Djellza Pulatani, a killjoy with intention

The Albanian-American activist giving back to her community.

In-depth

More

Perspectives

More

Longform

More

When the absence of care becomes deadly

How the lack of healthcare in Kosovo fuels suicide and the mental-health crises among transgender people

Videos

More

Recommended

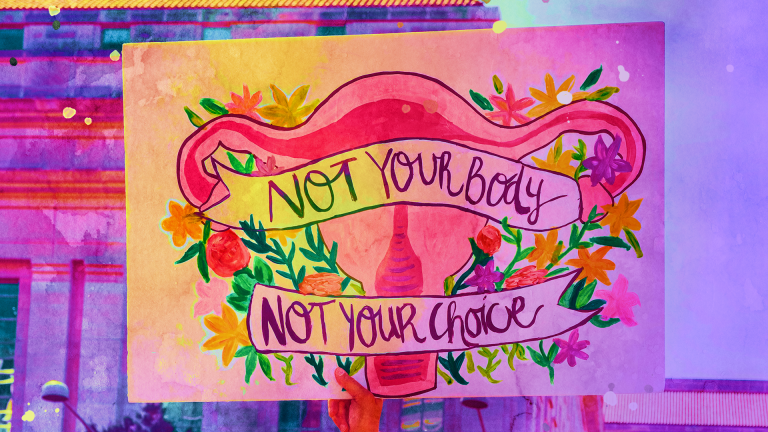

‘Today we march, every day we fight’

In photos: the March 8 call for gender justice.

Podcasts

More

Trending

Pa punë ose pa kontratë

Mustafa thotë se shteti duhet të ndërtojë një dialog më të strukturuar me sektorin privat, i cili mbetet gjeneratori kryesor i zhvillimit ekonomik në vend. Sipas saj, duhet të bëhet një vlerësim i qartë i nevojave të tregut të punës, cilat profile profesionale kërkohen dhe cilat aftësi mungojnë. “Ka një...

Best Bits

Subscribe to Best Bits and receive our best content of the week.

Donate

Help us bring you the journalism you count on. All amounts are appreciated

Photostories

Explore more