Arben Bajraktaraj: Peter Handke is a product of the times we live in

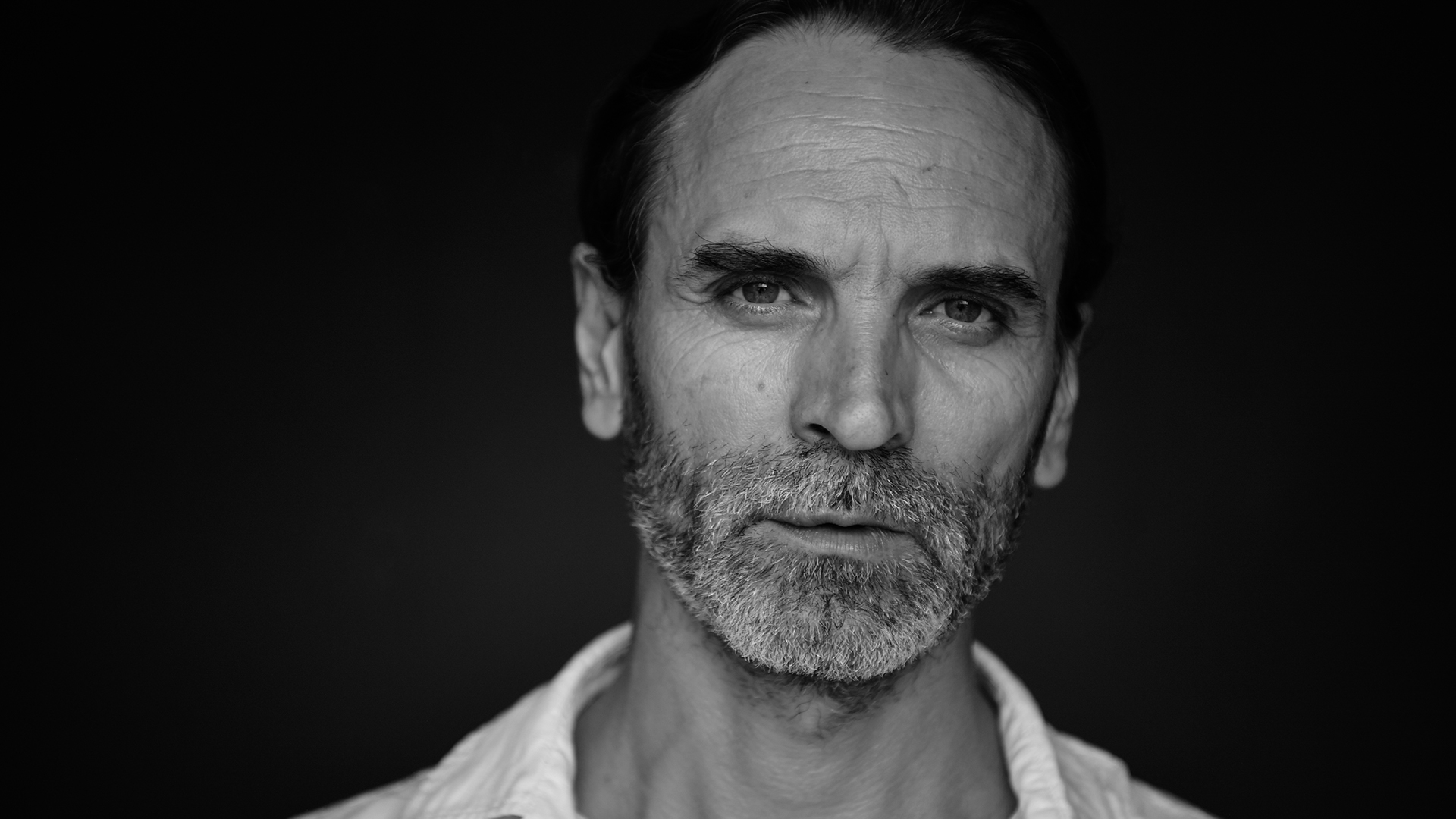

French-Kosovar actor returns to Kosovo's theater scene after 20 years.

The play “The Handke Project: Or, justice for Peter’s stupidities” had its premiere at the beginning of June at the Oda Theater in Prishtina. Written by playwright Jeton Neziraj and directed by Blerta Rrustemi-Neziraj, the play is a fierce denunciation of Austrian writer Peter Handke’s support and legitimization of the Milošević regime’s acts in the former Yugoslavia.

Peter Handke won the Nobel Prize for literature in 2019 and the Swedish Academy praised him “for linguistic ingenuity” through which he “explored the periphery and specificity of human experience.”

With a sarcastic script (for which Neziraj is known) and an alternative directorial approach, the play asks how an author who glorifies the figure of Milošević, relativizing the war crimes committed by the Serbian state in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo, could be rewarded for “exploring the periphery and the specificity of human experience.” Who does linguistic ingenuity serve, when it is used to deny the experiences of victims, distort historical facts and rehabilitate war criminals?

Neziraj wrote in an article for The New European titled “Peter Handke: Literary genius or lunatic genocide denier?” that “It is important to oppose fascism converted into literature […], European hypocrisy, double standards and selective empathy for human pain.”

The show is performed in English and has an international cast. Neziraj revealed that selecting the cast was not easy — some Serbian actors withdrew from the project after taking issue with the content. However, the show was also performed in Belgrade at the Bitef Theater and after the performance Qendra Multimedia issued a statement, which stated: “A discussion has been opened about the Handke phenomenon and the need to liberate Serbian society from its cult. It is being discussed and hopefully it will continue to be discussed.”

One of the actors in the show is the famous Arben Bajraktaraj, who for years has been part of the French theater and film scene and other international film productions. In recent years, a Balkan audience has followed him in the Serbian crime show Besa and in the movie “A Shelter Among the Clouds.” For Bajraktaraj, his role in “The Handke Project” marks a return to the stage of the Kosovar theater scene after almost 20 years. “It is an old longing. But besides that, it’s artistic interest. The theme of the drama was so bold, unusual, not easy,” he said.

At the beginning of October, at the 52nd edition of the Theater Festival in Ferizaj, Bajraktaraj was awarded the award for best actor for his role in “The Handke Project.” The show received three other awards, for the best show, the best directing (Blerta Rrustemi-Neziraj) and the best costume design (Blagoj Micevski).

The play is a production of Qendra Multimedia in collaboration with Mittelfest and Teatro della Pergola (Italy), Dortmund Theater (Germany), the Sarajevo National Theater and the International Theater Festival “Scene MESS” (Bosnia and Herzegovina). It has been shown in various theaters across North Macedonia, Serbia and Italy. This year it will also travel to Bosnia and Herzegovina and Germany. Meanwhile, the show will be performed again in Kosovo at the Kosovo Theater Showcase, which will be held in Prishtina, from October 25 to the 30th.

K2.0 met with Arben Bajraktaraj after the premiere of “The Handke Project” in Prishtina, to talk about his performance and his return to the Kosovar theater scene, politically engaged theater and his father’s library where he read as a child.

K2.0: The show “The Handke Project: Or justice for Peter’s stupidities,” returned you to the Kosovar theater scene after almost 20 years. How did you decide to be a part of the show?

Arben Bajraktaraj: Honestly, it was a bit of a coincidence. Jeton and Blerta visited me in Paris some time ago and came back home with me. While we were talking, after two or three glasses of wine, Jeton and Blerta started to ask me, “Would you be able to come?” I said, “When?” I looked at the dates, right there.

It was an old longing. I regret the fact that I didn’t have the chance to work with Bekim [Lumi], it was a mutual wish. Actually, we worked together once, but it was in Paris. I replaced an actor in his show, Galani, who could not come for very specific reasons.

This is the second time I have come to Kosovo for the theater. The first time was in 2003. There we met with Jeton and a friendship was born. We can say that a kind of movement has been created, which Bekim along with “Loja” [theater magazine published during the years 2006-2010] pushed forward a kind of mutual respect and love for each other’s work. Years have passed, then I said to myself, why not, if not now, then when? The years are passing by, time is running out, we have gray hair now.

In addition, it is an artistic interest. The theme of the drama was, I would say, so bold, unusual, and not easy. Perhaps this was what attracted me the most to the project.

Having its center the question of the relationship between artistic freedom and historical truth, the play is deeply political. What do you think about politically engaged theater? Do you think that in certain situations the theater should speak with a clear political voice?

I think it’s not just an obligation. It is almost a kind of mission to make the voice of the victims be heard. Since the time of the ancient Greeks, in ancient tragedy, Aeschylus, Euripides and others, they were the first to write about the Trojans, who were the enemies of the Greeks, and gave them a voice. In a way, their act was political for the time.

It is imperative in this generation to make things clear. At least, we in Kosovo should present that, this how things are, this is the truth, our truth. To also let Handke know that we also have the right to speak. You will listen to us, won’t you? Believe me, he will listen to us. Few have dared to say things to him face to face, just because in Europe they consider that he deals with art and in art one can do whatever one wants. So, he spits on victims? Aha, alright sir, then we can spit on you too, on behalf of the victims.

The play is read as a criticism of the Swedish Academy, but also of certain European cultural circles that, in one form or another, have embraced and rehabilitated the figure of Handke and his positions on the Milošević regime.

I think there is a complete ego-centrism in the west. They only look at themselves and thus do not see the other’s suffering. Handke is a product of the times we live in, which means he is not alone. It was Renè Girard, then others, who were Handke’s predecessors, raising theories that Bosniaks in Sarajevo killed themselves and blamed the Serbs. As you know, the same thing happened later with the massacre of Reçak. The same system continues today in Bucha, Ukraine. It’s the same theories, the same tactics.

We denounce this. Because in the end we don’t care about Handke and the others as such. People in the west, the Swedish Academy, seem ignorant. But they are not ignorant. We must denounce this. The award was intentional. As if they want to reward controversialism. But he is not controversial, he is the dictator’s ass-licker. And, it is “controversial” to be the ass-licker of dictators. Therefore, “he should be rewarded because he is controversial.” Hah!

This year, the show will first travel to Skopje, Belgrade and then to Italy. [The interview was conducted before these performances]. In autumn, it will return to Prishtina, to continue in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Germany. How do you think it will be received by the public in these countries?

Here, during the premiere in Prishtina, it was extremely well received. And I am convinced that it will be extremely well received in Belgrade as well. In Europe, I believe it will be a surprise, one that they will not expect at all. They are convinced that, “Not at all, Handke didn’t do anything, he just said a few words, just that.” Believe me, it will be a pretty big surprise there, because I was present in France, in the great debate when the director of French comedy removed a play by Handke from their repertoire and there was a big conflict. I personally know authors who argued among themselves — one who was in favor of not removing the drama and the other who was in favor of removing it from the repertoire, and from that day on, they no longer speak to each other.

Our show is very analytical, deeper in the sense of factual exploration of events. It’s very real. We have a lot of chorus — shared scenes, when one character is played by six actors themselves — so it is essential to be together permanently, because if one connection falls, we all fall.

We have been watching Handke’s interviews for a long time, where you can see his way of expression, which is much more grotesque than what we do in the show. So I believe and hope that there will be a shock among these fiery European intellectuals, who endlessly love freedom of expression even when that freedom spits on the victims.

You have mentioned that two of the main professional references for you are the English director Peter Brook and the French author and actor Antonin Artaud. Both are from the theater world. Why these two?

For two reasons. Brook because when I went to Paris for the first time in 1996, a few months later I was lucky enough to see one of his shows that remained in my soul and mind. I was impressed by the simplicity of it. It was with only four actors. It was called, “The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat,” by the British author Oliver Sacks.

I was amazed how four people could, with nothing, just a carpet and interpretation of the text, keep us that excited. For two hours, we breathed the whole time with them. Then there were other shows, but this was what brought me back to the base of the theater. Indeed, it reminded me of our men’s oda, because there a man tells a story, or sings a rhapsody, which can go on for up to six hours. This is what I wanted to say — the essence of theater.

Artaud is another reference. Thanks to Bekim [Lumi], who asked me to translate Artaud’s book, “Le Théâtre et son Double,” [English: The Theater and its Double], I embarked on a three year study of him. Perhaps Artaud opened my eyes to a completely different approach to theater, which is connected to the roots of intergenerational memory and a strong connection with nature and everything that surrounds us in this universe. One of the main articles in the book is “The actor and emotional athleticism,” or the actor’s emotional preparation as an athlete, which for me is essential in building any character.

What is meant by emotional athleticism?

First of all, the opening of the range, both physical, mental, but also organic. The wider the palette, the more opportunities you have to give spiritual life to the characters. There have been a lot of psychologizing approaches. There has been a misunderstanding since Stanislavsky [Russian theater director, known for his system of training actors]. People have interpreted it as they thought. However, he had his own approach, which works for some and not for others. For me, Artaud is more essential, because he connects us to our antiquity, which is not the case with Stanislavsky. At least from what I understand.

I am very attached to rituals. Perhaps due to the fact that we went to the mountains in the summers, the connection with nature was very direct. When I say the connection with nature, I mean when you face a bear really in front of you and you experience fear as a real fear. I think that every experience, every moment, as Borges says, is unrepeatable.

During your childhood you read a lot of literature, especially when you stayed in the mountains. What did you read?

I didn’t have anything to do. We had no electricity, no television, and no internet at that time. Even today, in our mountains, the phone doesn’t work well. I hope they haven’t put antennas up there.

Dad was a professor and luckily we had a lot of books at home. Since then, I started reading Albert Camus and novels that were not for my age, because I used to read in my father’s library. Then, there was also Albanian literature. Then as a child, I read all the works of Sterjo Spasse, like everyone at that time. I also remember “Orteku” by Rexhai Surroi and of course Charles Dickens, all the literature that was for my age. I’m talking about ages eight to 14. I also read Dostoyevsky at that time, which was not for my age. But I understood it later, so I re-read it.

I remember “Crime and Punishment.” I was 14 years old and I went to the Deçan library. At that time, they had started firing the Albanians from their jobs. An Orthodox priest was there. There was no one there. But, the books in Albanian were there. I went there to get Dostoyevsky. The priest was pleased, his face lit up. I spoke to him in Albanian and then he frowned.

One of the most emblematic scenes in the show is when you, wearing angel’s wings, confront the character of Peter Pan, where you also act in the German language.

This is an homage to a screenplay that Handke wrote with Wim Wenders, called “Wings of Desire” [original title: Der Himmel über Berlin]. It is one of the strongest scenes. Bruno Ganz plays the role of the angel. Personally, it is a tribute to Bruno Ganz, because for me he is one of my reference actors. I had three reference actors during my growth and acting journey: Michel Piccoli, Bruno Ganz and Bekim Fehmiu.

I think Jeton wrote it really well, but I found the phrase in German and I wanted to perform in German to be a spiritual homage to Bruno Ganz, who for me is a great actor.

During your career, you have acted in many languages. The Handke Project is mostly in English, but there are fragments in Albanian, Serbian and German. How is it for you to act in different languages?

The only thing that I probably regret a little, is that I came to Kosovo to act in Albanian. But when I came here, they told me that the show will be in English. Later, I found out that the show would also be performed in Europe and that there is an international team. But it changes organically. I mostly enjoy acting in Albanian. When I played Albanian for the first time, in 2003, it seemed much simpler. Even one’s voice does not transmit the same when playing in different languages, because language is not only language, it is also a way of being. But there’s something beautiful about switching from one language to another. I’ve been lucky enough to play in dozens of languages, even ones I don’t speak. It’s also interesting, because you have to catch the melody. It requires seven to eight times more work.

What other projects are you working on?

I am filming a series in France for the French TV station TF1. Then there is a feature film, also in France, and a theater show that we play in September, by the Albanian director, Simon Pitaqaj, very dear to me, with whom I have worked together for a long time. The play also stars Denis Lavant, who is one of the greatest actors of the French theater today. We will perform Dostoevsky’s “Dream of the Ridiculous Man” in the theater of Paris. These are on the way. But it was a great happiness to come and work in Kosovo.

The content of this article is the sole responsibility of K2.0.

Curious about how our journalism is funded? Learn more here.