Inheriting a prominent leftist family legacy, my ideological course seemed set. But mugged by Kosovo’s reality, I’ve long sought answers of my own.

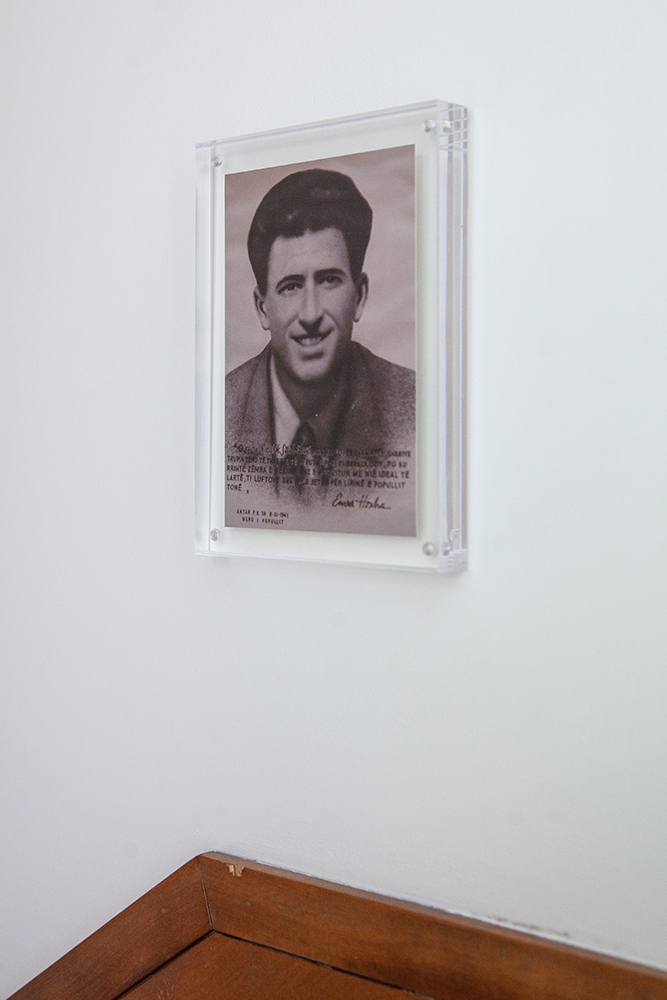

Every day of my childhood, as I walked down the stairs from my room in my two-story house in Prishtina’s old town, I’d face the framed image of my grandmother’s brother hanging prominently on the hallway wall. It contained his cheerful grinning face, and below it an inscription by Albania’s communist leader, Enver Hoxha, pronouncing him a ‘Hero of the People.’

Sadik Stavileci, a 27-year-old Kosovar Albanian from Gjakova who had been educated in Italy and was part of the earliest Albanian communist cells, was killed in 1942 in an ambush by Italian fascists in central Tirana, alongside two other comrades. Their martyrdom holds a prominent place in Albania’s communist mythology. But it also featured strongly in family mythology, where among older members Sadik had the status of an icon.

According to the (likely overblown) family narrative, Sadik was not just a martyr, but also someone who had had a premonition of what was to come with Hoxha. Having been an early critic of Hoxha’s in the communist movement, he would later be denied a more prominent place in historiography by the famously vindictive totalitarian leader.

Many families have binding mythologies centered around origin stories or struggles by such prominent members — the kind that give its younger ones a narrative sense of ‘who we are.’ Some family narratives, for example migrant ones, may end up shaping people’s life choices, or even defining their identity and sense of purpose.

At times, family mythologies have a narrative tension: parents from different ethnicities or regions, or even conflicting ideological camps. Ethnically and religiously diverse settings like the former Ottoman domains or Yugoslavia are full of stories of multiethnic families tormented by later political disintegrations.

Yet frequently — as in my family’s case — family histories can also be rather monolithic and firmly entrenched in a specific outlook on the world.

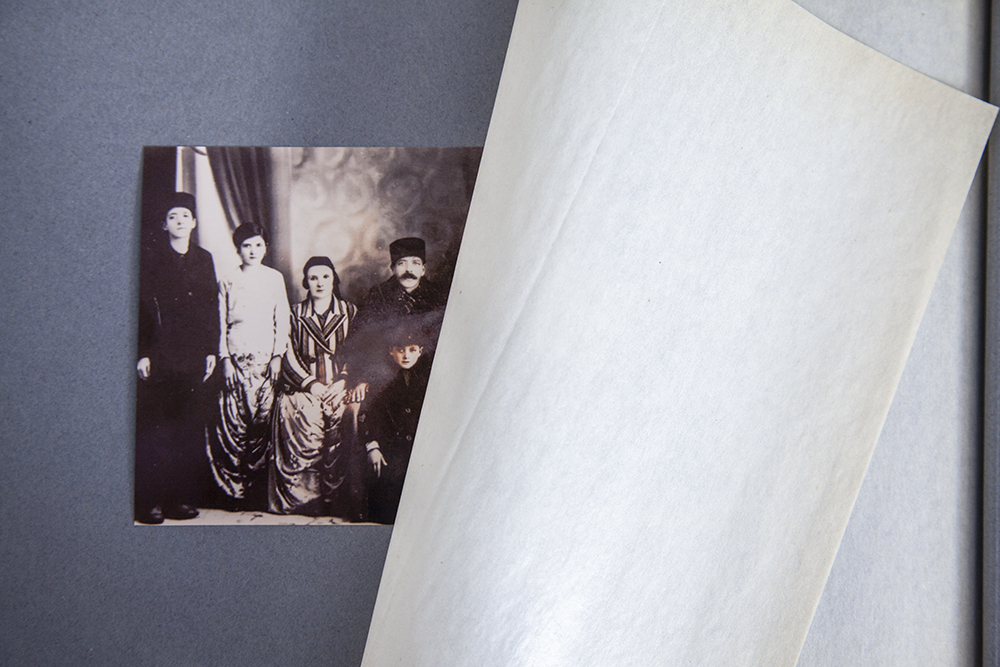

Look back two generations and, save for my half-Bosniak maternal grandmother Umihana, what you’ll find is the same type of Albanians from Kosovo’s multiconfessional and multiethnic Ottoman towns (‘Kasabali’) who like Sadik Stavileci became communists and Partisans during WWII; and later, as these Kasabas grew into socialist industrialist towns and the political context changed, their children became social democrats or human rights activists. Despite the many upheavals and multitude of contexts rarely recognizable from one generation to the next, nobody in my family’s lineage ever left the spectrum of the ideological left.

On the shoulders of revolution

Growing up in the ’80s and ’90s in Prishtina as the Yugoslav wars were unraveling, this leftist family legacy and the struggles of its characters provided a ready-made moral framework from which I would view the world.

Even more prominent and closer to home than Sadik’s story were the risk-taking underdog stories of my own grandfathers, who fought on the other side of the border (though inexistent at the time), alongside Yugoslav Partisans.

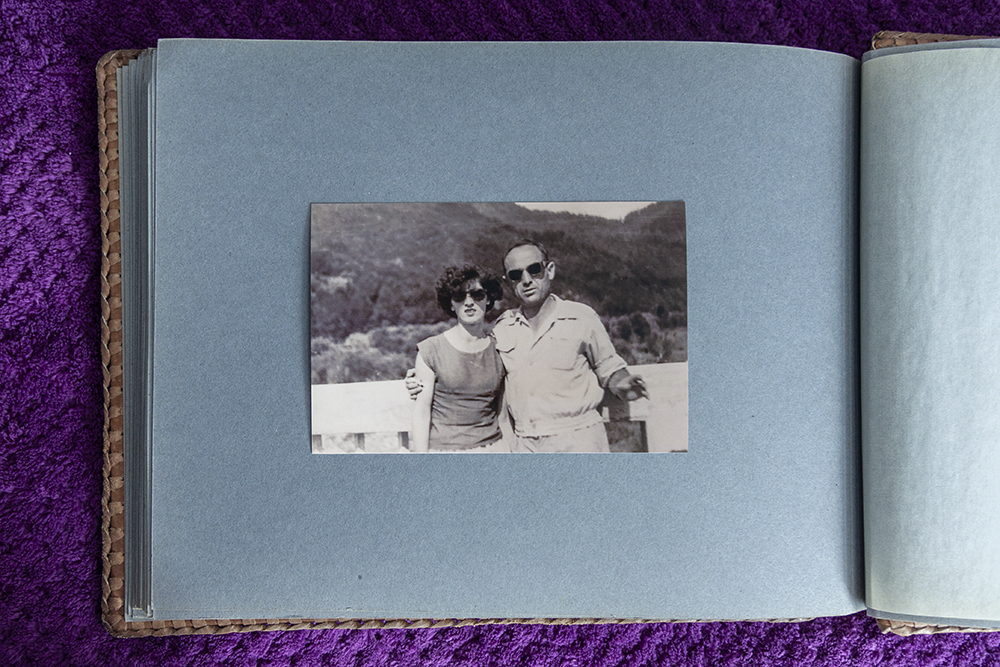

My paternal grandfather Mehmet was an orphaned child laborer from Prizren with only a basic level of education, which he compensated for with immense street smarts and grit. He made ends meet working at bakeries in his hometown and in Skopje, before joining the Partisans and losing an eye in a battle with the Nazis. Romance and ideology overlap here in family lore as Mehmet, part of a Partisan brigade in the Albanian Alps, finds out that a woman he sees there supporting Partisan efforts, my grandmother Remzije, is the sister of his martyred hero Sadik Stavileci.

Even the big question of God was resolved in atheist terms by my grandfather Mehmet’s views.

Mehmet’s fighter and strongman personality (he later became a top security official in Yugoslav-era Kosovo) was complemented on the other side of the family by the stories of sacrifice surrounding my maternal grandfather Fejzullah, another orphan raised by cousins in Gjakova. Fejza was also a Partisan, but engaged on the ‘soft side’ of the post-war revolution as one of the first Albanian-language teachers and an early champion of education, then later in journalism, mostly as a foreign affairs editor at Rilindja and Radio Prishtina. I remember feeling inspired by the tales of how, in the immediate post-war period, Fejza survived three assassination attempts by angry family members of girls, whom the regime was mandating to go to school for the first time.

My communist grandparents had been part of an effort to usher in a new world that marked a fundamental departure from the past. Even the big question of God was resolved in atheist terms by my grandfather Mehmet’s views, which seemed radical for the religiously conservative Prizren of his time and which estranged him from parts of the family. Asked by his curious children to explain what God was, family legend has it that Mehmet’s dialectical materialist answer was: “God is to not steal and do bad things!”

When my father was born in 1947 on the Islamic holiday of Bajram, Mehmet was away on military duty. Upon his return, he disapproved of the family’s decision to follow custom and name his son Bajram. He preferred Shkëlzen, the name of a mountain in the nearby Albanian Alps. “Dear God, what kind of a peasant name is that?” was the reaction of his Kasabali family members from Prizren, a town where Turkish was still the lingua franca signifying higher social status, and where Albanians were supposed to have only Turkish or religious names.

The new world that was being built was one in which social emancipation went hand in hand with national emancipation and secularization, which was reflected in the widespread Albanianization of names over the succeeding generations.

Having been born into this new world that my communist grandparents helped shape, and witnessing the new struggles of my parents’ generation — my father was a leading democracy activist and one of the founders of the Social Democratic Party, my mother Alisa was active in the feminist movements of the time — I was imbued with a sense of core values and beliefs that were not up for question. The answers to a just society were on the left, not just because they brought emancipation and progress, but also because this is ‘who we are.’

Cognitive dissonance

Yet, if the ideological answers were already there, ready to be willed into reality by our human agency, by the time I was a more conscious teenager, many of them were not making sense with a reality that I was trying to comprehend through lenses of my own.

It was June 1998, the war in Kosovo had begun after a decade of apartheid, and a genocide in Bosnia had already occurred. Kosovo’s Albanians were trying to get international attention for their cause, and my parents had just come back from a conference on the Balkans in Stockholm. “The European leftists at the conference were terrible!” my 14-year-old self overheard my mother declaring. “How could the leftists be terrible?” I remember thinking.

It wasn’t the only question that was slowly chipping away at the idea of the left having some kind of inherent right to moral high-grounds. Why was it that a few years earlier, a French socialist president called Mitterrand (a name I remember hearing being cursed at home when mentioned in the news) was visibly appeasing and enabling Slobodan Milošević (another so-called socialist) in his clerical-fascist butchery of Yugoslavia? Why was Milošević repeatedly being defended and rationalized as an anti-imperialist figure by global intellectual champions of the left like Noam Chomsky?

How was it possible that the United States, ‘evil capitalism’s’ center of gravity, was championing calls for human rights in the Balkans? Most disillusionment with the left around the world at the time centered on the failure of the Soviet Union, with the argument being that communist regimes didn’t work. Still a young teenager, I was mostly unaware of those discussions, but my worry as I observed the devastation of Bosnia, and my own experience of living under a repressive regime, went the other way: What the hell was wrong with the Western left and its lack of solidarity with the weak and dispossessed?

The more this dissonance grew, and the more I tried to evolve my own ideas, the more I developed a contempt for leftist theory and its armchair intellectuals.

A few years later, the degree of ideological confusion within my 16-year-old leftist self had grown still further. Here I was, fresh out of a war in which ‘imperialist’ NATO had eventually saved my people from genocide, spending a whole day with an artist friend spray-painting graffiti on my bedroom wall with the text ‘Bullet in the Head’ — it was the title of a song by my favorite band, the notoriously anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist Rage Against the Machine, but looking back now, perhaps the bullet was subconsciously targeting my cognitive dissonance.

The more this dissonance grew, and the more I tried to evolve my own ideas, the more I developed a contempt for leftist theory and its armchair intellectuals. There seemed to be something terribly arrogant in the idea that someone sitting thousands of kilometers away, or casting a shadow from hundreds of years ago, could preach morals and schematic formulas for what a fair society should look like, and apply it to contexts they didn’t understand or had never seen. As if human life and morality were things whose variables and complexities could be cracked like the laws of physics.

A better way to connect with the central idea that capitalism rigged the game of life in favor of the rich and privileged seemed to be to read leftist fiction and essays by the more literary intellectuals or human rights activists — those who portrayed the struggle and resistance of people dispossessed by capitalism, imperialism or racism. Jack London’s novels, such as the dystopias of “The Iron Heel,” seemed to bring to life the ways in which unfettered oligarchic rule repressed workers and bred resistance. I will never forget the chills — which I still get to this day — of reading Martin Luther King’s speeches and letters for the first time, particularly pieces like “Letter From a Birmingham Jail,” in which he articulates deep grievances with injustices without ever resorting to hate.

This was the only kind of reading that lit my emotions and made me still feel part of the left, because it connected to other actual human experiences of dispossession, and not to grand abstract theorizing. It also pushed back against another emotional turmoil that was forcing me to question everything about the left — especially the notion of leftism as a family identity. Much of it centered on a teenager’s insecurity and dilemma: Was everything that my grandparents fought for worth it considering how it ended?

I’ve never had any nostalgia about Yugoslavia (which I barely remembered), but it increasingly seemed that, setting aside the undeniable emancipatory elements of the project, its economic and political doctrines were based on plenty of lies and deep internal contradictions and injustices, which eventually imploded.

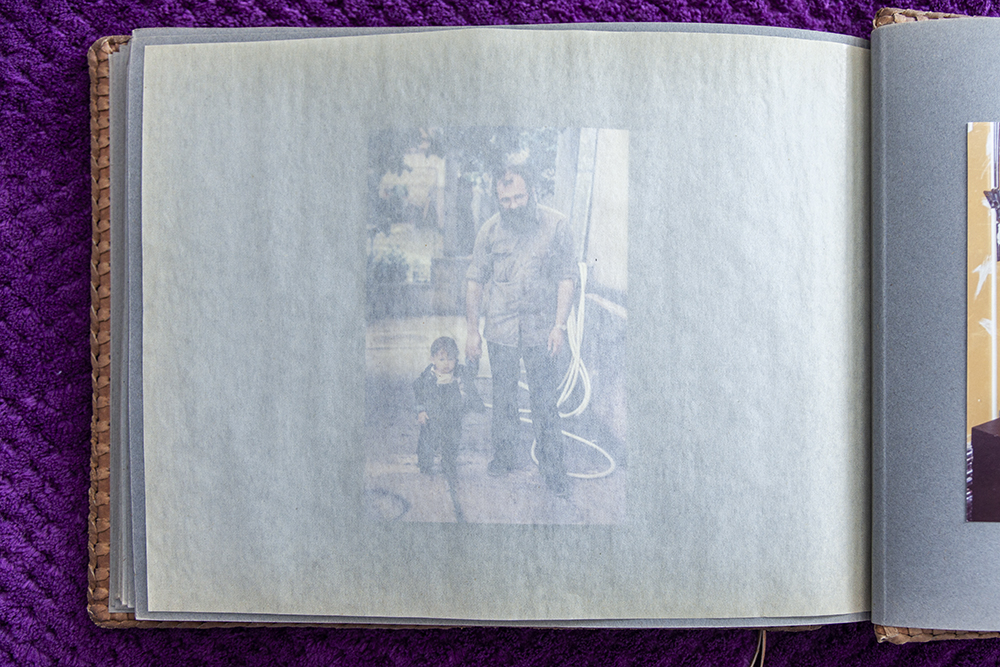

My maternal grandfather Fejzullah was the kindest man one can imagine. A true believer in humanist principles if ever there was one, and as far apart as one can be from national hatred. On April 2, 1999, a Serbian police unit massacred an entire neighborhood in his hometown of Gjakova. It included Fejza’s only brother, Januz Cana, and his entire family. Fejza was so devastated that he was never the same man again. It seemed like the whole world he had helped to build went into those graves with his family members. Mentally and physically weakened, he died a few years later himself.

Then there was grandpa Mehmet’s legacy as a strongman leader in the security sector, having led among other things efforts to establish Kosovo’s Territorial Defense Force. He had reluctantly agreed to a plea by Fadil Hoxha (Kosovo’s highest-ranking leader) to become Interior Secretary in the most difficult of times, tasked to lead Kosovo’s response against the 1981 Albanian student protests. Hundreds were jailed under his command on charges of Albanian nationalism and irredentism.

His generation of Kosovar Albanian communists, loyal to Tito, privately rationalized this violence with the need to defend Kosovo’s almost Republic-level of autonomy from the resurgent nationalism in post-Tito Serbia, which sought to recentralize power in Belgrade and was using the protests as a pretext. But many Albanians then (and especially now) view the actions of Kosovar communists as those of quislings. Whatever the interpretation, no one disputes that it was unjustifiable political repression.

THIS SENSE OF GUILT FROM INHERITED PRIVILEGE REMAINS IN CONSTANT TENSION WITH MY OWN LIVED EXPERIENCE.

Mehmet — a man whose personal integrity, charisma and love for family made him admired at home — passed away in 1985 when I was a mere 1-year-old. But the ghost of his public legacy as a communist strongman lived on, placing a strain on my father’s public engagement in particular, even though he had ideologically rebelled against the regime’s authoritarian nature (and his own father) since the 1960s.

In my professional and public engagements, I have often stumbled upon people of my generation who grew up without a parent because they’d been imprisoned by my grandfather for their political activism. Some now and then remind me of it when they disagree with my writing. I’ve always understood their anger and resentment, and regularly agreed with their argument that transitional justice will not be complete without addressing the crimes of the communist regime.

This sense of guilt from inherited privilege remains in constant tension with my own lived experience of having been a victim of Serbia’s repression along with everyone else. Yet while this tension has been burdensome, it has also been liberating, as it carved the space needed to break loose from the chains of family as a source of ideological identity.

If my grandparents’ generation broke centuries of family tradition by replacing God with Marx, and my parents did the same by shunning the communist dogma of their parents for democracy and human rights, then perhaps the most valuable family inheritance to hold on to was our tradition of self-creation.

The thief called reality

It was around the time when the Iraq war had started in the early 2000s, and I was studying political science and international relations at the American University in Bulgaria, that I remember watching a documentary about the American neoconservatives who had orchestrated the war. The likes of Irving Kristol and other New York intellectuals were talking about how they were all former socialists and Trotskyists who had become conservatives after being “mugged by reality.” I was certainly already starting to feel mugged, but found it incomprehensible how any true leftist could ever become a conservative of any kind.

Still, I recall my idealistic student self being alerted to the possibility that, going ahead, what I considered to be a core set of beliefs attached to my identity might be threatened by this thief called reality. In fact, the latter also became — like all things dangerous and risky — even more tempting to understand. “What was life hiding from me?”

If you think of yourself as a progressive activist — which at the time I certainly did — centering your thinking around reality does not seem very productive; it tames your imagination and sense of agency to drive change. But if you’re also into intellectual pursuits, there’s a tension between the belief in the possibility of human progress, and the instinct not to be gullible in the face of humanity’s tragic capacity for misery.

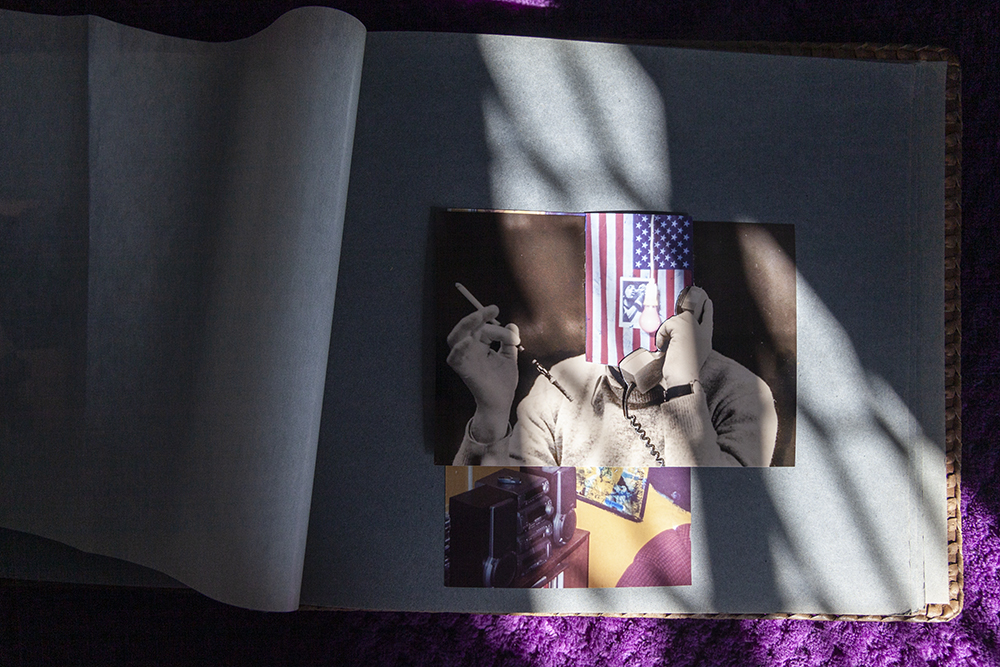

A post-war image constantly on my mind is that of my grandfather Fejza smoking gloomily at his kitchen table, his hands mildly shaking, his head slightly bowed and eyes looking down at the newspaper, unable to cope with the degree of brutality that brought his world upside down when his brother’s family was massacred. The experience of war does a lot of things to you, but in my case the one thing that sticks out is that it made me alert and determined not to be caught as a sucker by inhumanity.

This early disillusionment, coupled with my dual experience of privilege and victimhood, stripped away any romantic or schematic thinking and made me highly suspicious of ideology. It did so by making me acutely aware of the contingency of class status and individual choices, and of how external structural forces shape our moral judgements. Reading Edward Said’s essays and books as a student, I could simultaneously disagree with his excessive criticism of the West and understand why someone from Palestine like him could have a totally different moral outlook on world affairs to mine.

Was it even possible to discuss morals and values as things that are universal and outside of our personal perspectives? Certain principles like those set out in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights seemed morally indisputable as goals, but how could they be practically instructive, considering the political considerations and the multitude of contexts in which people actually live?

These kinds of questions were especially pertinent having as a backdrop the tumultuous post-war reality of Kosovo, where a new middle-class was emerging and a new elite was rising to power. Segments of, mostly rural, Albanian society that had been impoverished during Yugoslavia moved en masse into the cities and public spaces, claiming the spoils of a national liberation war they had bravely led against a genocidal regime, and carrying with them not just an assertive militant attitude, but also century-long resentments against the formerly privileged Serb ethnic minority and colonial rule.

Established urban Albanians like myself were — and still largely are — viewed as somewhat of a permanent quisling class (whether Ottoman or Yugoslav), even though my parents had played an active role in the peaceful independence movement, and my father’s brother (my beloved uncle Gazmend) had fought for the Kosovo Liberation Army.

My skepticism toward ideological thinking grew exponentially as I watched my own displaced urban social milieu, including many of its self-proclaimed leftists, experience this loss of privilege with a kind of hypocritical moral indignation that othered “the barbarous peasants” to the point of dehumanization. Sure, public discourse was all about the predatory nature of the new ruling class. But lurking beneath that grievance I sensed a deep xenophobic zeal and lack of understanding for the historical perspective or the interests of the underdog social classes that the emerging elite represented, and by whom they were voted into power. Such myopic arrogance only caused the disadvantaged to cling to their champions with increasing aggression.

I learned to mistrust moralizing language because experience taught me that it was far too often tainted by insincere and dehumanizing motives.

Many of us ‘urbanites’ failed to see (or did not want to) that what was happening was what usually happens in pre-democratic societies that don’t deal with repressive political orders: Resentments continue their cycle and upward social mobility is possible only at gunpoint. Yet, instead of dealing with the wounds of the past and channeling this social conflict through democratic means, or reaching out to the voter base of the new political class, most chose to further antagonize these identity-based differences.

Sometime in the mid ’00s I remember being impressed by Erich Fromm’s dictum that there is “no phenomenon which contains so much destructive feelings as ‘moral indignation,’ which permits envy or hate to be acted out under the guise of virtue.” I learned to mistrust moralizing language because experience taught me that it was far too often tainted by insincere and dehumanizing motives — driven not so much by a sense of justice and love, but by a rationalized hatred and resentment.

Moral language underpinning any ideology seemed to be a mere instrument of human struggles for dignity and power. Which is why Michel Foucault — whose work explored and dissected how power worked — became the only leftist theorist who seemed to make sense during my late student years. Power, Foucault argued, was constructed by accepted forms of knowledge and truths — which is why elites had the upper hand in shaping it and why, if you want power, you have to target the hegemony of discourse.

In post-war Kosovo, all of this was up for grabs. The experience of apartheid, war and economic deprivation had dealt a decisive blow to notions of brotherhood and unity and the socialist model of economy. The new discursive hegemony was that of national liberation, Western state-building, liberal institutions and market economy. With the exception of the national liberation element, the new hegemony was imposed by the combustion of the old order and by the newly dominant Western forces, rather than reached through bottom-up deliberation. This created the central political tensions of post-war Kosovo.

The only force that grew to contest this new hegemonic paradigm was Vetëvendosje with its initially fringe anti-colonial and leftist nationalist discourse that I always found to be anachronic to the context and ultimately reactionary in results. It seemed to not only be crowding out the already limited space for a leftist critique of post-war Kosovo but through its revolutionary discourse and violent actions that delegitimized elected institutions, it seemed to also have a questionable commitment to my understanding of democracy.

Soft liberal landing

Resistance to grand ideological and moral ideas, and an appreciation for irony, made George Orwell my intellectual guiding light of the ’00s. One of the left’s best known internal critics, Orwell had, through his literature and essays, explored ideology from the perspective of both human potential and fallibility. His most important contribution to the left was perhaps to alert it to the dangers of illusionary thinking.

It seemed that if the post-Cold War left was to be saved from its worst impulses, which produced things like the Soviet Gulag or Albania’s economic misery, and kept presenting mediocre thugs like Venezuela’s Chavez as alternatives to the ‘neoliberal order,’ it would need to find a new language and reject old schematic views of the world. In this new language ‘American imperialism’ was no longer the arch enemy, and words like ‘bourgeois’ were not used every second sentence as a dog whistle to fuel class warfare.

Orwell’s modern-day successors were the likes of Christopher Hitchens, who became my personal hero because he was one of the leftist radicals who got the Balkan Wars right. He did so by deciding not to sit in a chair somewhere like Chomsky, generically blaming American imperialism, but by bothering to go to Sarajevo as it was being mercilessly shelled by a genocidal army. Hitch’s Balkan writing eventually led me to his “Letters to a Young Contrarian,” which offered a blueprint on how to think, rather than what to think, famously warning readers to “beware the irrational, however seductive.”

If you were a young person trying to think about the left in the mid ’00s — the final years of the ‘end of history’ — it was easy to be morally enraged and seduced by reading books like Naomi Klein’s “No Logo” or “Shock Doctrine,” or by following how Western state-building was getting many things wrong in Kosovo. Capitalist markets and liberal institutions had been very disruptive to communities and applied blindly without appreciation to cultural contexts by Western ‘experts’ and ‘consultants,’ exported with almost the same zeal as communist regimes had tried to impose socialist industrialization to peasant societies, and having many dehumanizing results. Kosovo for one felt somewhat displaced with a progressive legal framework that reflected less of what Kosovo’s society stood for, and more of an understanding of rights that Western societies had achieved through centuries of struggles.

Western welfare states, the left’s greatest success stories, had surely shown what was possible.

But it was also hard to ignore that this market-driven globalization and Western diffusion of norms was also bringing hundreds of millions of people out of poverty at a rate unseen in history and building a global middle class. This seemed like something that the left should cherish and build upon, by working to strengthen democratic institutions and social protections, as a means to tackle predatory behavior by elites, rather than returning to its old revolutionary delusions. The response to the new magical thinking of unfettered markets was surely not the old magical, lazy and generic anti-capitalism.

When a Marxist professor at university had introduced Karl Polanyi’s “The Great Transformation” as evidence to suggest that the dominant capitalist culture was a recent construct in the West, one that may be dismantled rather than something representing an inevitable “end of history,” I remember that as a student I had felt relieved by the idea of capitalism’s temporality. But now that I had seen more of the world and was slightly mugged by it, I wondered why capitalism should be dismantled if its productivity could be turned into an asset in reaching social goals. Western welfare states, the left’s greatest success stories, had surely shown what was possible.

I grew particularly (and staunchly) supportive of liberal democracy as a political system, because the opportunity it provided for societies to self-correct and learn from mistakes appealed to my suspicions of human rationality and motivations. These suspicions became amplified once I discovered psychologists like Daniel Kahneman, whose insights on cognitive biases — summarized best in “Thinking Fast and Slow” — are best known for discrediting liberal market economists’ ideas of humans as rational economic actors. But to me, Kahneman’s findings seemed more important in disqualifying humans from any claims of ability to answer any big questions, especially moral ones.

I grew convinced that Isaiah Berlin’s notion of “value pluralism” — which rejected both moral relativism and moral absolutism, acknowledging that there were many conflicting supreme values — was a good balcony from which to view political order. Berlin’s preference for political systems that emphasized negative liberty (“freedom from”) over positive liberty (“freedom to”) created conditions for social progress and experimentation, while shielding societies from abusive predators. A positive understanding of liberty as “freedom to” was far too often abused by groups seeking to arbitrarily impose their certain collective will.

Humanity seemed too vulnerable to its predatory members, so the most important thing was to keep the political field open for the competition of ideas, and to strengthen the democratic institutions preserving this space. Humans were not to be changed as much as their worst impulses kept at bay and their better ones nudged. If the left, which I still believed myself to be a part of, was to achieve any of its goals, it would have to be within the confines of liberal democracy.

Prologue: historical loops

The “end of history” optimism was surely blown out of proportion (although Francis Fukuyama, who is credited with popularizing the term, was himself misunderstood). Within the past decade, capitalism’s excesses have imploded in the West and globalization’s paradoxes (forewarned by the likes of Harvard professor Dani Rodrik) have materialized, deepening inequalities (within countries, but not globally) and ushering in the current era of resurgent authoritarianism, great power competition and devastating impact on the climate — all of which disproportionately affect peripheral regions like the Balkans.

In this context, when you still think of yourself as part of the left, rooting for liberal impersonal institutions, centered on human rights and the rule of law, has often felt like supporting the referee in a football game. Across the board, weaker teams of the dispossessed are still being trampled due to unaddressed structural disadvantages, making them unable to compete in the game. After the global financial crisis, which laid those disadvantages bare, the left was especially reinvigorated in the search for strategies to level the playing fields.

Important battles are being won today in the West, especially in the cultural domain, for example by women who are challenging the discursive hegemony of patriarchy. But in general, the tendency of the left — both in Kosovo and in the world at large — seems to be going toward repeating the same old mistakes of history.

What’s the point of having noble goals when conservatives and reactionaries understand human nature better and beat you in the game of reality?

Instead of redoubling efforts to alleviate structural barriers within the imperfect contours of liberal democracy, today’s left keeps losing those disenfranchised by globalization to the far right; betting on revolutions that never materialize or, when they do, produce rapid disillusionments and governments that are incapable of public policy. Perhaps most worryingly, it keeps feeding a sense of Western self-loathing and demonstrating a weak commitment to democracy.

This is reflected most visibly in the left’s complacency over the threat posed by authoritarian powers like China and Russia, or in the anti-imperialist far left’s outright moral equivalence or even cheerleading for such authoritarian regimes. Everywhere you look, the leftist orchestra is playing variations of the theme of Jeremy Corbyn.

Many authors more qualified than me are struggling to dissect the reasons behind the left’s repeated failures that I will not dare go into in this limited essay. But I have my own favorite culprit — the fact that, while the left is generally credited for secularization, it never really abandoned religious modes of thinking, but wrapped itself around them.

The piousness, self-righteousness and moral zeal of leftists keeps being a useful source of inspiration for activism and the kind of heroism that drove the likes of Sadik Stavileci to their martyrdom in search of a better world. But the delusional thinking it produces also makes it permanently cursed at normal, everyday politics — namely in operating at the level of how humans are, rather than how they should be.

What’s the point of having noble goals when conservatives and reactionaries understand human nature better and beat you in the game of reality?

Almost every day as I take my son to his kindergarten in Tirana — where I now mostly live — I pass by the monument that memorializes the martyrdom of Sadik and his two fellow communist comrades, Vojo Kushi and Xhorxhi Martini. The monument is at the site where they were killed, right off ‘Barricades Road.’

Seeing Sadik’s name inscribed as a daily routine itself feels like a historical loop to those childhood mornings walking down the stairs of my home. I often wonder what an intellectual like Sadik, who spoke six languages, would make of what happened in the decades after he was killed for his beliefs and activism. Most importantly on a personal level, I wonder what he would make of the distinctively social liberal outlook of his distant nephew.

Observing Sadik’s wide smile and projecting within him the kind of sense of humor and irony that is typical of Gjakovars, I often like to believe in the fairytailish mythology that he — much like Orwell as he hung around fellow communist zealots in the Spanish Civil War — was on to something in his skepticism of Hoxha, beyond just a personal disliking.

I also like to believe that there is a common thread, if not a full loyalty to ideas, between how we view social and political struggles in completely different contexts. History, as the saying goes, does not repeat itself, but it does rhyme.

If the realities of capitalism ever permit me to write what I’d actually like to write and less of what I have to, perhaps I could indulge further in this family mythology and write a book of imaginary conversations titled “Conversations With Sadik.” This would surely change nothing in practice except add to the canon of leftist self-help literature.

However, in the introduction I would make sure to note as a caveat Orwell’s piercing and melancholically hopeful observation that progress was nevertheless not an illusion — “It happens, but it is slow and invariably disappointing.”

Feature image: The ‘Heroes of the People’ monument to Sadik Stavileci, Vojo Kushi and Xhorxhi Martini in Tirana.

All original images courtesy of the Maliqi family archive. Designs by Majlinda Hoxha / K2.0.

This story is supported by the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung Gesellschaftsanalyse und politische Bildung e.V. – Office in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

- This story was originally written in Albanian.

Një shkrim shumë i veçantë, një shkrim që të shpie në një botë të thellë mendimesh dhe që të ndihmon në të kuptuarit më real të zhvillimeve politike brenda një shoqërie, të trasnformimit të shoqërive në periudhat pokonfliktuoze dhe për procesin e delegjimimit të trashigimisë post-imperial dhe paralelisht përpejkejev për ndërtimin e një kohezioni kombëtar. Është një ese frymëzues dhe krejt një fund, është një recetë e të kuptuarit edhe të relaitetit kosovar, që nganjëherë prodhon shumë agresivitet edhe për shkak të të qenurit perferi e Evropës.