“They expect you to find peace over time, but I don’t know… you are so affected,” Isma Begiqi told Kosovo 2.0 in a tone of despair. “Everywhere you go, you feel them behind you… you are always sad. You go out, talk to somebody, but your mind is always with them.” For Begiqi, there will never be closure.

Begiqi’s daughter, Luljeta, was 23 years old when in March 1999 she was taken by Serbian forces. The two of them, alongside other family members, were fleeing their hometown of Mitrovica in the wake of the 1999 NATO military campaign against Serbia. Eight years after the war, in 2007, Luljeta’s body was found in a mass grave in Prizren. Her identity was confirmed based on DNA forensics.

“I always hoped that maybe she ran away and went abroad,” said Begiqi. “There are many stories that people turned out to be alive and I hoped for that. Even today, sometimes I think maybe it is not her body in the grave. Maybe she is abroad.”

Luljeta was given a proper burial in Mitrovica, alongside other Begiqi family graves. However the same does not hold for Begiqi’s husband, who in 1999 decided to stay in their Mitrovica home. Today he is one of around 1,650 missing people in Kosovo.

Torture, killings, rapes, forced expulsions, and other war crimes were committed by Serbian forces against Kosovar Albanians during the 1998-1999 war. International reports and investigations point to a coordinated and systematic campaign to terrorize, kill and expel the ethnic Albanians of Kosovo.

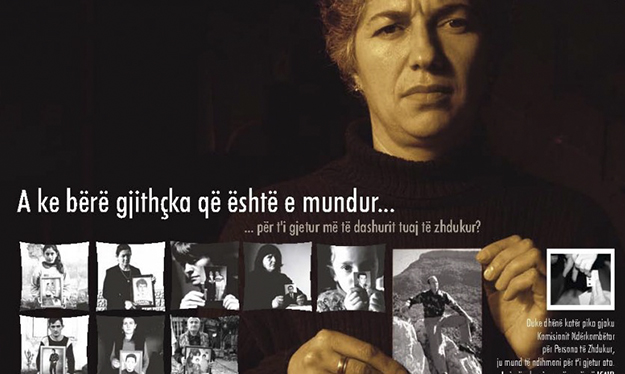

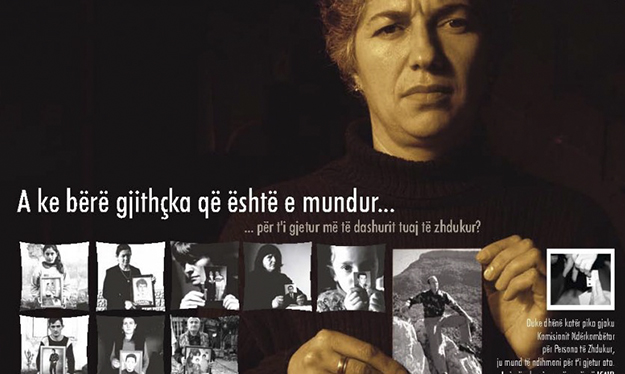

Today, Kosovo marks the International Day of the Disappeared, as across the country families of the victims still await some news on the fate of their loved ones. Families of victims and activists marched today in solidarity and collective remembrance through Mother Theresa square in Prishtina, honoring all of the people who remain missing in Kosovo, as well as around the globe. In a symbolic act, today’s activities ended at 16:50, marking the 1,650 people who disappeared in the country. At the end of the armed conflict it was estimated that there were 5,500-6,000 missing people, although that number has reduced over the years, largely due to the steady uncovering of mass graves.

Statistics show how modern conflicts affect civilians. Before the First World War the ratio of casualties — including those who go missing — was seven combatants to one civilian. Today, the balance has shifted dramatically. The ratio is now one combatant to nine civilians.

In Kosovo, the government Commission on Missing Persons organized a four-day program of activities that began on Thursday (August 27) with a conference. Head of the Commission, Prenke Gjetaj, announced the program for the four-day commemoration activities that traditionally include paying homages to victims at the sites where massacres happened. This year, they visited various sites including the villages of Kralan and Izbica. Eighty six Albanian civilians were killed during the Kralan massacre on April 4, 1999 and 49 of them are still missing. It is estimated that 150 civilians died during the Izbica Massacre on 28 March, 1999.

“August 30 has become our tradition to mark this International Day for the Disappeared, and unfortunately we are also part of this pain,” Gjetaj told Kosovo 2.0. “We still don’t know about the fate of 1,650 persons, and it is our duty, obligation and responsibility to work to shed light on their fate. The families of the victims still live with the hope, longing and sadness for their loved ones.”

During the 1999 war, the bodies of hundreds of Kosovo Albanians were transferred to Serbia by Serb forces, where they were buried in mass graves as a way of hiding evidence of the atrocities. Other unidentified mass graves are believed to exist but ascertaining the disclosure of information relating to their locations remains a serious challenge.

To date, the bodies of almost 900 Kosovo Albanians who were ‘disappeared’ by Serb forces have been exhumed in Serbia. The remains of around 800 bodies were found in mass graves on the Interior Ministry land at Batajnica near Belgrade, and remains of a further 70 were unearthed at Petrovo Selo, a village located in Vojvodina, northern Serbia. The remains of another 84 bodies were found in Lake Perucac in western Serbia. The most recent discovery was the mass grave at the Rudnica quarry near the southern Serbian town of Raska, where 55 body remains were exhumed. Until now Belgrade has failed to prosecute any officials who ordered the criminal operation to hide bodies.

“Eight hundred bodies were found in a mass grave in Batajnica, on the training grounds of a Serbian military unit,” said Bekim Blakaj, executive director of the Humanitarian Law Centre, a human rights-based NGO that supports post-Yugoslav societies in the promotion of the rule of law and acceptance of the legacy of mass human rights violations. “Who could have buried them there without the permission of the leaders and commanders from the highest ranks? No one from Serbia was prosecuted at the [Serbian] special court for war crimes for Batajnica. It is very clear that there is lack of political willingness to shed light on the fate of the 1,650 missing persons.”

The 26-year-old son of Kadri Isufi from Kushtova village in Kosovo was killed by the Serbian military in 1999. “I found my son’s remains five months after the war,” Isufi told Kosovo 2.0. His son was found in North Mitrovica by KFOR troops. “I felt relieved when I learned that my son was killed by a gunshot,” he said. “Older people used to say that the easiest death is the one by the bullet.”

Isufi travels to Prishtina for every national and international day of missing people to participate in the remembrance activities. “They [the government] need to push it [the issue of missing people] forward and I have to be there with other families to march in front of their noses, so that maybe they will remember,” he said.

Sixteen years have passed since the war in Kosovo, but the institutional and political unwillingness continues to prolong the anguish and struggle of the families of the disappeared. When the Kosovo-Serbia dialogue began in 2011 in Brussels, civil society organizations and families of missing people requested that the issue be part of the negotiations. But their hopes were quickly shattered.

“I think that the fate of missing persons must be a topic treated within the dialogue; locating mass graves, as well as the issue of the processing of court cases for war crimes,” said Teuta Hoxha, coordinator from the Youth Initiative for Human Rights. “Unfortunately, we haven’t seen any political willingness from any side until now.”

Blakaj said that there is reluctance to disclose information, particularly from the Serbian side, as it would initiate another process of investigation and prosecution of those involved in the murders, or in hiding the traces; some of whom might still be in power today.

Serbian security forces’ crimes didn’t occur in isolation. There are also alleged abuses by the Kosovo Liberation Army, which is believed to have abducted and murdered civilians during and after the war, including those from minority groups. Despite this, Kosovo is not ready to face the inclusion of minority victims in the public discourse on this topic.

“It is not an honest thing to deny the victims of other communities,” said Blakaj. “There are around 400 Serbs missing and Kosovar authorities need to give their maximum to find out what happened to these people, to find their mortal remains and to learn what happened to them.”

Hoxha thinks that one of the issues that needs to be raised in the public discourse is the fact that Kosovar institutions have a responsibility to shed light on missing persons, and that this responsibility should be carried out without ethnic distinctions. “I have the impression that this issue is perceived as something that needs to be treated only by the international community or by the Serbian side,” said Hoxha. “The public needs to become aware of this [responsibility] and request more accountability from our institutions about the fate of missing persons.”

From 1999 until 2008, UNMIK (United Nations Mission in Kosovo) was the international body responsible for the process of finding missing people. When the EU’s rule of law mission, EULEX, was established in 2008, it took the lead on the issue. Assistance in locating and identifying missing persons has also been provided — first to UNMIK, then to EULEX — by the International Commission on Missing Persons.

Any excavation of a suspected mass or individual grave begins with the order of a prosecutor; until last year, a EULEX prosecutor had to give the order, but now Kosovar prosecutors are able to provide authorization. The prosecutor will only give such an order if there is credible information about a potential site, generally provided by a firsthand witnesses, not through unsubstantiated hearsay.

Issues with Identification

There are around 300 unidentified mortal remains in the Prishtina morgue — 200 men and a little under 100 women — which remain an obstacle to resolving the issue of missing persons.

According to a 2013 report by EULEX’s Department of Forensic Medicine (DFM), when the rule of law mission took over responsibility for investigating missing people from UNMIK in 2008, it became evident that several hundred bodies remained unidentified, almost a decade after the conflict. From the beginning, EULEX came up with some basic assumptions to help direct their enquiries: there were remains as a result of mis-identifications immediately after the conflict; some skeletal body parts belonged to incomplete bodies which were identified and therefore not reported as missing; some remains did not belong to the conflict; and some remains belonged to minorities such as Roma, whose disappearances had gone unreported.

Mis-identifications was an issue that raised a lot of concern among public opinion and particularly among the families of missing persons. In the immediate aftermath of the war, families would generally identify the victims based on their clothes, without the presence of forensic experts.

When DNA testing was later conducted on the remains in mortuaries and on families of missings persons, the picture became blurred and began to cast doubt on some of the previous, informal identifications; this led EULEX to begin exhuming some existing graves over the past few years in order to ensure accuracy in the identification process, thereby trying to provide some closure to families.

According to the DFM’s Tarja Formisto, one of the complicating factors with identification was the fact that Serb forces dug up bodies to rebury them in Serbia; as a result, remains from different bodies were sometimes mixed in one body bag. “Every missing person has a slightly different story and you have to go back and see what had happened and especially how the person went missing, and who had worked with the bones and what has been done,” Formisto told Kosovo 2.0.

Formisto illustrated this with an example from Cabrat, Gjakova. As DFM was working on the morgue’s inventory, they received DNA results from the living relatives of a victim (who was supposedly buried in the cemetery) which they compared with the the DNA from various body parts in the morgue. They received a match. After looking at the information of the victim’s body that was handed over to the family years ago, it was discovered that the same body part was recorded as having been buried in the grave. As a result, they were able to conclude that the body part in the grave, did not belong to the victim at all, and that the remains in the grave were therefore mixed.

With the order of the prosecutor, DFM carried out exhumations in Cabrat Cemetery for further identification and DNA analysis of 14 victims, in order to hand over all of the correctly identified and re-associated remains to their families.

The process of exhumations is not without its difficulties, particularly for the families who often have to go through the uncertainty of receiving the body remains of their loved ones for a second time. There have been suggestions that EULEX has added to this intolerable burden for the families, by carrying out the exhumations in an insensitive manner. Just this week, Kosovo Women’s Network complained to EULEX that recent exhumations in Krushe e Vogel had been carried out under false pretenses, and without appropriate forewarning of family members, thereby causing additional trauma to the victims’ relatives.

Maybe the biggest challenge that Serbian and Kosovar authorities face today with regards to missing people is uncovering information on missing persons whose bodies were potentially destroyed in industrial furnaces, such as those at Surdulica and Trepca.

Blakaj told Kosovo 2.0 that mechanisms for finding the truth through witnesses and documentation are extremely problematic in these cases. “Unfortunately there aren’t undeniable facts, but there are indications that a certain number of corpses were burnt and there is no physical evidence and it is extremely difficult to investigate these cases,” said Blakaj. “Authorities need to do their best to find the witnesses who can testify to the burning and disposal of bodies, because the families of the victims and us, the society, need to know about their fate and come to terms that those mortal remains don’t exist.”

On another marking of the International Day of the Disappeared, 1,650 families of missing persons in Kosovo still don’t know what happened to their children, spouses, parents and relatives, and are still unable to give them a dignified burial, or to mourn at their gravesites. They deserve the closure that the accurate identification of a victim’s body gives them.

Blakaj recalled an event from many years ago when he interviewed a young man from Vushtrri that had just reburied his two brothers that had disappeared during the war and were later found in the Batajnica mass grave. “I can’t remember a time that I was happier than now,” the young man told Blakaj. “It made me think: ‘How can somebody that just buried his brothers be happy?’” said Blakaj. “And at that moment I understood the depth of the pain that families have while their relatives are missing.”K