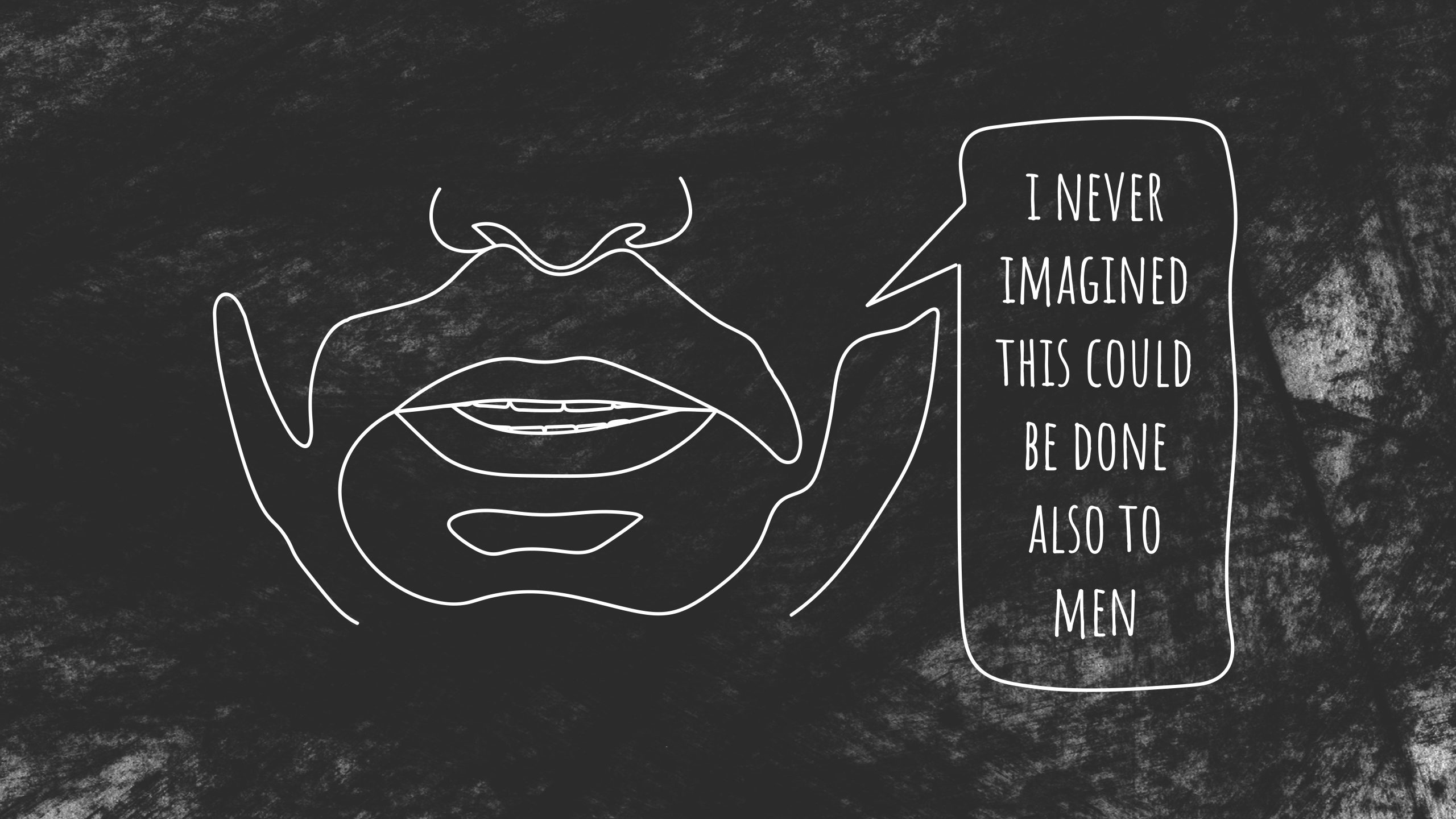

'I never imagined this could be done also to men'

Male survivors of wartime sexual violence seek help after two decades.

|27.10.2022

|

Many male survivors of wartime sexual violence in Kosovo had their genitals damaged and were later unable to become parents.

'Sexual violence against political prisoners was systematic.'

Behxhet Shala'Men find it harder to look you in the eye. Their identity is threatened by feeling emasculated and feminized.'

Selvi IzetiDe Lellio says the narrative of the masculine liberation struggle leaves no room for stories that threaten to feminize men.

Dafina Halili

Dafina Halili is a senior journalist at K2.0, covering mainly human rights and social justice issues. Dafina has a master’s degree in diversity and the media from the University of Westminster in London, U.K..

This story was originally written in English.