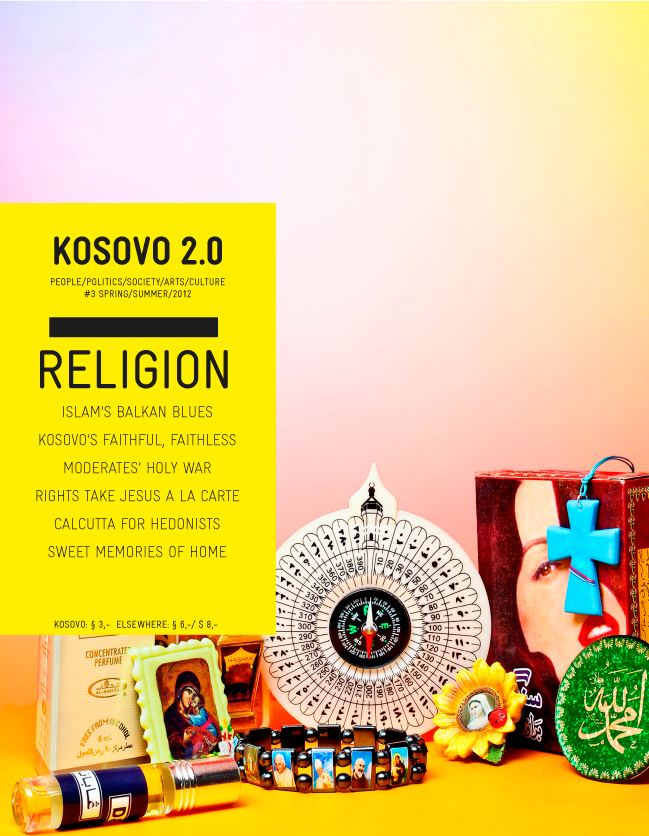

#3 RELIGION

Religion has re-emerged as a powerful force shaping identity, morality, politics and collective life in Kosovo and the broader region. This issue of Kosovo 2.0 gathers stories and analyses — from the rise of moderate religious movements abroad to personal testimonies of conversion or abandonment of faith — to examine how religious identities influence social belonging, public life and contestations over morality, memory and power.

Ultimately, the common thread to our magazine is that religion is not vanishing — whether it’s an entry point to social relations, serves to distance ourselves from it, a reason for oppression or inequality, or a way of evoking memories, people everywhere have stories to share, and they’re using and engaging with different means and instruments to make their calls heard.

Besa Luci

Besa Luci is K2.0’s editor-in-chief and co-founder. Besa has a master’s degree in journalism/magazine writing from the University of Missouri’s School of Journalism in Columbia, U.S..

This story was originally written in English.