We watched it hit Italy. We watched as most of Europe went into lockdown. Then we watched as COVID-19 arrived here, in Kosovo.

And everything went fine.

We stifled the number of new cases, quarantined, traced contacts and shut ourselves away. We protected our health, protected our parents and grandparents, protected our fragile health service. We did it!

Or so we thought…

Five months later, and we’re back at number one. But this time, for all the wrong reasons. Now, we can often be found near the top of lists of countries ranked by COVID-19 death rate.

And our healthcare system, which was already a mess, is approaching breaking point.

More than 1,200 health professionals have been infected, while seven doctors and five nurses are reported to have died.

As the crisis continued to escalate in July and early August, I set out to document the COVID-19 frontlines.

The Three Musketeers

Raif Hasani’s younger colleagues call him Haxhia. It’s accurate too, as he has completed the hadj (pilgrimage) to Mecca in the past. He’s one of three National Institute of Public Health (IKSHPK) technicians that I’m embedded with for a couple of days.

“On that day, when we got the first two cases, it was Friday 13,” Haxhia recalls, thinking back to the March day that the virus arrived in Kosovo. “A friend called: ‘Raif, is this a coincidence?’ he joked.”

Haxhia laughs at the memory, knowing well that there was nothing superstitious about it and that it was just a matter of time until Kosovo confirmed its first case. “We’d been conducting PCR tests since December,” he tells me.

He’s part of a team of three, who I start to think of as the Three Musketeers. There’s Kastriot Maraj (D’Artagnan) the youngest and lead guy — in this case, the actual boss. Then Hasani (Athos) the oldest, who is protective of his younger colleague. Finally, there’s Mirsad Kasumi (Porthos) dedicated and reliable, though unlike Porthos, Mirsad is shy.

It’s clear that the three are a team — a task force. Haxhia praises the team leader (even though it’s him who’s completing his master’s degree) and points to the achievement of a young guy from Istog completing Sanitary Medicine. The bond is beyond academia.

For today’s field work, we’re heading to the publicly owned water company, Ujësjellësi i Prishtinës to carry out around 50 tests.

Before we set out, Kastriot is careful to disinfect the whole car, and when we arrive a whole new round of disinfecting begins. It’s clear that the boss knows his stuff from the way he disinfects everything. Haxhia nods his head to indicate that I should just follow his lead.

He suits me up so I look like one of the SpaceX astronauts. It turns out this is the easy part — getting out of the suit later is a whole different procedure, as it’s here that the chance of infection is high.

He then sprays me with strong alcohol disinfectant, before repeating the same procedure with Mirsad, and finally Haxhia, who stands like a statue throughout. After so much spraying, the air carries a distinct smell of loza (a strong alcohol grappa made in the Balkans). They later explain that the alcohol spray was a donation from one of the wineries in Rahovec who had provided the excess from their wines and raki production.

As we enter the facility, Kastriot notices a couple of old guys not wearing masks, and scolds them like a dad, telling them to put their masks on — they do.

Inside, they again disinfect the hell out of everything, before they get to work conducting their tests.

The workers seem to get a weird feeling seeing the arrival of the Three Musketeers (or is it four now, with me as Aramis?). But the leading characters have their system by now. After all, they’ve been doing this for months.

The procedure is a relatively simple one — a long swab is inserted into one of the nostrils and eased slowly through it to the back of the throat. After a few seconds of rotating it around a bit, they carefully withdraw the swab, place it into a sterile container and record it.

Then, repeat.

After about an hour, they’ve completed all the tests at the water company and we take them to be analysed back at the Institute. It’s here that they’ll continue their shift, testing suspected cases.

There are plenty of them to test. It’s just been revealed that in the past two weeks, Kosovo has had more new COVID-19 cases per 100,000 population than any other country in Europe.

Over a quick coffee break we get a better chance to talk, though Mirsad has his tea and heads off to finish up some other work. He seems to be one of those guys who doesn’t like to leave things until their deadlines; he’d rather just get them done.

As we watch doctors moving in and out of a nearby bar on their 5 minute breaks, I ask Kastriot about the hardest thing they’ve faced so far. “We were heroes for a few months,” he replies. “Then later we got called incompetent or [criticized] for not delivering on time.”

He’s a strongly built guy, blonde with big blue eyes. Half hiding beneath his sleeves are tattoos, hinting at being one of Istog’s cool guys.

As we talk, he tells me that his dad was a professor of chemistry and physics. His brother used his brain to emigrate to Sweden, but Kastriot wanted to use the scientific knowledge he picked up from his dad to be one of the proud doctors or nurses in Kosovo.

As I try to ask him more personal questions, he deflects, giving me medical explanations that I have heard before and am not really interested in right now. His professionalism is hard to penetrate; to him, this is his job, his responsibility. He doesn’t seek any glory.

But I’m interested in his story; a guy who we valued as a hero just months before but who became caught up in the anger of the population as the political situation changed. I ask him about the first day — he doesn’t remember, his days have blurred and become one.

Then I ask him about his family and his kids.

It’s now that his big blue eyes turn red. It’s subtle, something I’ve seen before in blondes, especially when they’re tired or have had too much to drink — but this was different. I realize he’s holding back tears.

He explains that he’s not been able to be with his newborn daughter for months, just coming near the window and saying hi. No touching, whatsoever. Not able to hold her in his arms. Why? Because her dad is on the frontline of a global pandemic… the guy is exposed.

That’s when he realizes how serious it is. And he can’t hold it in.

We meet again a couple of days later. There has been a positive case in the old peoples’ home in Prishtina.

I meet them at 14:30, having gotten my sleep in. But they’ve been on the frontlines since 7 a.m. sharp, and tell me they’ve already carried out 200 tests. They’re about to do 140 more.

They’ve been in this place plenty of times before, carrying out various tests required of the National Institute of Public Health, so they already know some of the residents — those who are still alive.

Kastriot reminds me of my mother as he turns into my boss for the day: “Atdhe, we’re gonna really gear you up this time, big time…” He takes control. Haxhia waits for his instructions.

I’m suited up like normal, but they give me double gloves — taking extra care of me.

First, they test the staff, before heading to the residents.

Most of them are very old and I feel like many are just waiting for their god to take them. They’re of mixed ethnicities; Albanians, Serbs, Croats or a combination — but all left with nobody but the state to look after them in their old age. Some have found a partner in the home, out of convenience or love. Who am I to judge? They’re older than me.

The facility has three floors, so Kastriot ensures there’s a testing station on each level. They come one by one for their tests. Then we go room to room to test those that can’t get out of bed.

About three hours later, they’ve managed to test everyone, and I’ve got my images.

We leave the premises and carefully get out of our protective suits. I offer to get the guys a coffee, but they thank me with a smile and tell me, “No, you go and enjoy your coffee — we have more tests to conduct today.”

Three days later, I find out that 31 of the elderly residents and nine workers had tested positive for COVID-19.

An ongoing emergency

I visit the microbiologists at the institute. They spend their days in the lab, carrying out the analysis of all the COVID-19 tests.

Zana Kaçaniku-Deva has worked at IKSHPK since 2016, but the nature of the job has changed in recent months and it now has a new rhythm.

“My days have been the same since February or longer — they’re the same,” she tells me. “I wake up to calls from doctors, asking me about the results of their cases, those for deceased people [who have died before they received their result] or for those in grave conditions — and they ask for them urgently.”

Just like the technicians in the field, they have their systems set up as they’ve been doing this almost non-stop since the turn of the year. The samples pass through a number of rooms, pieces of equipment and staff members’ hands before the results are known.

To begin with, Zana was one of just two microbiologists in the team — working alongside the technicians and other staff — but now there are five. She says this is more manageable, especially since the cases have been on the rise.

Zana tells me there are always emergencies with certain cases that need to be processed extra quickly.

“The day never ends, even though we have our daily plan,” she says. “But with the situation as it is — it’s an emergency, we get it. And we keep it up.”

Zana’s a mother of two, and I ask if her daughters see their mom as a heroine, working extra shifts to do her part in trying to deal with the COVID-19 situation.

“Thank God they are adolescents, both of them — they are skiing competitors,” she says, before flipping my question on its head. “They are my heroines,” she says, and tells me that her younger daughter had achieved first place in a race earlier in the year.

I ask her about her toughest day over all these months. “Too many days,” she says, before turning to her colleague, Blerim, who she’s on duty with today. “Which day, ah?”

Then she finds the closest one she can recall. It was a week earlier, when five people had died at the clinic after the oxygen malfunctioned.

“It was tough. We thought about our kids, parents, the overall population, also keeping in mind that our health system has a lot of flaws,” she says, explaining that it caused a lot of doubts and questions.

“Can we keep our professionalism up? Can we serve everyone? How is it going to play out?”

Once we get outside the lab, Zana takes off her mask and visor, and I see who I’ve been talking to for the first time. Her hair is short and blonde (practical for her job) and it has been flattened by her protective equipment; her eyes look tired with dark rings beneath them after months of stress.

She has stains and sweat on her face, just like in the images of doctors that we saw coming from Italy in the early days of the pandemic back in February, but she still wants to look beautiful and proud.

The situation in Italy seems to be getting better, for now. Its cases were way higher than those in the Balkans to begin with, but cases across the region — and Kosovo in particular — are now on the rise and the deaths per capita numbers are climbing.

Into the inferno

At the start of August, I receive permission to enter the Infectious Diseases Clinic. This is where shit really gets real.

In the time I’ve been waiting for the clearance, the death toll has kept going up. In the past few days, we’ve regularly seen more than 10 per day and there’s a sense that the situation is deteriorating day by day.

I call the clinic’s director and head epidemiologist Dr. Lindita Ajazaj. She tells me to suit up and come up to Section B. I follow her instructions.

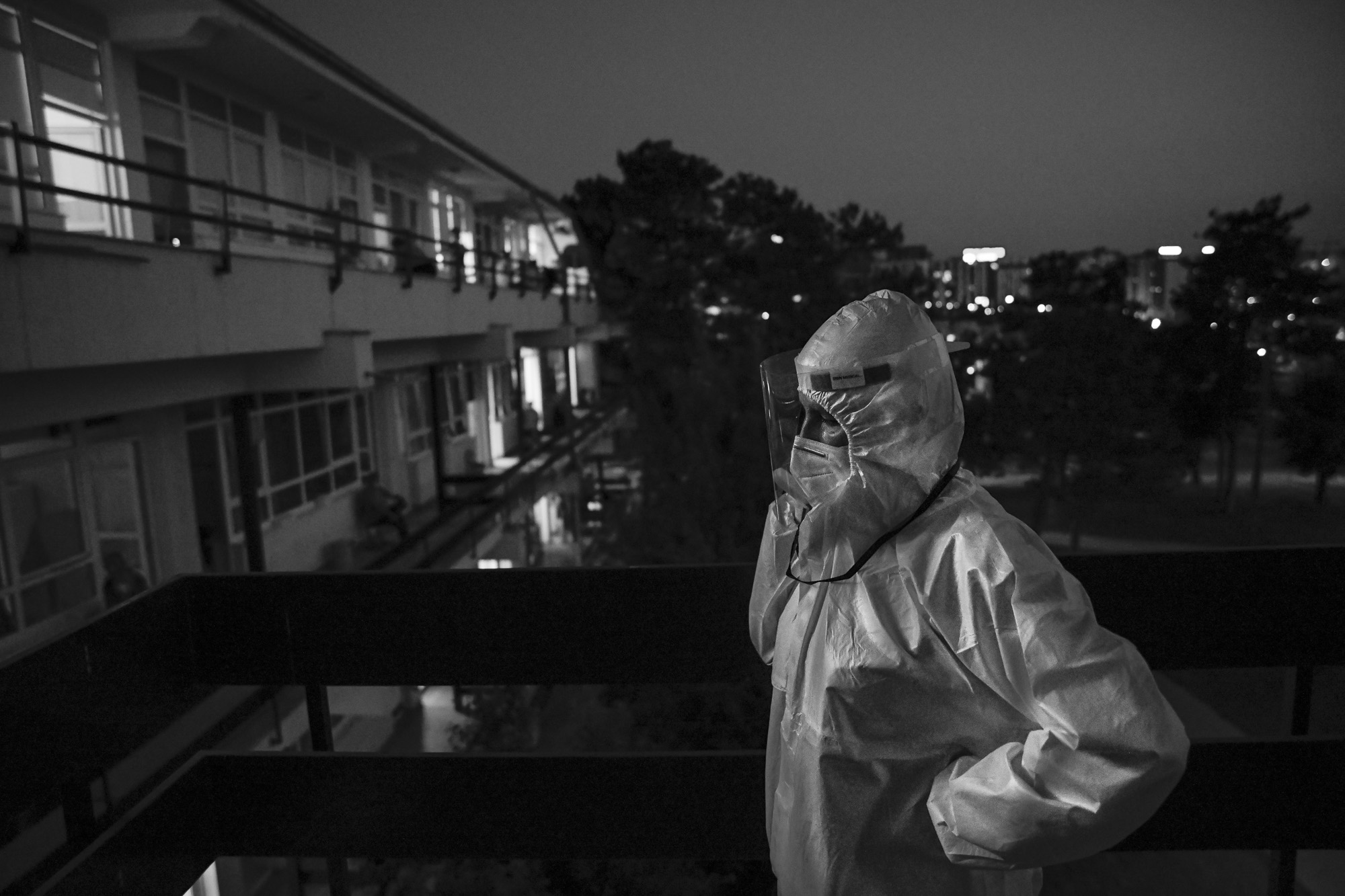

Dr. Lindita is in the middle of a 24 hour shift. I find her in an outside stairwell and without ceremony she immediately tells me to follow her. She’s conducting her routine check ups.

We’re on the first floor of the clinic’s three-floor wards, walking around the balconies that connect the rooms so, as much as possible, we can stay outside where the air flows. I see a lot of family members waiting on the balconies outside the rooms, understandably staying close to their loved ones.

Like the doctors, I’m again in my NASA suit. The doctor takes care to make sure my mask is on properly before we enter the first room.

Inside, there are two older guys, who I ask permission to take their portraits. “Go ahead, shoot — we’re survivors,” they laugh. Both are connected to oxygen masks and they’re clearly not in the best of conditions, but their spirits are up, feeling good that at least somebody is looking after them.

But this isn’t the case in the other rooms. As we continue, it just keeps getting worse.

In every room you hear the sound of machines beeping, measuring heartbeats and blood pressure, as well as oxygen bottles for each patient that’s panting as though they’ve been running or are exhausted.

Some patients are very cooperative with the medical staff, knowing their fate is in their hands. Others are more agitated, wanting more attention — they’re clearly in pain.

I speak briefly with a young medic who’s standing in the balcony doorway keeping a record of patients’ vitals, including their oxygen saturation levels. He tells me he’s into the 13th hour of his shift.

We go from room to room, working our way through the building, from the first floor to the second, then the third. Everywhere, it’s the same sight.

Some patients are sleeping, others are awake. I can’t help but notice that in some rooms family members are in tears over their loved ones.

The patients are from all generations; old and young. But one thing that the vast majority have in common is that they’re hooked up to oxygen bottles. This place reminds me more and more of some living hell.

And the clinic is almost full — I see just a handful of empty beds and wonder how many of them had been vacated by patients who hadn’t made it through the night. The daily briefing had told us 13 COVID-19 patients had succumbed in the past 24 hours; another seven deaths would be announced today.

We reach the last room of Section B, up on the third floor — the last stage of the inferno, or so I thought.

I’ve been in the clinic for 3 hours and I’m already feeling tired, especially as I’m not used to working in these protective suits, and I’m struggling to see much when I take my photos as the face shield fills up with condensation. I can only imagine what the doctors and other medical staff must experience, being in those suits for sometimes up to 24 hours at a time.

As I’m getting out of my protective suit and thanking Dr. Lindita for letting me in to document the situation, she smiles at me and signs off in her no-nonsense, military tone that leaves no room for misinterpretation.

“Have a good night, Atdhe,” she says. “We’re heading to intensive care.”

Editor’s note: Photographs were all taken with the permission of those in them or with the permission of family members who were present when this was not possible.

This article is part of the Human Rightivism project, which is funded by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA), implemented by Community Development Fund through its Human Rightivism Program. The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA).