"Sometimes, the border meant death, because the guards were allowed to shoot anyone in their line of sight."

"I wanted to escape because I was driven by the desire for a better life awaiting us on the other side, where I wouldn’t have to lie to my child."

"Right there, sitting on that stone, was the last time I ever saw her."

"I had to learn freedom again from scratch, insofar as a former convict in an enslaved country can be free."

"There are things I simply don’t want to remember because the pain is blinding."

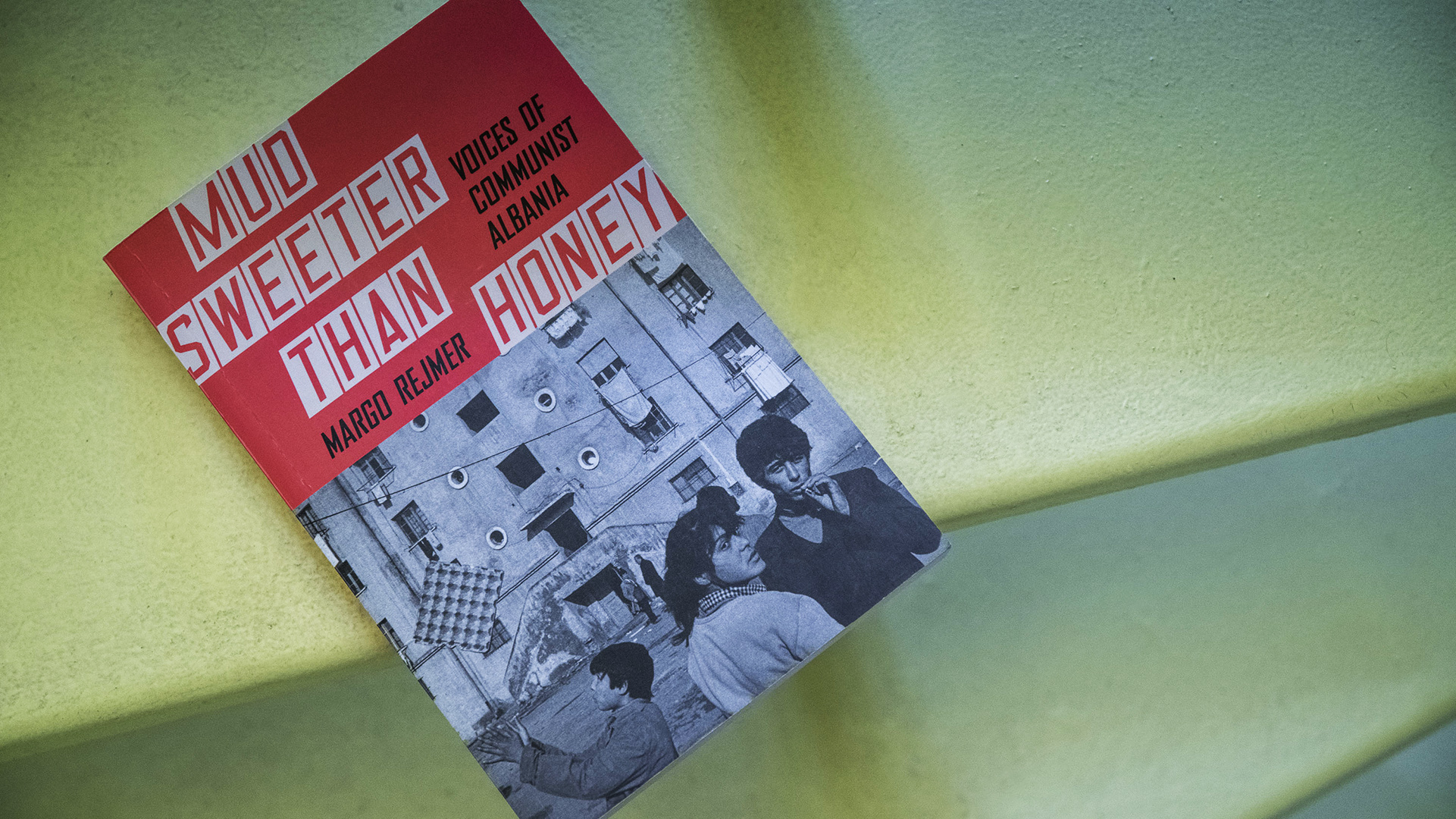

Margo Rejmer

Małgorzata (Margo) Rejmer is an award-winning Polish novelist, reporter, and writer of short stories. She is the author of the novel Toximia and the nonfiction work Bucharest: Dust and Blood. In 2018 she was awarded the Polityka Passport, the most prestigious prize in Poland for emerging artists, for Mud Sweeter than Honey. Her books have been translated into eight languages. She lives in Warsaw and Tirana.

DISCLAIMERThe views of the writer do not necessarily reflect the views of Kosovo 2.0.

This story was originally written in English.