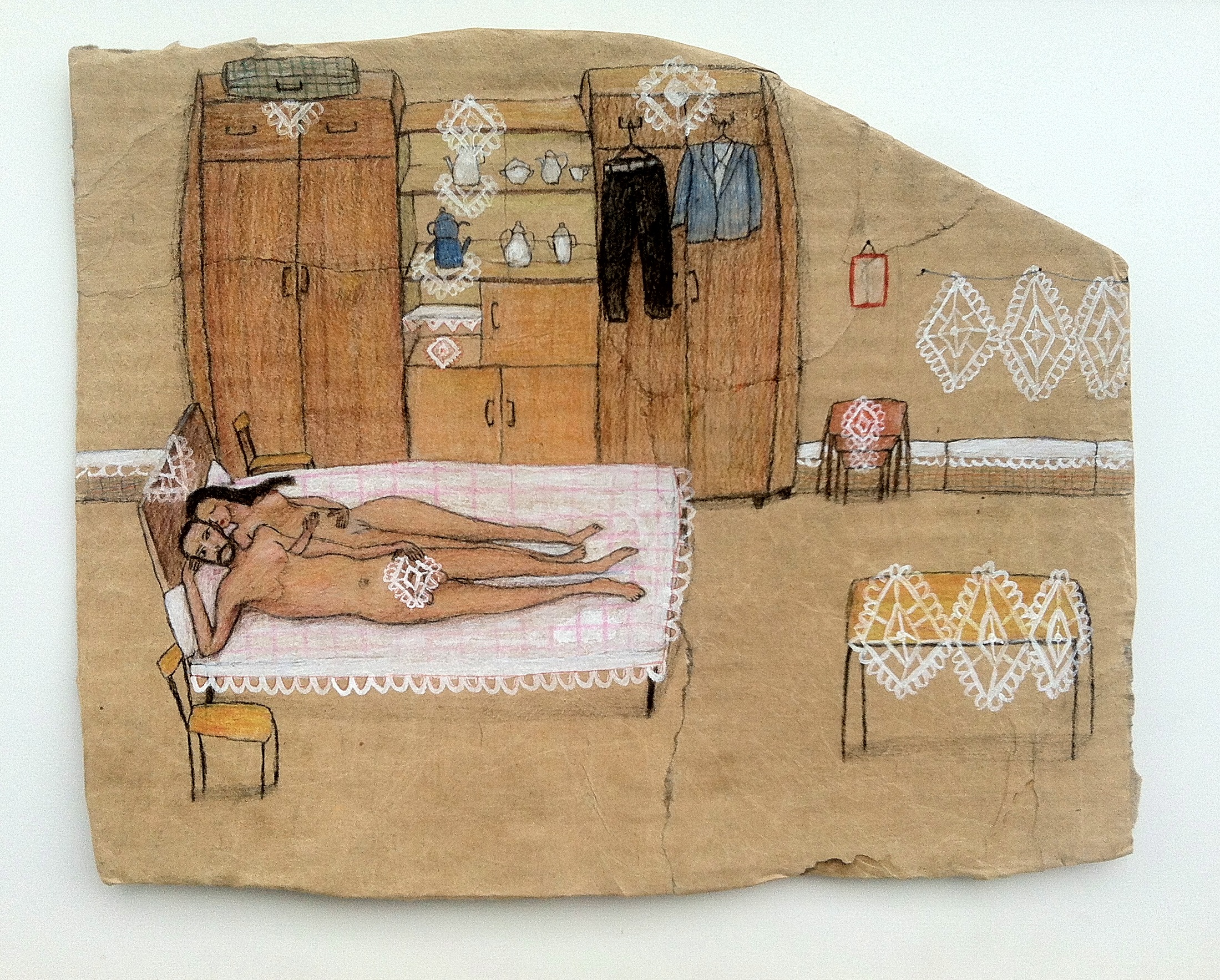

In August last year, Artan Hajrullahu presented his works in the exhibition “Artists in Quarantine,” a collection of artists’ works created during lockdown that depicted life in the pandemic. It suited the painter from Gjilan to a tee; most of his drawings, even beforehand, contained elements of everyday life, mainly inside the living room or bedroom.

Using familiar Kosovar household objects that he grew up with, such as handmade laceworks, mirrors and a wood burning stove, he explores human intimacy and tries to break social taboos. With a deep nostalgia for the wood burning stove that was present throughout his childhood, in his painting and drawings he conveys the warmth and togetherness that people found when they gathered in the room where the stove was. Whereas by placing handmade laces onto the naked bodies of his characters, he somehow seems to mock the refusal of Kosovar society to accept intimacy for what it is: part of daily life.

The total lockdown resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic didn’t pose any problems for Hajrullahu in terms of finding the materials necessary for his works. For years now he has drawn on pieces of cardboard that are usually thrown away by others. The “frame” of his drawings is often the shape of the cardboard pieces that he finds, many of which are from his time as a student. Even during his childhood, he used to paint on any piece of paper he could find.

His minimalist drawings with few elements are “unsettled” on the pieces of cardboard.

“Finding thrown away materials that you don’t need to spend money on has given me space for creativity; I can create anywhere,” he says.

Photo: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0.

Born in 1979, Hajrullahu finished painting studies at the Academy of Arts in Prishtina. Now, besides painting and drawing, he teaches students at the Visual Arts High School in Gjilan. For more than a decade, he has exhibited his work in group exhibitions in galleries and cultural centers in various countries around the world, from the U.S. and Germany to Croatia and Slovenia. He has also presented a range of solo exhibitions, including at the National Historical Museum in Tirana in 2006 and the National Gallery of Kosovo in 2010.

K2.0 talked to Hajrullahu about the form and content of his drawings, the wood burning stove and the mirror, about marriage and the laceworks, the living room as the epicenter of the family, and about the cold, and sex.

K2.0: How much did the economic circumstances of Kosovar families, especially during the ’90s and 2000s, when most of them lived in poverty, affect your selection of drawing materials? It seems that choosing to draw on cardboard is a form of saving, when we know that canvas is much more expensive, and also the frames and colors.

Artan Hajrullahu: I tried to think of something monumental and from there to move on to something minimal. If you start on a piece of paper or in a notebook, you cannot move on to something different. I was forced, if I may say so, to give shape to recycled [thrown away] materials and to have a space to draw there. A minimal one. This gave me the opportunity to think, or forced me to think, “What’s beyond this?”

There’s a moment when you can afford to buy material for academic work. For college assignment, the family initially helps you financially — to buy the canvas and the colors. But, there comes a time when economic crisis sets in. If as an artist you think that [with the beginning of economic hardship] everything ends there, then you will never accomplish anything.

This is exactly the point when you should start thinking “What next?” or “How can you find yourself?” Finding thrown away materials that you do not need to spend money on gave me space for creativity — I could create anywhere. And then, at a certain point, it became a habit to draw on pieces of cardboard.

Beyond the form, even the content and the expression of your drawings are more or less minimalist; all the characters gathered around the stove, drying their hair, all the family staying in one room, and similar details. What influenced the different elements?

This is a nostalgia about the household objects I grew up with. Each object reminds me of a story, and that story always relates to another story, and here begins the stimulus that then turns into an expression. My parents are also part of my drawings, but they represent a relationship from the past, even though I have drawn or painted them now. I don’t know, maybe it’s an emotion from the past, a way of trying to understand how they raised us!

The content of your drawings is not “glamorous” and it reminds me, above all, of the drawing in which you depict Migjen. You drew the poet on a piece of cardboard, naked, near a stove, with a small penis, and not in those “Napoleon poses.”

It has always bothered me how nudes are seen in our country, especially if they are related to national figures. Sometimes you start thinking, and you say, “wait, Migjen also took baths.” We can undress him, and see him like that. This doesn’t mean that we are stripping him of what he represents or what Migjen was, but the important thing is that we can see him in different ways.

This is crucial to my work. Everyone approaches a story differently and gets interested in something more personal; it’s the same area but the experiences are different.

This leads me to another question. There is always a wood burning stove in your paintings. Why?

Every family in Kosovo had a wood burning stove. For me, it represents my childhood, and even later years. We kept warm around the stove, cooked, got dry, and it smoked our room… it had many functions. The stove was always the epicenter of the family, and in a way all the socialization revolved around it.

Even in recent days, people have begun to adopt the wood burning stove in order to install the central heating around it. They don’t want to remove the stove, even though the heating system has changed; the stove still remains there.

During the winter, all the family and even the guests gathered in the room where the stove was. Children, the elderly, or those who had poor health slept there. People ate and had conversations there. The room with the wood burning stove symbolized family unification. You would freeze if you left that room. It was always crowded.

I’ve also seen some drawings of yours that seemed different from what we usually see from you; there were also drawings that depicted two perspectives.

Through painting one always tries to see something more. It is important to see what is hidden behind the other side of the painting. This is maybe a tendency to satisfy the curiosity about what is hidden behind it.

An example from everyday life: When you pass someone, often you turn your head to see behind them. Always prejudicing against an individual or society, creating unnecessary stereotypes in the society or circle where you live; always thinking what it could be and how it looks from behind.

It is a curiosity and imaginary impression, where we as individuals and society want to arrive. And beyond the imaginary, we can see and feel with our senses [something] that before was maybe very relative.

What caught my attention in your nudist drawings is that around a couple of the characters you draw lacework or the wood burning stove. Why?

Metaphorically, the lacework represents marriage, the unnecessary embellishment of life, aesthetics, among other things, even the spiritual. When a couple got married, the bride would bring the çejz [dowry] that she had worked on for a long time before the marriage. On the wedding day, she would present it and show her handwork to others. This is the same as when artists exhibit their work and want to show something unique.

Another thing that motivated me to draw nudes is the fact that in private conversations people talk a lot about nudity or sex. But, when we need to speak publicly and treat it as a “topic,” then it gets silenced. There is a tendency to see it as shameful and immoral.

Nude drawings often contain references to family tradition and traditional themes, prejudices against nudity and social taboos. This came as a spontaneous artistic expression about our social reality and intimate processes. The mentality of our society is still judgmental and considers that we should not talk publicly about these relations. I’ve tried to use art to present the naturalness of human life and to access a familiar intimacy.

The characters in the world of my work are often naked and in need of something to warm them up. The wood burning stove is a metaphor of spiritual fulfillment, taken from our collective memory.

Image courtesy of Artan Hajrullahu’s personal archive.

The part where the bedroom is seen as a gallery is interesting. The work for the realization of an exhibition is done in the studio; the exhibition remains an exhibition. This approach makes me curious but also worries me. The bedroom to be more of a gallery than a creative studio? I also remember another drawing where you depict a couple laying in the bed and the man has his penis covered with lacework.

In most of the cases, for both a woman or a man, it is as if the moment when they get married means “enough.” “It ends here, now get on with the family,” they say. We are taught that family is sacred, but you should never give up the aspirations you had for the future.

In the drawing you mentioned, there is a newlywed couple on their first night of marriage. They are naked but unable to enjoy each other. It is precisely the excessive aestheticization of life that has snatched life from the simple pleasures of being together with someone. Here, the laceworks are aesthetic and spiritual covers that show a lot of personal ambition and do not allow us to see things as they are.

Something else that impressed me in your work is the “erasure” of objects’ dimensions; the wood burning is further away but looks bigger than the other objects that are nearer. One cannot know where the surface is and where the wall is. What does this mean?

I will tell you a story. I was hanging out with a friend who is an architect and he said to me, “Artan, you don’t use perspective anywhere.” Perspective in this case means that the object that is nearer should be bigger than the one that is further away. But for me, it is all a kind of illusion.

I use the elements or objects in a naive, childish way. It could be empty in terms of dimensions, but perhaps it is a better way to express the emotions. I think it is important to experience things differently.

We cannot forget the mirror in your drawings and paintings. We almost see it as often as the wood burning stove. Most of the human figures in your drawings face a mirror somewhere. Why?

In front of a mirror, you somehow always feel a form of complacency. Beyond the self-satisfaction there you can see many things, or create a lot of ideas and characters, that may not be true.

In my self-portrait, I’m a bit muscular, even though in reality I’m not. But, maybe that’s how I see myself in front of the mirror; somehow in front of a mirror we project ourselves as muscular, but it does not mean that it is so.

Or it could be another reality, but that remains a reality. When you see in my drawings a girl drying her hair, or near a wood burning stove, she can be seen as just a girl in front of the stove. But, when you see her in front of the mirror you can say, “Wait, is there something else?” You can wonder if there is something beyond; whether she is someone else?K

Feature image: Atdhe Mulla / K2.0.