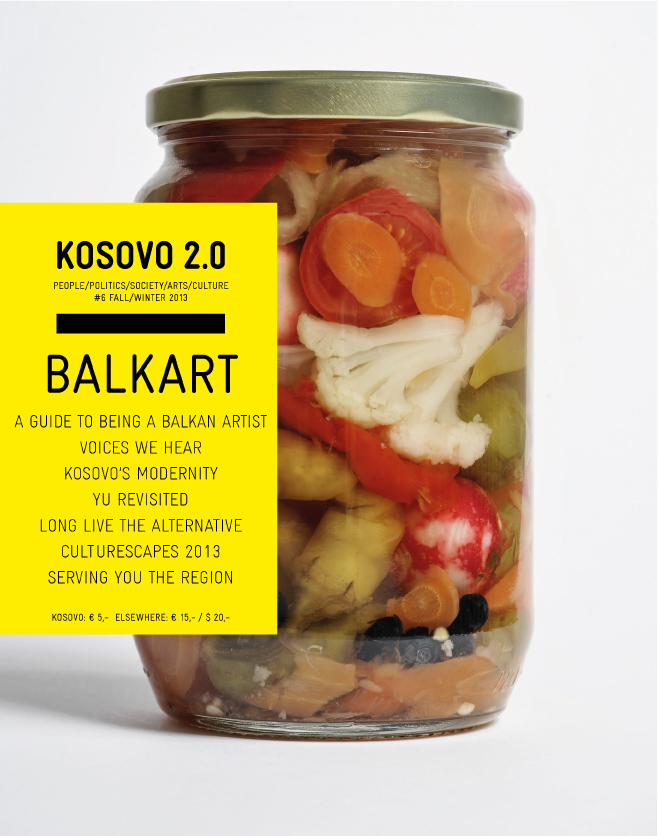

#6 BALKART

“Balkart” centres on art and cultural production in the region, gathering stories from artists — in theatre, film, literature, performance and visual arts — whose work challenges dominant political narratives. It positions art not as peripheral, but as a vital medium through which people reflect on “uncertain transitions,” engage in social critique, and contribute to broader debates about political thought, collective memory and social change in the region.

We challenge the tendencies to locate and define arts from the region as predominantly and exclusively having to be shaped, produced and understood within the constellations of our recent troubled history or our “exotic” present.

Besa Luci

Besa Luci is K2.0’s editor-in-chief and co-founder. Besa has a master’s degree in journalism/magazine writing from the University of Missouri’s School of Journalism in Columbia, U.S..

This story was originally written in English.