Located near Rruga B in what was once a Prishtina suburb but which is increasingly part of the urban center, a socialist building holds a treasure trove of documents that tell Kosovo’s history. Employees wearing white coats, goggles, dust masks and gloves move through the corridors and offices.

Behind two glass doors is Kosovo’s Archive, officially known as the State Agency of Archives of Kosovo.

The documents preserved here date back to 1437 (a page from an Arabic-Persian dictionary). There’s an Ottoman document from 1608 as well as verdicts, records and diplomas from the period after the Second World War up until the present day. Documents related to the Constitution of Kosovo and personal documents issued by state institutions are also preserved there.

The passing years have left their mark on the archive. The staircase and the wooden bannister that snakes up the building’s four floors is noticeably worn down.

The names of several offices and halls have remained unchanged since the archive first opened its doors on May 25, 1977.

In the same year, the Rilindja newspaper wrote about the opening of the 7,200 square meter archive, featuring a laboratory for the conservation, microphotography, restoration and lamination of damaged documents. There was also a bookbinding and off-set printing press, a symposium hall and an exhibition hall. The Rilindja article also mentions historian Ismet Dërmaku, who was the archive’s first director and who published the book “Kosovo Archive” in 1977.

Founded in 1948 as the Archival Center, in 1951 it became the Kosovo State Provincial Archives. While the building was originally dedicated to housing archives, today it is also home to the Kosovo Cadastral Agency.

Repositories at the mercy of fate

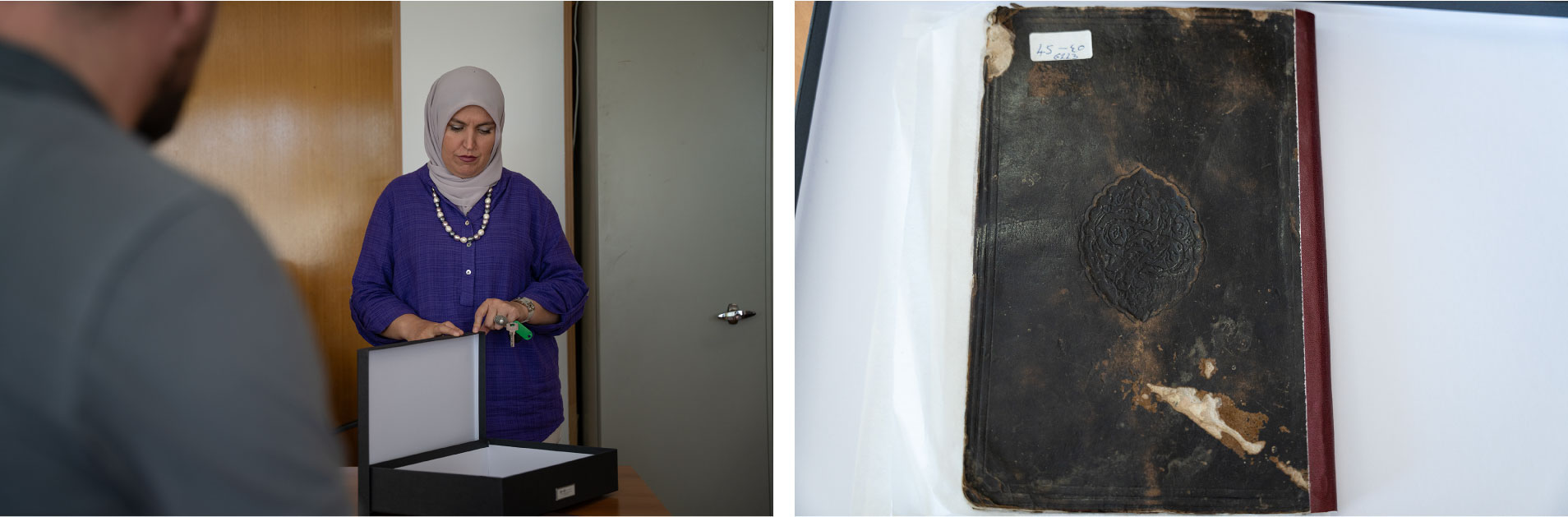

Zelije Shala is the head of the Treasury Division, also known as the archive repository. Although Shala did not know Drëmaku, she said that they continue his work.

“It is thanks to him that we have this museum, many of the investments from that time still serve us today,” said Shala, accompanied by repository worker Nexhat Sertolli. According to their calculations, there are 4.5 linear kilometers of documents in the archive.

Zelije Shala stands in the lobby of the archive repository, while in the background is the “super-secret” room. Photo: Majlinda Hoxha / K2.0.

Before the documents arrive at the archive, they pass through various hands. Institutions are required to submit files to the archives after 30 years at the latest. In addition to files from state institutions, the archive also holds personal files that have been voluntarily submitted. The files that arrive at the archive are first sorted by year into files or boxes, then stored alphabetically.

The archived documents are not preserved in adequate conditions. As the employees move through the narrow space between paper-stacked shelves they disturb the layers of dust. The cleaners don’t come regularly and don’t have the right cleaning equipment. Since 2020, dust has gathered freely as the doors on each floor were removed to make way for new doors, which never arrived.

Three years ago, a “super-secret” room was built with security shutters and an alarm system to store important state documents. There are no secrets currently in the room because the room is empty.

Most of the shelves are old and take up a lot of space. The new shelves are mounted on rails and are more space-efficient. The newly installed lights have white LED bulbs which are harsh on the eyes and cause documents to fade.

“The lights should be special,” said Shala. “They shouldn’t be this strong as it fades old documents. Now, when we open up a shelf to organize or repair it, sometimes it stays open for up to an hour. This is how the documents fade, it has happened several times.”

When the archive was first built it had a temperature control system and a ventilation system. For documents to be preserved the temperature should be kept between 18 and 21 degrees, regardless of the outside temperature. However, the old climate control system was dismantled two years ago and has not been replaced.

“In the summer we rush to open the doors and windows to cool the space a little. In the winter, we turn on the heating on each floor, which warms the space a little, but it is difficult,” said Sertolli, who wears a white coat with the archive’s logo while shrugging his shoulders.

Nexhat Sertolli opening one of the new archive lockers. Photo: Majlinda Hoxha / K2.0.

While walking through the floodlit basement, Shala said that one winter the stairs were covered in ice, causing her to slip and injure herself. Flame-resistant gloves can be found throughout the archive, labeled in Serbian: “U slučaju požara. Povući” [In case of fire. Pull out]. In the 46 years since they were installed, they have never been needed.

“We have the old fire safety system, but they also installed a new one,” said Sertolli. When asked if it works, he replied, “Yes… I believe so.”

“Have you ever tried it?” Shala asked and they both laughed.

Local, Yugoslav and world newspapers, such as the French newspaper “Le Monde” from the 1950s, are carefully preserved in a small room. Two heavy duty lockers designed to protect documents from radioactive attacks stand behind the newspapers. One of them contains the work file for the Constitution of Kosovo. Sertolli tries to open it, but fails. Age and humidity has caused the gears to jam.

“It’s jammed and the key doesn’t work, it has been like this for some time now. Look, it’s still not opening,” he said, trying to open the heavy door again.

The Rilindja newspaper is archived in the basement of the Kosovo Archive. Photo: Majlinda Hoxha / K2.0.

Sertolli and Shala were organizing a pile of documents alphabetically. They don’t have a processing room, so they improvise on a table surrounded by lockers.

There’s milk in every office

Shkurta Rrustemi, responsible for organizing materials submitted for archiving, is seated in her office wearing a mask and plastic gloves. She sorts through the documents, setting aside expired ones such as certificates with a six-month validity. Those that need to be archived, she stamps and classifies.

“The daily processing rate is five centimeters of stacked documents. This is always achieved and regularly exceeded,” said Raba Kelmendi, who is the head of the Archival Material Regulation Division.

After removing her mask, Rrustemi said that the documents they receive are often in poor condition.

“They are very dusty, some of them have different smells, since we don’t know where they keep them. It is necessary to keep our masks on, otherwise we inhale the dust,” she flips through the documents while speaking, revealing that today’s documents were in noticeably better condition than normal.

Shkurta Rrustemi (left) and Raba Kelmendi (right) arranging the archival material. Photo: Majlinda Hoxha / K2.0.

There are milk cartons in every office in the archive.

“We drink milk because of the dangerous chemicals, perhaps it protects us a little,” said Hazbije Krasniqi, who heads the Protection Division. On the work desk, there are documents that appear beyond repair. But, by using cleaning methods involving potent chemicals, Krasniqi, a former biology professor, manages to restore them.

“I came here in 2006. If I had known that I would end up here, maybe I wouldn’t have come. But now I’m connected to this place. I am connected to the documents which we protect and save. They can have great importance for someone,” she said. In addition to historians who visit the archives to track down documents, members of the public come to find documents. This includes proof of work history for a pension, evidence of Yugoslav property compensation as well as enthusiasts who collect newspapers.

Krasniqi takes a document to clean. She dusts it, wipes it with a sponge, then inspects the document and cleans it with a special eraser. Each stage rejuvenates the document a little further. In some places, the old paper is bleached due to the cleaning process.

Hazbije Krasniqi preserving damaged documents. Photo: Majlinda Hoxha / K2.0.

“Then we disinfect the document with alcohol, but we have to patch test it first to see if it changes the color,” she said, as she tries it on the end of a signature and sees that the color changes. She avoids the signature and continues to clean the rest.

Over time, paper deteriorates and so it is often preserved through a lamination process.

No special treatment for the archive’s oldest document

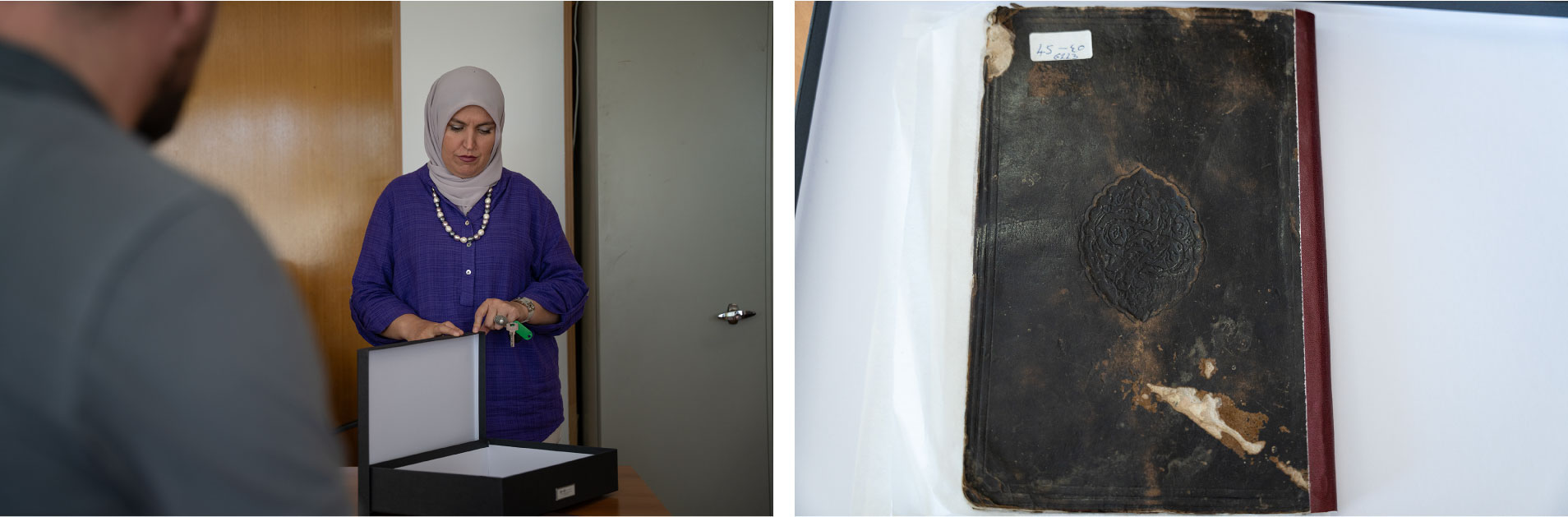

Before 2010, an endowment deed from Mehmed Pasha Kaçanik dating from 1608 was found hidden among a pile of papers. Mehmed Pasha was the son of Koca Sinan Pasha, who served as the grand vizier of the Ottoman Empire five times. This is the oldest document preserved in the Archive of Kosovo.

A researcher discovered the deed while conducting research in the archives. It is suspected to have ended up there along with many other documents during the document collection campaigns prior to the last war in Kosovo.

Ottomanologist Hatixhe Ahmedi presents the 415-year-old document. After placing it on the table, she keeps a hand on it, almost as if she’s reluctant to part with it. After a while, she opens it up, saying that the fresh air is good for it.

Hatixhe Ahmedi opened the folder that contains the oldest document in the Kosovo Archive. Photo: Majlinda Hoxha / K2.0.

The endowment deed is written in Ottoman Turkish, using the Arabic alphabet. This document details the “awqaf” or endowments made by the Albanian Pasha. Evidence of these endowments can be found from Kaçanik to Dibër and Ohrid.

The pages are encased in a leather cover and have become fragile over the years. The pages are intricately written, but a white piece of paper bearing a reference number is glued to the document.

“It shouldn’t have been done, but it was. We don’t dare to remove it because it might get damaged. I don’t know who did it,” said Ahmedi, also pointing out that a previous restoration and conservation attempt on the document was not done properly.

A reference tag is also attached to the page from the Arabic-Persian dictionary. On the small 500-year-old page, the reference number written on paper from this century looks out of place.

“I don’t know who glued it there,” shrugged Shkëndije Hakaj, the archive official responsible for the library that preserves nearly 13,000 titles.

She picks up a book from 1572, written by Muhamet Ali El Bergin, with a cover decorated with gold. It is rarely opened and not displayed publicly since the archive cannot control exposure to humidity or temperature.

Shkëndije Hakaj, while showing two other century-old assets from Kosovo’s Archive. Photo: Majlinda Hoxha / K2.0

The Kosovo Archive functions within the Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sports, but does not have the necessary institutional attention.

The archive currently has too few employees. Including the seven inter-municipal archives, there are 105 employees. Sixteen workers have retired and their positions have not been filled. The archive’s employees said that in order to properly organize all the material they would need another 150 workers.

The digitization of the archives would avoid damage from handling and environmental conditions. The digitization process has been underway for almost 10 years, but progress is slow as it is carried out by two employees who also have other duties.

Digitization Officer Bekim Aliu has a lot of equipment in his office. A computer, document digitizer, microfilm digitizer, an old 16mm film camera and piles of old documents waiting to be digitized.

A small room inside the office holds 25 kilometers of micro-film containing around one million documents. Aliu opens one of them that contains documents about Kosovo from the U.S.

“I opened this because I processed it and it stayed here for three days. It should stay outside for a while to get used to the new temperature conditions. Otherwise, if we open it right away, it may break because the films get strained,” said Aliu, who entered the microfilm room, pushing aside some items to free up space.

Bekim Aliu wanders from one computer to another in the process of digitizing the archives. Photo: Majlinda Hoxha / K2.0.

Aliu knows that digitization should be handled differently, as he has seen it done in other countries.

“In Turkey there is a whole institute that deals with digitization. We have a system for digitization but we are only two people. Many countries digitize their archives using external companies and we hope to do the same,” said Aliu.

The archive faces other problems that make work difficult. For some time, the archive has not had a prosecution official and the employees are afraid that they will continue to be neglected by the ministry.

Feature Image: Majlinda Hoxha / K2.0.