Ever since the violent measures of Slobodan Milošević’s regime saw him fired from his job three decades ago, working with a cart has not only been a source of livelihood for Sabit Hamiti. It has also been an act of national resistance.

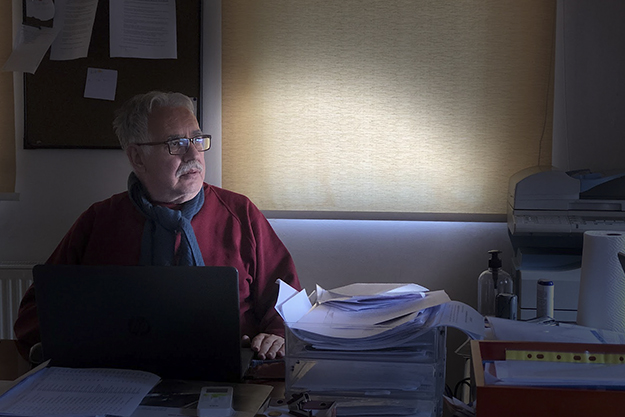

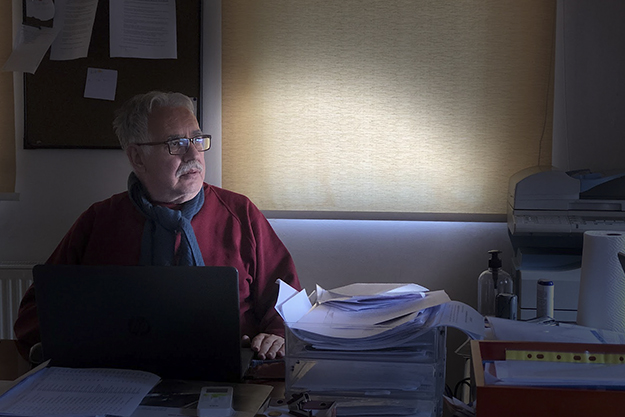

In Mitrovica, he is widely known as “the engineer with a cart.” He was employed at the Construction and Design Bureau of the Trepça combine’s Lead and Zinc Institute. After he was left jobless, he was not only responsible for his family of four, but also for his mother and brother.

His father’s last wish was for him not to leave his home country under any circumstance, so he says that, with his example, he wanted to show that even backbreaking work should not serve as a reason for anyone to leave their country.

Like Islami, Meleqe Mehmeti-Buzhala — who worked at the Directorate of the “Gërmia” department store in Prishtina — was also removed from her workplace in 1990 by the Serbian administrators of the enterprise, saying that she was a “technological redundancy.”

Not until after the end of the war in 1999, did she set foot in the now protected building located in the city center. She says that, for a long time, she felt like crying every time she passed by the building. “It’s not a matter of hatred, but I will never forgive them. They have made us grow old before our time,” she says, referring to the Serbian regime of the time.

Stories like these, with more or less drama involved, can be heard from the nearly 150,000 people who were expelled from their jobs because they refused to submit to the violent system installed by Milošević at the beginning of the ’90s. Their economic potential went down the drain, to their personal detriment and that of the Kosovo economy in general.

Economics experts have estimated the material damages to be in the billions, but Kosovo has not managed to discuss this issue with Serbia. Besides economic losses, the social and psychological trauma inflicted upon entire generations remains immeasurable.

If that was not enough, Kosovo staged the second act of trampling on these citizens. To receive a full contributory pension of over 200 euros, a worker must have paid contributions for no less than 15 years before the war. In other words, for example, 14 years and 364 days are equal to zero days, and they are thus demoted to a basic pension of under 100 euros.

Working to patch up their livelihood

Islami is one of those citizens who are not entitled to a full contributory pension, despite also working before the war.

His first job was in hydro engineering in Vojvodina, Serbia, while he was employed at the Trepça Combine in 1981. “I was part of over 150 different projects, laboratories, scientific papers, various sketches only dealing with construction,” he recalls, taking a sip from his coffee cup at one of the restaurants on the banks of the Ibër River in Gushac, Mitrovica.

“At the time, half of the employees at the Institute were Albanian, and the other half Serbian,” he further explains, adding that he was one of the first Albanians who was employed in this bureau. During the almost 10 years he worked there, he says that he had a good rapport with his co-workers, until the year 1990 when he was discharged and did not show up there anymore.

“At that point, I told myself that I would do manual labor, and I would not submit to the Serbian regime or to migration."

Sabit Islami, engineer

“I was suspended on March 11, 1990,” he recalls. They told me to go work in Kishnica, Novobërdë — to take somebody else’s place. I, of course, did not accept, because that meant accepting Serbia’s program.”

He did not have any second thoughts at the time. He was blunt, and he does not regret the decision he made three decades ago this year. “There was a nationalistic feeling — how could I agree to a program that most Albnians refused?”

Islami decided to turn to the court, but he says that the process dragged on for two years and the final decision was not in his favor — his contract was terminated. “In the court of first instance, the director of the violent measures did not show up at all, but in the second instance, he was forced to. He didn’t even know me. The judge asked him, “How did you sign the decision to discharge him without knowing him?” Islami remembers, chuckling ironically.

He remains convinced about one thing: The system aimed to remove Albanians not only from their workplace, but also from Kosovo. According to him, Albanians at the time had no other choice but to emigrate.

“At that point, I told myself that I would do manual labor, and I would not submit to [the Serbian regime] or to [migration]. I would not take my children through Romania or Bulgaria,” he recalls thinking.

He would remember a conversation from a long time before with people who collected recyclable scrap metal to sell in Zveçan, asking them how much they earned working with carts.

“They told me, ‘As much as you earn at the Institute.’ I told [myself]: ‘Why would I not work?’ I got a cart and started working,” he remembers. “I also did it to convince them [the Albanian colleagues] that it’s no shame, but rather [an act of] national resistance.”

Islami learned to love the work he did, so he arranged his schedule from the outset: “I will not be lying down when the sun comes out, and when it sets I’ll stop working.”

Sabit Islami starts his workday on the banks of the Ibër River, where he sits for a while on a boulder that he painted himself. Photo: Artan Krasniqi.

His routine has remained unchanged. At 5 a.m., he sits on one of the large boulders on the riverbank in Gushac, which he has painted white; he says that everybody knows only he sits there. He stays there until 7 a.m., enjoying the fresh air. Then, he drinks his morning coffee and moves on to the bazaar, walking an average of 20 kilometers per day.

Like Islami in the past, Mehmeti-Buzhala also began feeling accomplished when she started earning her own salary. At the time she was already married, working with her now late husband at the former “Gërmia.”

She was a typist at the enterprise’s directorate. She got her job in 1976, two years after Kosovo gained autonomy within the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY), when some positive changes were ushered in, especially in education and employment.

According to her, life was good at the time even with only one salary per home, let alone with two. “Those years were good for workers, the conditions were better. Until 1981, the rapport between co-workers was very good,” she remembers.

That year, the anger of Albanian students manifested as demonstrations in favor of better conditions at the university canteen in Prishtina, and continued as popular protests. It signalled an ideo-political differentiation that was noticeable not only in Kosovo, but in the whole of SFRY.

In Kosovo, which at the time was an autonomous province of Serbia within the federation, the Albanian majority demanded equal status as a republic. Meanwhile, the crisis would unfold in the whole of the federation, where political reshufflings were based on nationalist agendas that would lead to the destruction of the socialist system.

The tensions would also reflect on the rapport between Albanian and Serb co-workers in Kosovo. When remembering the ’80s, Mehmeti-Buzhala speaks about a deterioration of relations between her and her Serb colleagues to the point of arguments occasionally turning physical.

Sociologist Anton Berishaj remembers how the widespread pressure at the workplace and elsewhere during those years reached a tipping point with the suspension of Kosovo’s autonomy in 1989 and with the “deinstitutionalization of the Albanian population.” “It might have seemed like an unbelievable situation, but it happened,” says Berisha, adding that it came as a surprise to many people.

Palokë Berishaj, who at the time led the Union of Independent Trade Unions of Kosovo (BSPK), remembers aspects of the socio-political context that preceded the decisions or mass expulsion of Albanians from the workplace.

“When Kosovo’s autonomy was stripped, one of the most important decisions was the seizure of leadership positions in all state institutions, as well as in public and social enterprises,” he says. “All of those positions would be filled by Serbs, while Albanians were left to come to terms with this fact.

“Most of [our] Serb colleagues were in solidarity with Serbia’s decisions: ‘Moraju se poštovati odluke države Srbije [The decisions of the Serbian state must be respected],’” Berishaj remembers.

He remembers that Kosovar Albanians back then had one goal: “To prove that Milošević would not find Albanians at any level that accepted his discriminatory policies,” and adds that to this end, “the solidarization and interaction of all workers turned into an existential issue.”

Berishaj also remembers the political organizing in Kosovo that surged in 1990. “It resulted in the announcement of the [Constitutional] Declaration on July 2, the approval of the Constitution on September 2, and then the independence referendum,” he says, summarizing the developments that guided the peaceful resistance of Kosovar Albanians during that decade, while they dealt with the systematic discrimination and police violence from the Serbian state.

In 1990, Mehmeti-Buzhala was on maternity leave after giving birth to her daughter. The mass expulsion of her Albanian colleagues from the workplace had started — she knew very well what was awaiting her.

“When my maternity leave was over, I went to claim my annual leave. They told me that there was no leave [for me] and categorized me as a technological redundancy,” she remembers. “They sent us to the Agency for Incorporation [an agency similar to today’s Employment Agency] allegedly until they found other jobs for us. It was like that until 1993, when they finally decided to discharge me.”

“At one point, both of us were jobless. We had four children."

Meleqe Mehmeti-Buzhala, typist

She keeps a copy of the decision in her folder — a red book that encapsulates her unfinished career. The document is obviously a template where only the name of the employee and the date of termination were left blank. The reason why “she became unnecessary” for work was the same as for many workers. It hid behind the term “technological advancement.”

“Even if they’d let me return I wouldn’t, everything was ruined,” Mehmeti-Buzhala says.

Her husband also shared the same fate, previously working in the home appliances sector within the same enterprise. “At one point, both of us were jobless. We had four children. He was unable to find something else, so he mostly stayed at home,” Mehmeti-Buzhala says, with a changed tone of voice after having to remember their struggle for survival.

“My father was a tailor, so I started sewing — that’s how I supported my family,” she says, recalling that once again getting used to the craft taught to her by her father was not easy at all. “I earned enough to survive, so that I wouldn’t have to borrow from anyone. Until 1996 or 1997 we had business, but when the war started people did not need to sew things — people didn’t have money, they saved up because the future was uncertain.”

It has been a while since Meleqe Mehmeti-Buzhala stopped sewing, but she still keeps a sewing machine as a valuable artefact. Photo: Artan Krasniqi.

Prematurely mature children

Naturally, it was impossible for the crisis not to have an effect on the children of the ’90s. There are countless cases where children were forced to work in order to help their families through the economic crisis. In the end, all Kosovars fought the same battle: for survival.

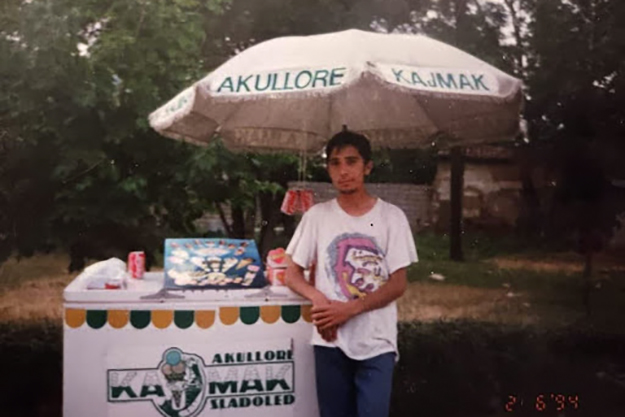

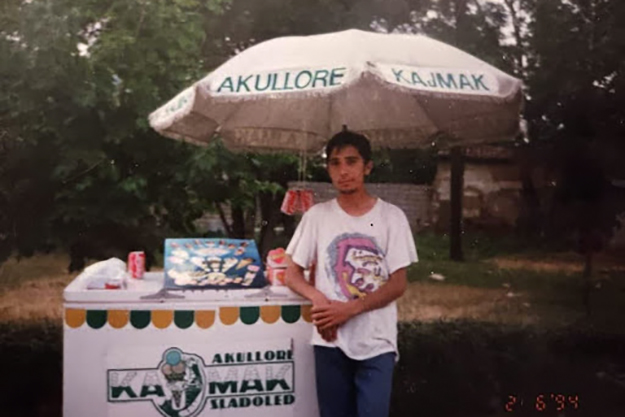

Rilind Gërvalla was a teenager at the time. As a youngster who was passionate about rock music, his free time was completely occupied by the necessity of work. His experience at the time, as someone who had just entered high school, is as motivating as it is sad.

“It was July 1990 — I was happy that I had enrolled at the prestigious ‘Xhevdet Doda’ school,” he says, recalling that summer.

“My now late father worked in the finance [department] at the Radio Television of Prishtina; he came back [from work] at about 6 p.m., all sweaty and very emotionally troubled,” says Gërvalla, now a middle-aged man, remembering the day when his father was left jobless. “He hugged me tight and said ‘every bad thing brings something good along with it,’ and cried.”

He adds that it did not take long for his mother, an English language teacher, to also be removed from her school. The regime’s strike against the education system was a history in and of itself. High school and university buildings were closed to Albanians at the beginning of that decade, and after a few months of mobilization, lessons continued as part of the parallel Albanian education system, which was held in the private homes of volunteers.

“She and other teachers continued working for two years without a salary. We were four children, my three younger sisters and I with two unemployed parents,” he says. “The people started staging actions of solidarity, especially the diaspora, and helped us to at least feed ourselves.”

Sociologist Anton Berishaj also speaks about increased solidarity in response to the violent regime.

“A new Albanian social reality was created — besides activism and traditional social mechanisms for overcoming conflicts, like the Action for Blood Feud Reconciliation, the feeling of closeness between people of one ethnicity began increasing, and it went beyond the usual familial connection,” he says. “The challenge of resisting on a national basis and of activating the dormant historical potential increased, especially in the comunist period that aimed to marginalize national instruments in favor of creating the ideological values of brotherhood and unity.”

Against this backdrop, starting high school was a grim experience for Gërvalla.

“They removed us from school in the first semester, my class continued taking lessons at my house because it was safer,” he remembers. “My father initially began working for the Union of the Radio Television of Prishtina, then when it was abolished after the establishment of the government in exile, he continued in the Kosovo Financial Committee, and my mother worked in the parallel education system.”

Kosovo’s government-in-exile had already been established at that point, functioning with the Three-Percent Fund, collected from contributions from Kosovar and diaspora citizens. According to the unionist Palokë Berishaj, expelled workers became the backbone of the political movement.

Trade Unionist Palokë Berisha remembers the unionization at the time which he says was unbreakable. Photo: Artan Krasniqi.

“In addition to the Three-Percent Fund, there were also solidarity funds set up by organizations that helped workers who were removed from their workplace,” Berishaj remembers. “[The expelled workers] would participate in demonstrations and support education, they were activists and political leaders.”

In order to oppose Serbia’s violent measures, the violent expulsion of workers, the replacement of Albanian staff with Serbs and the violence that was being committed all over Kosovo, the BSPK decided to declare a general strike on September 3, 1990.

Remembering that fateful day, Berishaj says that the whole of Kosovo was quiet: No activity, no loud voices — just unprecedented silence and solidarity.

“It was, in essence, a general and absolute referendum of Kosovo Albanians: A big ‘no’ to Milošević and his policies,” he says. “Naturally, we also understood the risks of this action: Serbia exploited the solidarity of the workers participating in the general strike and began the massive and violent removal [of workers] from their workplaces, breaching every international convention on labor union organization.”

In 1953, the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia had ratified the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, and in 1987 it had also ratified the European Convention for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment.

“It wasn’t easy at all to stay in Kosovo when most left."

Rilind Gërvalla

Gërvalla, then a high schooler, remembers that at the beginning of the ’90s he would go to school in the morning. In the afternoon he would occasionally work at his friend’s company, installing kitchens and moving furniture.

“The salaries that my parents earned were only enough for food and notebooks for us children,” he says. “We would borrow the books. I bought used clothes, shoes and coats at the flea market until I was a high school senior.”

When he graduated from school in 1994, he remembers his friends getting him a job as an ice cream vendor. He had already started working by the time he had to go to prom.

“I borrowed the clothes from a friend who went to a different high school, I locked the ice cream freezer with chains and got dressed at a boutique in town,” he recalls. “I washed my hair with cold water and hand soap, a bit of gel so that the girls would notice me, and we walked to the prom…”

Rilind Gërvalla, who was a high schooler at the beginning of the ’90s, says: “Sometimes, large scale terror can be a stimulus to create songs and poetry.” Foto: Artan Krasniqi.

When he thinks about that time from today’s perspective, he says that his generation was politically mature and understood that it was “part of a resistance for liberation and independence from Serbian oppression.”

“Although those years were traumatic, I proudly remember the resistance of my friends, the engagement, the illegal activity of my family,” Gërvalla says. “It wasn’t easy at all to stay in Kosovo when most left.”

Legally supported discrimination

In order to cause all of this trauma, the Serbian state, among others, had to make a lot of legislative changes.

After the revocation of Kosovo’s autonomy in 1989, the Popular Assembly of Serbia issued two separate laws: The Law on the Operation of Republican Bodies in Special Conditions and the Law on Employment Contracts in Specific Conditions.

An October 2019 study by the Research Institute of Development and European Affairs says that the first law was used to end the constitutional order of the former Yugoslavia and to strip Kosovo of its autonomy, whereas the second law — which was applicable only in Kosovo — served as a basis for instituting the temporary, violent measures.

The late lawyer Nekibe Kelmendi compiled a 200-page document with the discriminatory changes in legislation that were pushed by Slobodan Milošević’s regime as early as 1994. For every alteration in the legislative system, Kelmendi gave a professional comment. One of the documents cited there was “The program for establishing peace, freedom, equality, democracy and prosperity in the Autonomous Region of Kosovo,” published in the Official Gazette of Serbia on March 30, 1990. In fact, this program brought anything but peace and democracy.

As Kelmendi noted, a paragraph of this program foresaw “the dynamics of the settlement of citizens in Kosovo,” which, it says, “will be harmonized with the dynamics of filling new jobs in factories and newly opened enterprises and the dynamics of construction of apartments.”

“All the necessary conditions will be provided so that from mid-June 1990, the arrival in Kosovo of the first group of interested citizens is organized,” Kelmendi said at the time about the program.

It was a new phase of colonization of Kosovo by Serbia. Kelmendi analyzed that “special commissions were formed in all of Kosovo’s municipalities that initially dealt with the employment of Serbs and Montenegrins in organizations, institutions and governing bodies throughout Kosovo, as well as providing living conditions for Serbs and Montenegrins who would come to live and work in Kosovo.”

This period, when most Albanian workers were being dismissed from their jobs and replaced by others, also had severe psychological consequences.

However, beyond the unpaid wages due to dismissal, the question is whether the loss of social potential can be quantified.

Njomza Llullaku, psychologist and professor in the Department of Social Work at the University of Prishtina, says that longitudinal studies — observational studies conducted over long periods of time — show that unemployment has a significant effect on mental health. “Those who are unemployed report higher levels of depression, anxiety and lower self-esteem,” Llullaku says.

According to her, the decision to expel most Albanians from their workplaces in the early 1990s was a manifestation of a genuine rejection of Albanians as citizens of Yugoslavia, as well as from the supposed idea of Yugoslavia.

“Given that the negative effects of unemployment were already known in the early 1990s, the expulsion of the majority of Albanians was a loud and clear indication of a regime that only had bad intentions for the local population,” Llullaku says.

She therefore categorizes it as “an idiotic decision from a human right’s perspective, but one that accelerated the destruction of the Yugoslav state by showing other members of the federation that their independence could be jeopardized by the whims of Serbia.”

“Eventually, from a psychological perspective, this continued hardship forced people to take a stand and fight for their rights as if their lives depended on it,” Lullaku says.

According to psychologist Njomza Llullaku, the difficult living conditions as a result of discriminatory policies by the Serbian state forced Albanians to create “stronger networks of resistance inside and outside the country.” Photo: Artan Krasniqi.

The lost billions

Beyond the ethnic-based discrimination supported by legal changes, Kosovo made a calculation of the economic damage caused by Serbia during the ’90s.

A document that summarizes the damage in numbers was compiled in 2005 by the Unity Team led by President Ibrahim Rugova, which included all leading politicians of the country. The aim of this team was to represent Kosovo in the “Vienna Negotiations for the Final Status of Kosovo” between Kosovo and Serbia, with the international mediation of Marti Ahtisaari, who was preparing the “package” that would pave the way for the independence of Kosovo in 2008.

Economics professor Muhamet Mustafa was chosen to lead the group of experts in this field, and in his book “Overcoming Loneliness,” he describes the group’s work in detail. In one part, he explains how they calculated the economic damage by using the statistical data of the average salary in Kosovo and the number of people dismissed, which he says gives an accurate assessment of the national-level economic picture.

Mustafa says that the Vienna documents, drafted by experts under him, state that “administrative and violently-imposed bodies in socially-owned enterprises and other institutions in Kosovo from 1990 onward discriminated against and illegally excluded from work about 146,000 workers.”

Mustafa points out that “calculated on the basis of the average wage, the lost wages of these workers reach about 4.9 billion U.S. dollars, respectively about 5.4 billion U.S. dollars with a capitalization of about 2% per year.”

However, beyond the unpaid wages due to dismissal, the question is whether the loss of social potential can be quantified; as well as the benefit that society would have from the work performance of these 146,000 people — if they had been left to work at their jobs.

The economics professor says that such a thing can be calculated through certain statistical models, or indirectly with the effects that this had on the decline in gross domestic product (GDP) in Kosovo during those years. “According to some statistical estimates, this amounts to around 11 billion dollars,” he says.

The expulsion has resulted in the loss of pension insurance contributions and other benefits, such as child allowances.

Meanwhile, economic expert Sokol Havolli, currently Deputy Governor at the Central Bank of Kosovo, says that it is not easy to make an adequate assessment of the economic developments of the ’90s. According to him, in the 1980s the highest level of GDP per capita was comparable to about 1,700 euros per year.

“This level, during the ’90s suffered a drastic decline to a level comparable to 500 euros per year”, Havolli says. “While in 1998-99, GDP per capita decreased to about 250 euros per year. So, the economy was completely destroyed.”

At the individual level, Mustafa emphasizes that naturally people would have had ambitions for promotion at work, which usually translates into an increase in salary. “So, [it is] a serious damage to the structure and quality of human and intellectual capital, which is essential for the development of a country,” he says.

Furthermore, he explains that the expulsion has resulted in the loss of pension insurance contributions and other benefits, such as child allowances.

The former trade unionist Palokë Berishaj says that at that time, his generation was at the peak of its physical and mental capacities — eager for work and full of enthusiasm. “Obviously, 10 years out of work, out of the profession, is irreparable damage,” he says.

Ineffectual dialogue

From a political perspective, the Kosovar side has been negligent, according to Mustafa, who was also a member of the Assembly of Kosovo from 2014 to 2017. He says this topic has not been dealt with in the political confrontation with Serbia.

“Although these aspects have been studied and presented to the international community in the context of the talks in Vienna (2006-07) on the status of Kosovo, I think we have not been systematic and responsible enough to continuously keep open and present these and other general aspects of the apartheid installed by the Milošević regime,” Mustafa says.

On these topics, in relation to Serbia, he believes that Kosovo has been in a defensive position, which he deems unforgivable.

In fact, in March 2011, the Government of Kosovo drafted a Platform for interstate technical dialogue between the Republic of Kosovo and the Republic of Serbia. At the time, Edita Tahiri — leader of the Democratic Alternative of Kosovo party that was then part of the Democratic Party of Kosovo-led government — led the technical dialogue in the EU-facilitated negotiations in Brussels. Later, when the dialogue had long moved from only technical discussions to include political dialogue, she took part as minister for dialogue and deputy prime minister.

In the third chapter of the Platform, which discusses the dialogue agenda, a list of “issues and problems created in the war and post-war periods” has been compiled. It states that the list is not exhaustive, while the eighth point is about “compensation for war damages by Serbia.”

In March 2014, almost a year after the April 2013 signing of the “Brussels Agreement” on the principles of normalization of relations between Kosovo and Serbia, the office of Deputy Prime Minister Edita Tahiri drafted another document that highlighted the topics that Kosovo had an interest in opening in the EU facilitated dialogue. The fourth point was on “war reparations.”

“In the case of war damages in Kosovo caused by Serbia, regarding reparations as a part of international law, the state of Kosovo as an injured party must seek reparations [in the form of] compensation, guarantees and justice,” the document says.

Kosovo, based on this document, expects that compensation, among other things, includes “physical and moral damage to the state and individuals; pain, suffering and emotional suffering; damage of missed opportunities including education; material damage and damage to potential lost gains; damage to dignity and reputation.”

One of the points mentioned is that of “compensation for salary losses of persons fired from work due to nationality.” Also, based on this document, the Brussels dialogue aimed to raise the topic of “compensation for the destruction of the pension system.”

The Platform drafted in 2011 also mentions another issue related to this, that of “returning the pension fund for the citizens of Kosovo.”

The state of Kosovo has rubbed salt into the wound of today's pensioners, the same ones whom the Serbian regime fired en masse in the past.

Regarding the pension fund, Adil Fetahu — who led the group dealing with the issue of dismissals and unpaid salaries when the Unity Team was founded in 2005 — provided ample arguments in his 2015 article titled In Defense of the Rights of Pensioners, as well as his 2019 study titled The Issue of the Kosovo Pension and Disability Insurance Fund in the context of the ultimate ‘Grand Finale’ between Kosovo and Serbia.

“In addition to the assessment of monetary damages arising from the termination and misappropriation of [the pension fund], as well as the suspension of pension payments to contributing pensioners by Serbia, there is also a need to assess non-monetary damages and other related costs,” the study says.

In response to criticism for the persistent non-involvement of these issues in the political confrontations with Serbia, the Kosovar side has consistently used the reasoning that in the dialogue facilitated by the European Union it can not impose its own topics.

The second act of discrimination

It has been 12 years since Kosovo declared independence and there continues to be a different type of discrimination against generations. So, in addition to the failure in relation to Serbia, at the domestic level, the state of Kosovo has rubbed salt into the wound of today’s pensioners, the same ones whom the Serbian regime fired en masse in the past.

There was no pension system in Kosovo from the end of 1998 to 2001. As of December 2001, the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK) issued Regulation 2001/35 on pensions, based on which it regulated the basic pension and pensions based on individual savings. And there, it did not recognize pre-war contributions.

A few years later, in 2007, the Ministry of Labor and Social Welfare in the government of the time issued Administrative Instruction number 11/2007 for the implementation of Decision number 13/277 of the Government of Kosovo, which aimed to increase the amount of pensions. Until then, the monthly pension amount was only 40 euros, and it would become 75 euros from 2008. But, this increase would benefit only those who managed to prove 15 years of work experience before the war, thus making the initial division between the contributory pension and the basic one.

Another Administrative Instruction issued one year after the declaration of independence, in 2009, aimed to implement a government decision taken in the same year, which increased the basic pension and that of contributors from 5 euros, to 45 and 80 euros respectively.

These guidelines were rejected in 2014, when the Assembly of Kosovo issued the Law on State-Funded Pension Schemes, which categorized pension beneficiaries. Among other things, there is the “basic old age pension,” as a regular monthly pension paid to all citizens of Kosovo who have reached the age of 65, regardless of whether they were employed or not. It also includes the “old age contributory pension” for those who paid contributions to the former Kosovo Pension Fund before January 1, 1999, according to the provisions of the Law on Kosovo Pension Funds.

The Administrative Instruction that supports the Law on Pension Schemes, when defining the conditions that must be met to obtain the status of a contributing pensioner, states that there must be a “contributory pension experience of at least fifteen years before 01.01.1999.” This must be proven by about 20 documents, the provision of which requires paying visits to many offices and institutions.

Not only that, but if someone who turns 65 today left their job in 1990, they would have been aged 30 at the time. So they would have had to have started working as a 15-year-old in order to achieve 15 years of work experience.

Currently in Kosovo there are 23 pension schemes regulated by eight different laws, which often contradict each other.

While work experience for workers in healthcare and education, and for others who were employed in the parallel system of occupied Kosovo between 1989-99, is recognized, other pensioners need to come to terms with the basic pension, which is less than 100 euros.

In a parliamentary debate on the rights of contributory pensioners held in August this year, the minister of labor and social welfare, Skënder Reçica, promised that a solution would be found, describing Kosovo’s current pension system as a kind of “legal chaos” where “great discrepancies” can be found.

He promised that with a new draft law “the work experience of all employees who were forcefully fired between 1990 and 1999 will be recognized and on this occasion the right to a contributory pension will be recognized for these ’90s workers.” He also said that the bylaws for the recognition of diplomas of all pensioners who graduated between 1991 and 1998 will be changed.

Currently in Kosovo there are 23 pension schemes regulated by eight different laws, which, as the minister himself admitted before deputies, often contradict each other.

Today, the “engineer with a cart” Sabit Islami, in addition to the roughly 150 euros that he earns working with his cart, also receives an early pension. “If I were in my workplace today, besides earning a salary of about 800 euros, I would also have 35 years of experience,” he says, calculating that his hypothetical pension would be at least 400 euros.

Forever disciplined when it comes to work, Sabit Islami says that there have been times when he has worked 365 days in a row, “uninterrupted.” Photo: Artan Krasniqi.

In the 21 years after the war he has not gone to North Mitrovica with his cart. “I wouldn’t want my colleagues to see me and say how the Albanians have left me, ‘They haven’t found him a job,’” he says angrily.

The other worker fired in 1990, typist Meleqe Mehmeti-Buzhala, still vividly feels the mess she says was caused by UNMIK staff on one day in 1999 after the war when they decided to take over the building of the former Gërmia in the heart of Prishtina. Prior to that, she said all Albanian employees had returned there, and with their own investment were aiming to bring back the glory to the company where they had worked for years.

“We elected a director, the number of registered workers went up to 480, but they had nothing to do,” she says. “When we went in that morning, we saw [the mess]; I do not understand why the doors were broken. We started a sort of protest against UNMIK, the police came out and blinded us. We went to the Customs warehouse, turned them into offices and started working there until some time in 2007,” she recalls.

“The discrimination continues further,” she says, now retired, adding that she needed a lot of effort to prove that she had 15 years of work experience from before the 1999 war in Kosovo.

Muhamet Mustafa says that politicians remember the situation of these pensioners only during elections.

“It is true that direct reparations should be sought from the culprit, the government of Serbia, which will certainly be put on the table in Brussels,” he says. But a large number of [workers] are left with low pensions, and after the liberation if it were not for solidarity from their family their level of existence would also be at stake.”

Gërvalla, on the other hand, asks the question: “Isn’t it a shame?”

He answers it himself.

“My father, for example, died without working for even one day in a state job after the war, despite applying,” he says. “Ironically he retired during the days when the country became independent in 2008. How did these contributors spend their retirement, these patriots who helped with liberation, resistance and independence? With hospitals in a critical condition, without care and without the support of the state. Simply said, they did not deserve this present.”K

Feature image courtesy of Sabit Islami’s personal archive.

This publication is part of the third cycle of the Human Rights Journalism Fellowship Program, supported by the European Union Office in Kosovo. The program is co-supported by the National Endowment for Democracy. This program is being implemented by Kosovo 2.0, in partnership with Kosovar Center for Gender Studies (KCGS), and Center for Equality and Liberty (CEL). Its contents are the sole responsibility of Kosovo 2.0 and do not necessarily reflect the views of the donors.