Brussels based talks are a ‘Dialogue of the Deaf’

The EU-mediated negotiations between Kosovo and Serbia have become obstructed. How can they progress in 2017?

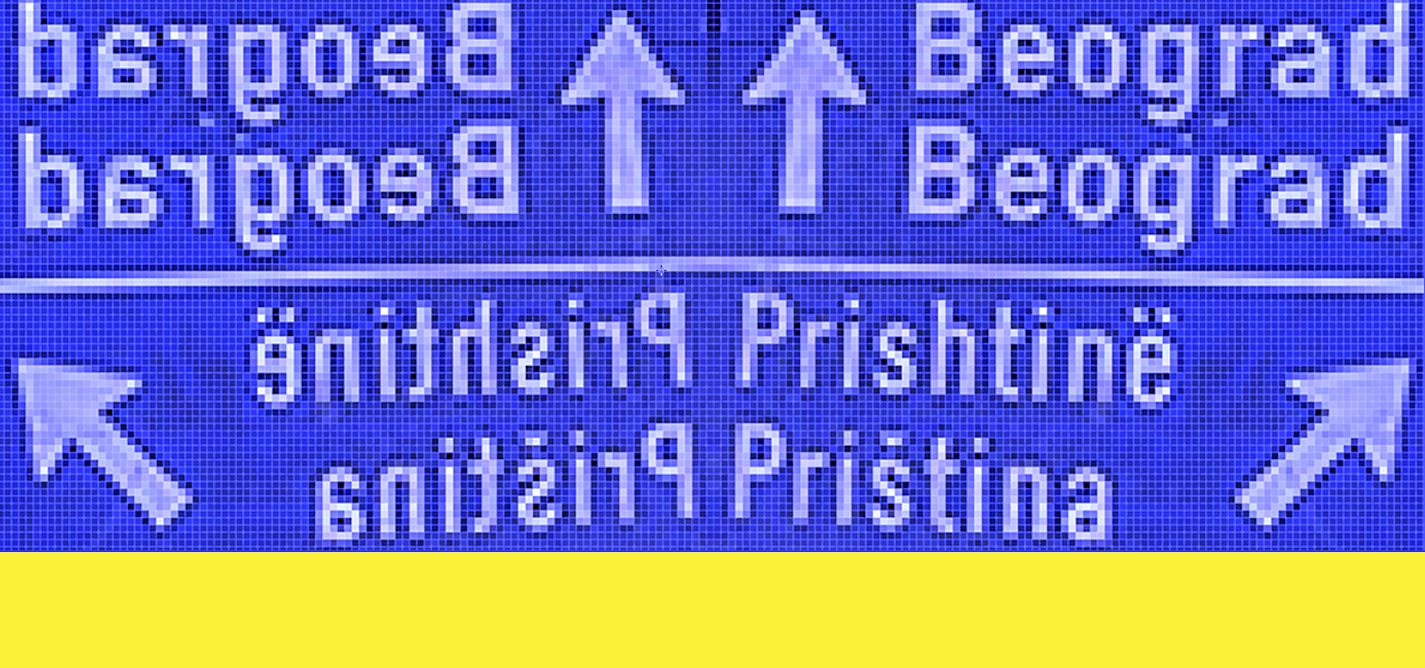

The irony of this whole situation is that in their essence, bridges, just like trains, are symbols of communication.

Ignoring the bitter realities on the ground could undermine Brussels’ role in the negotiation process.

The EU’s mediation strategy of constructive ambiguity is proving itself to have destructive effects.

Miruna Troncota

Miruna Troncota is a young researcher based in Bucharest (Romania) specializing in the EU integration of the Western Balkans. She is a lecturer and postdoctoral researcher at the Department of International Relations and European Integration, at the National University of Political Studies and Public Administration, Bucharest. Her recent book is “The War of Meanings. Post-conflict Europeanization and the Challenges to EU Conditionality in Bosnia and Kosovo” (Tritonic Publishing House, 2016).

DISCLAIMERThe views of the writer do not necessarily reflect the views of Kosovo 2.0.

This story was originally written in English.