regardless of whether or not they can afford it.

Feature image: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0.